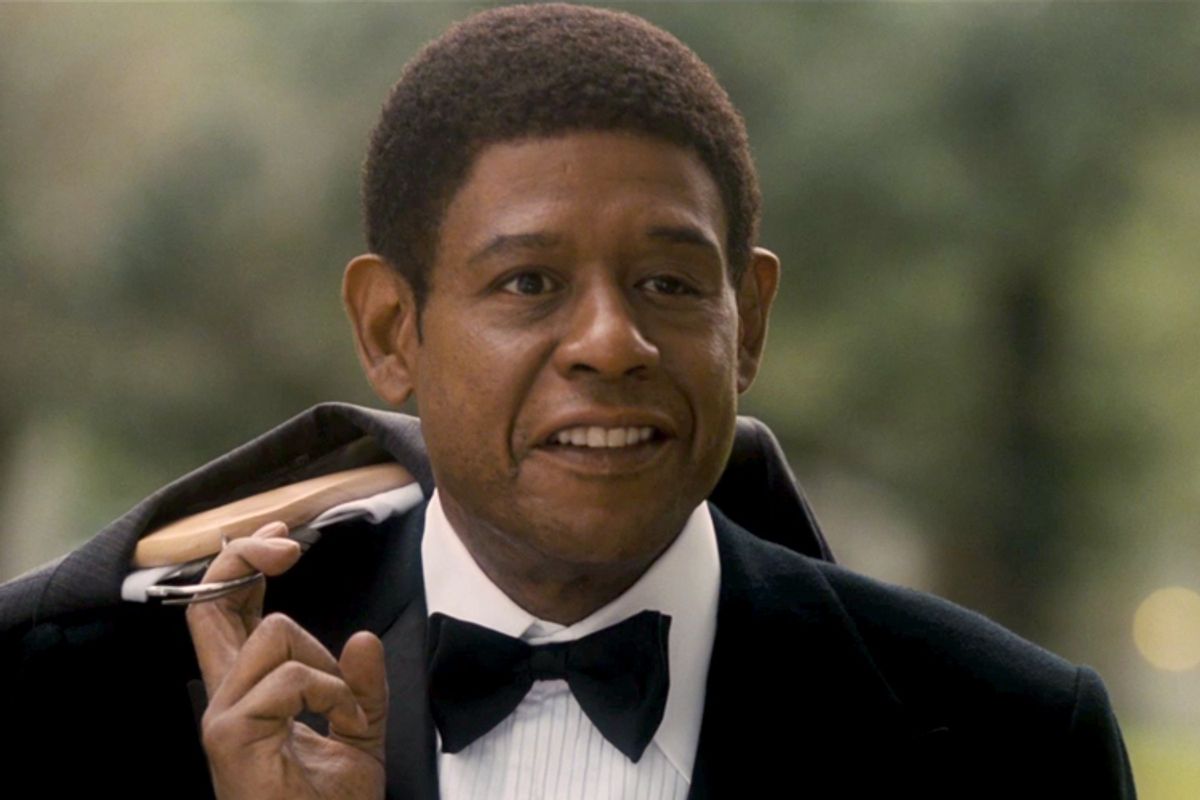

There’s a scene about midway through “Lee Daniels’ The Butler” – an ungainly title for an ungainly picture – that captures many of the movie’s contradictions, and its surprising power. It’s 1968, and Martin Luther King Jr. (Nelsan Ellis) is discussing the Vietnam War with some of his closest aides and friends. “How many of your parents support the war?” he asks this group of African-American men. Almost all of them raise their hands. King then asks Louis Gaines (David Oyelowo), a young man sitting next to him, what his father does for a living. “My father’s a butler,” Louis says, not without embarrassment. He doesn’t tell King that his father, Cecil Gaines (Forest Whitaker), is a butler at the White House, and was almost certainly in the room during King’s historic meeting with Lyndon B. Johnson in the Oval Office.

Black domestic workers, King tells Louis, have played an important role in the struggle for civil rights. At first Louis assumes this is meant as mockery, but King presses on. Maids, butlers, nannies and other domestics have defied racist stereotypes by being trustworthy, hardworking and loyal, King says; in maintaining other people’s households and raising other people’s children, they have gradually broken down hardened and hateful attitudes. Their apparent subservience is also quietly subversive. This poignant and humbling recognition of the sacrifices made by millions of African-Americans who appeared to have no voice is an important turning point for Louis, in his consideration of his father’s life, but it also captures King’s extraordinary philosophical depth in a few moments. In case there isn't enough going on in that scene, let us note that it takes place in the Lorraine Motel in Memphis. Minutes or hours later, the great civil rights leader will step outside onto the balcony and be shot dead.

I’d be hard-pressed to describe “Lee Daniels’ The Butler” as a good movie. It’s programmatic, didactic and shamelessly melodramatic. (Danny Strong’s screenplay is best viewed as fictional, although it’s loosely based on the true story of longtime White House butler Eugene Allen, who died in 2010.) Characters constantly have expository conversations built around historical markers, from the murder of Emmett Till to the Voting Rights Act. Every time Cecil serves coffee in the Oval Office, he stumbles upon epoch-making moments: Dwight Eisenhower (Robin Williams) debating whether to send federal troops to desegregate the schools in Little Rock; Richard Nixon (John Cusack) plotting a black entrepreneurship program to undercut the Black Panthers; or Ronald Reagan (Alan Rickman) telling Republican senators he plans to defy Congress and veto sanctions against South Africa. Cecil and Louis, the warring father and son played by Whitaker and Oyelowo, might as well come with labels: Cecil is following in the footsteps of Booker T. Washington; Louis in those of W.E.B. Du Bois.

But “The Butler” is indisputably an important film and a necessary one, arriving at the end of the summer of Paula Deen and George Zimmerman and the Detroit bankruptcy, a summer that has vividly reminded us that if America’s ancient racial wounds have faded somewhat, they have never healed. For a black filmmaker to tell this fraught and complicated story now, in a mainstream picture with an all-star cast, is significant all on its own. Faulkner’s observation that the past is never dead and isn’t even past has come to sound trite through endless repetition by politicians and journalists, but it speaks to our country in 2013, and to the impact of this movie. And before I wander too far afield, “The Butler” is also a showcase for numerous terrific black actors, including Whitaker, Oyelowo, Terrence Howard, Cuba Gooding Jr. and Lenny Kravitz, not to mention a fiery and sure-to-be-Oscar-nominated supporting role for Oprah Winfrey as Cecil’s wife, Gloria.

For someone of my generation, the civil rights movement may seem like an overly familiar pop-culture topic. But it’s been more than 20 years since “Malcolm X,” “Mississippi Burning” and “The Long Walk Home,” and closer to 40 years since groundbreaking TV specials like “The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman” or the miniseries “King.” Much of the sweep of history in “The Butler,” which begins in the Jim Crow Deep South of the 1920s and ends with a black man in the White House, may seem like a dim, black-and-white flicker to many younger Americans.

Daniels, previously the director of “Precious” and “The Paperboy” (forever famous as the movie in which Nicole Kidman pees all over Zac Efron), may not be a subtle storyteller, but he delivers big, emotional moments with considerable force. He makes the impact of the Kennedy and King assassinations seem real and present by focusing on individuals and details – Cecil, trying to comfort a sobbing, blood-spattered Jackie Kennedy (Minka Kelly) – and his re-creation of the Woolworth lunch counter sit-ins of 1960, or the Birmingham street scenes when dogs and fire hoses were turned on marchers, possess a startling violence and freshness. In a time when a dominant current in American conservatism is dedicated to erasing both history and science, to insisting that “there are no lessons in the past,” it’s useful to be reminded how much about contemporary American life is shaped and conditioned by those events.

Daniels performs another public service by turning the well-meaning condescension of “The Help” upside down and telling the story of a black domestic worker and his family entirely from their point of view, with minor supporting characters that include five United States presidents. (Cecil also served under Gerald Ford and Jimmy Carter, but they’re only seen in news footage.) The parade of famous white actors playing White House occupants is bizarre and almost arbitrary – Cusack looks nothing like Nixon, although James Marsden is well cast as JFK and Liev Schreiber makes a surprisingly good Johnson – but that’s a sideshow attraction. (Daniels understands precisely how he’s twisting the knife with Jane Fonda’s cameo as Nancy Reagan, by the way.) The main event is a terrific cast of African-American principals, headlined by the immensely dignified performance of Whitaker, playing a man who has raised himself by his own wits and almost Nietzschean willpower from the brutal cotton fields of Georgia to the corridors of power.

As a boy, Cecil witnesses his mother raped and his father murdered by a white overseer, and that’s the background his son – raised in the polite, formal segregation of 1950s Washington – can never understand. Then the overseer’s guilt-ridden mother (Vanessa Redgrave) takes Cecil in and trains him as a “house nigger,” a polite, well-dressed automaton who is almost invisible and virtually silent. (I quote that offensive expression because it’s important and recurs several times.) The instruction delivered to Cecil over and over, including at the White House, is that he sees and hears nothing, and that a room should feel empty when he is in it. Whatever Daniels’ flaws as a filmmaker may be, in all his movies he’s acutely sensitive to the possibilities of human communication, even in impossible situations. Redgrave’s character clearly feels for Cecil and gives him what little she can; in her own way, she too is a victim of the system that has destroyed his family.

Over the years, Cecil makes his way from Georgia to North Carolina to a luxury hotel in Washington and finally to the segregated service staff of the White House. (Implausibly enough, it was Ronald Reagan, a font of old-school racist policy and personal generosity, who finally insisted on equal treatment for black employees.) He learns the intricacies of wine and whiskey, builds up an autodidact’s vocabulary and masters the fine art of being charming without appearing confrontational. Every black person in this line of work (Cecil observes in voice-over) has two faces, of necessity – one for his white employers and clientele, one for his family and friends. Whitaker plays Cecil as a man making a long, lonely trek uphill with a heavy load on his back, and the film’s other black characters all deal with life under a racist system in their own way.

Cecil’s friend Howard (Terrence Howard) is a good-time Charlie and numbers runner; Cecil's colleagues at the White House include foulmouthed ladies’ man Carter (Gooding) and educated, upward-bound James (Kravitz). I suppose Winfrey is customarily too busy playing her own public persona to play dramatic roles, but she’s damn good at it; the proud, angry, boozing, cheating and ultimately ferociously loyal Gloria has a vivid and very non-Oprah reality about her. If Daniels and screenwriter Danny Strong intend the tension between Cecil’s bootstraps assimilationism and Louis’ Freedom Rider-turned-Panther radicalism to be the movie’s central driving force, it doesn’t quite work. In a picture driven by a vibrant portrayal of African-American life and the visceral, explosive force of history, their opposed and intersecting character arcs feel overly constructed.

Daniels’ point, of course, echoes what King tells Louis: The traditions of Du Bois and Washington, of self-sacrifice and hard work on one hand, and street protest and political organizing on the other, are not as distinct or disconnected as they may appear. Both have driven a history that isn’t finished yet. While the election of Barack Obama serves as the culmination of this story -- and for African-Americans of Cecil Gaines’ generation it was an unimaginable, even millennial victory – in the larger story of America it was an unexpected plot twist whose true consequences remain unknown. One hundred and fifty years ago, Abraham Lincoln asked whether a country conceived in liberty and dedicated to equality would work out, and we still don’t know. “Lee Daniels’ The Butler” is big, brave, crude and contradictory, very bad in places and very good in others, and every American should see it.

Shares