The revelation that some insurance beneficiaries -- particularly ones with terrible chronic illness -- will continue to pay large annual out-of-pocket costs next year is the best news conservatives have heard all day.

That's perhaps a slight exaggeration. But it's true that Obamacare opponents are putting on the same performance they stage every time we learn of an Affordable Care Act glitch: First, feign concern for the individuals impacted by the glitch, without mentioning that it's almost certainly a protection they don't support to begin with; then express disappointment that the law's "not ready for prime time," as Grover Norquist said on CSPAN this morning; then cite it -- whatever it is -- as evidence that the entire law should be repealed, defunded, delayed. Preferences may vary.

The latest news concerns a sliver of insured individuals and families whose plans employ separate administrators for medical and pharmaceutical benefits, and who currently face high out-of-pocket limits (copays, deductibles, etc.). Like all beneficiaries, they were supposed to enjoy a hard cap on annual out-of-pocket costs beginning next year. These particular folks will have to wait another year before that cap applies to their drug coverage. That's a big bummer -- a benefit deferred -- particularly for people with chronic illnesses. And it raises the question of why, exactly, insurance companies need more than three years to get this right, and why the administration should have provided them "transition relief."

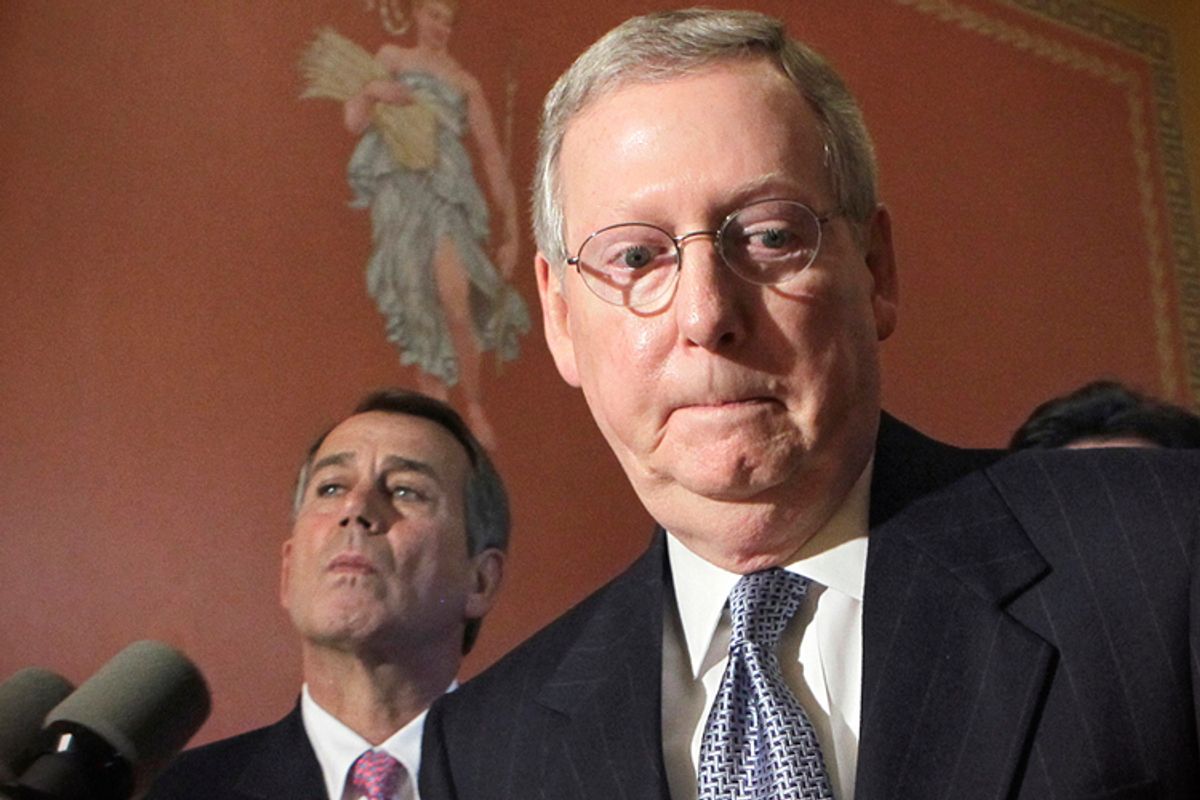

Speaker John Boehner's office cries crocodile tears: "The Obama administration announced another delay that protects big businesses from its health care law."

But as anyone who isn't singularly committed to destroying Obamacare tires of saying, this isn't evidence that Obamacare "isn't working."

The fact that the ACA is a very long statute is supposedly a damning indictment of the healthcare reform process and the law itself. But it's also a consequence of the fact that the ACA includes a lot of provisions peripheral to its central purpose of creating a functioning healthcare finance system for people who aren't currently insured. Setting aside everything else, Obamacare is a pretty straightforward system: First, create state-based insurance markets that pool beneficiaries. Second, using a system of carrots (subsidies) and sticks (penalties) make sure as many people as possible enter the marketplace. Third, regulate the marketplace so that the products are affordable and non-discriminatory.

This is the mandate/subsidize/regulate approach -- sometimes called Obamacare's three-legged-stool -- and if any one of the three legs breaks, then the whole system is in trouble. So it's not an invulnerable system. But that means there's a finite number of problems that could really threaten the program. The good news, in other words, is that it's pretty easy to identify the kinds of "glitches" that would actually endanger the law in advance. And armed with such a list, you'll be able to determine whether the latest warning of Obamacare's impending failure has merit, or whether you're being misled.

The Insurance Exchanges

The state-based marketplaces are the foundational elements of the ACA. Some of these are run by states. Some are jointly run by states and the feds. And many (particularly in red states) are federally administered. If they aren't functioning pretty well by Jan. 1, the law's in trouble. If some or all of the exchanges won't be fully operational, if federal subsidies aren't automatically reducing monthly premium payments, if insurance companies begin dropping out of the individual market in large numbers -- all of these would imperil the rollout of the law.

The Beneficiaries

Even if the marketplaces are functional and user-friendly, they still need users, and particularly they need an appropriate mix of young and old, healthy and sick consumers. This is why GOP calls to delay the law's individual mandate are a non-starter. If the White House were to administratively delay the mandate, that would be remove a key incentive for young, healthy people to enter the system, inviting a potential "adverse selection" problem, and then a death spiral of increasing premiums. Even with the mandate in place, if too many young people choose to pay the penalty rather than pay more money for an approved insurance plan, then the market will be overrepresented by high-risk beneficiaries, and premiums will rise anyhow. The administration believes they need about 35 percent of new beneficiaries to be between the ages of 18 and 35. If they're wide of that goal in the wrong direction insurance costs will increase for everyone else and more and more people might choose to drop out.

The Regulations

Some of the law's major regulations are already in effect, and working fine. Others, like the employer mandate, have been delayed for a year. (That was a costly, consequential but nonexistential glitch, and the "best" Obamacare foes are likely to get.) The regulations that really matter won't really have any impact on consumers until Jan. 1, and it's probably too late to delay them. But if for any reasons, under any justifications, insurance companies were to be given a reprieve from any of the following, the law would cease to function as intended.

1) Guaranteed issue: The requirement that insurance companies sell coverage to all consumers, even ones with medical conditions.

2) Community rating: The "pooling" function, which requires insurers to charge all similar beneficiaries in their markets the same prices, regardless of health status. Without it, people with preexisting conditions would be priced out of the system.

3) Age rating: The ACA forbids insurers from charging older beneficiaries more than three times what they charge younger beneficiaries. This is why, relative to need, premiums will be higher for young people than for old people, but without this requirement, insurance would be too expensive for older uninsured people and they'd remain priced out of the system.

4) Risk adjustment: Obamacare contains a number of provisions intended to create incentives against, or to correct for, uneven risk distribution in the marketplaces. States set these rules in some cases, the feds in others, but they're intended to prevent cherry picking by insurers and penalize plans that attempt to cherry pick healthy beneficiaries at the expense of plans that don't.

5) Gender rating ban: The ACA requires insurers to equalize treatment of male and female beneficiaries. It bans them from engaging in what's known as "gender rating" -- charging women higher premiums because their health costs typically exceed men's. This is perhaps the law's single most consequential provision (though I hesitate to call it a "benefit") for currently uninsured female beneficiaries. And though the marketplaces might technically be able to function without it, a delay would leave women and men on unequal footing, in a very visible way, and badly undermine political support for the law.

That's at least a partial list. If any Obamacare stories in the coming weeks touch on these issues, the law's critics and supporters alike will be right to issue dire warnings. Otherwise you can safely assume the noises you're hearing are conservatives behaving opportunistically.

Shares