No mayor in 50 years has overseen as many physical changes to New York City as Michael Bloomberg. From Cornell's Roosevelt Island Campus to Brooklyn's Atlantic Yards and the Second Avenue Subway, development projects begun under Bloomberg will be shaping the face of New York for decades to come. His influence was beautifully illustrated by a recent New York Times graphic series, "Reshaping New York," which ticked off the best of the boom, the many neighborhoods that could not, after 12 years, recognize themselves in the mirror: Hunter's Point, West Chelsea, Williamsburg, Downtown Brooklyn.

Coney Island, where Bloomberg fought one of his toughest and most expensive land use battles, was missing from that commemoration. The plan to rezone the famous beach resort was, as the mayor remarked in 2007, "one of the largest and most ambitious rezonings we've proposed for Brooklyn." By the time the bill passed the city council two years later it had become more transformative still, shrinking the outdoor amusement area from 40 acres to nine.

But unless you know Coney Island and the story of the remarkable land dealing that has occurred there, this can be hard to see. The New Coney Island -- a year-round destination anchored by franchise restaurants, shops, and condominiums -- is only just emerging.

When it does, it will be the perfect monument to Bloomberg's divisive decade of rezoning for development, cheered by some and mourned by others. Land values in Coney Island skyrocketed when the administration made rezoning a priority. Franchises like Applebee's and It'Sugar have since arrived. A new theme park, built by Zamperla, which also makes rides for Six Flags and Disney, was constructed in 100 days and has entertained hundreds of thousands of New Yorkers. There's Starbucks coffee available, and salads. For better or worse, Coney Island has begun to look more like everywhere else.

This was once a singular place, an amusement park so grand and unusual that on an average weekend in its heyday, visitors mailed a quarter-million postcards to friends and relatives. Luna Park, the flagship attraction that burned down in 1916, drew nearly 100,000 attendees each day. By the time the subway reached Stillwell Avenue, in 1918, the area drew still more visitors. Weegee's iconic 1940 image of Coney Island beachgoers jammed together like sardines today hangs in restaurants up and down the boardwalk, a memento of the glory days.

In the ensuing decades, population loss, television, cars and air conditioning undercut Coney Island's appeal. New York's urban planning czar, Robert Moses, hated its tawdry arcades and thrill rides. He transformed the eastern end of the amusement district into a home for the relocated New York Aquarium. The housing projects with which he rebuilt Coney Island became some of the city's most depressed and dangerous.

As the city grew rapidly in the '90s, Mayor Rudolph Giuliani set his sights on Coney Island. Like Moses before him, he bulldozed a roller coaster to build a recreational facility, this time a minor league ballpark for the Brooklyn Cyclones. The Bloomberg administration eyed the island as a potential site for the 2012 Olympics, and in 2003, commissioned the Coney Island Development Corporation (CIDC) to examine the possibility of revising the restrictive C7 zoning that since 1961 had sheltered carnies and coasters (and a few vacant lots, as well) from market forces.

But a Brooklyn developer named Joe Sitt stole the limelight from CIDC, announcing a $2 billion plan in September 2005 that made the Las Vegas Strip look dull. Sitt had shrewdly purchased over a dozen acres of the old amusement park in anticipation of a rezoning gold rush, and hoped to bring in marquee clients like Dave and Buster’s, Ripley’s Believe it or Not, and the Hard Rock Café.

It's fair to say New Yorkers were horrified by Sitt's plan -- he responded by toning it down in later renditions -- but what happened next was worse. Unable to build on his new land, Sitt chose instead to destroy it. Two years after his gaudy dreamchild was plastered on the cover of New York magazine, his development company, Thor Equities, began to evict tenants in what was both a premature move towards development and, many observers reckoned, an attempt to force the city's hand. Coney Island grew barren. "They paved paradise to put up…. what exactly?" asked the Brooklyn Paper.

Old-timers had seen this picture before: In 1965, Fred Trump (father of Donald) bought and bulldozed parts of Steeplechase Park before the Landmarks Commission could intervene, in the hopes of forcing a zoning change. City Planning did not acquiesce, and the Parks Department bought the property four years later.

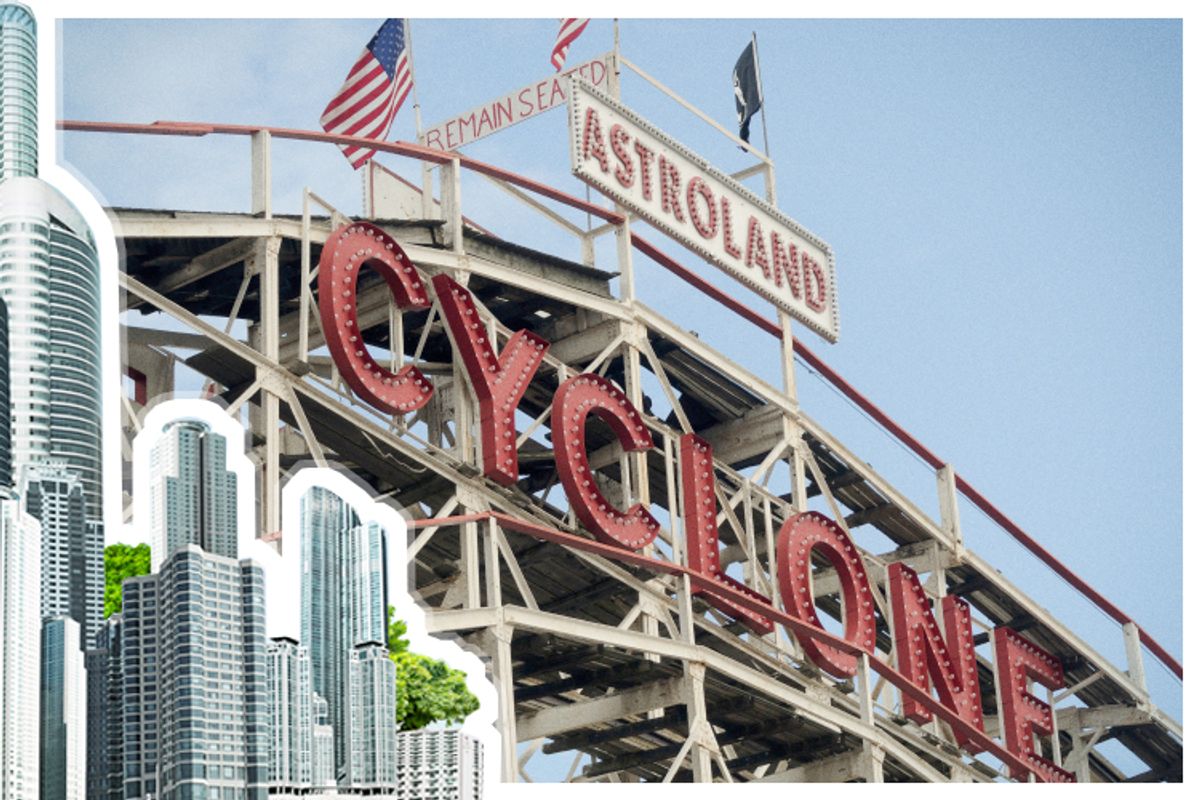

After Sitt was through, the Coney Island Batting Range, Mini Golf, Bumper Boats, and the International Speedway Go-Kart Track had all disappeared. Thor Equities bought Astroland, the amusement complex that had anchored the site since 1962, in 2006. The next year, Thor raised their rent by a factor of 15. Astroland closed too. The eclectic mix of small-time operators and big parks that made Coney Island famous was gone.

It was the low point in Coney Island history. "It was on the verge of collapse," says Dick Zigun, who runs the arts organization Coney Island USA.

That year, Amy Nicholson began filming "Zipper," a documentary that chronicles the evolution of Coney Island through the story of Eddie Miranda, the operator of that legendary carnival ride. Nicholson's film, playing now in New York and Los Angeles, recounts an excellent if weighted (spoiler alert: the Zipper doesn't fare well) history of the machinations that led to the final rezoning in 2009. In spite of protests, the area reserved for outdoor amusements was reduced from over 40 acres to 15, and later, in the proposal that passed the city council, to nine. That November, the city purchased 6.9 acres of land from Sitt at a cost of $95.6 million, or $318 per square foot.

The reason for the final reduction in amusement park territory, as outlined in a 2009 Executive Summary, lay in the city's desire to make Coney Island a year-round destination. More "normal" commercial property development -- as opposed to summer pleasures like roller coasters and bumper cars -- would produce more jobs and more tax revenue. Median income in Coney Island in 2010 was $27,186, half the New York City level.

Domenic M. Recchia Jr., the city councilman who has represented Coney Island since 2002 and shepherded rezoning through the city council, was a key supporter of this concept. "One of my dreams," he says in "Zipper," "is to build an indoor water park hotel." But, he conceded, even a Barnes & Noble would be a great addition to the neighborhood.

Chuck Reichenthal, the manager of Brooklyn Community District 13, which includes Coney Island, stressed the importance of year-round jobs. He was no fan of Sitt's proposal, but, he said, the rezoning was one of the best things to happen there. "There's no reason why we can't figure out things to do during the whole year," he said. With indoor restaurants finally permitted inside the former C7 zoning, he imagines a future of year-round tourism, bolstered by the Abe Stark Ice Rink and hopefully, one day, the rehabilitation of the grand Shore Theater, which closed in 1973.

He touted the number of year-round jobs already created at places like Grimaldi’s Pizza, the Brooklyn stalwart that opened another branch on Surf Avenue. Tom's Restaurant, an offshoot of the famous Prospect Heights Diner, opened last summer on the boardwalk and has plans to stay open all winter. Whether the relaxed zoning can in fact bolster Coney Island’s year-round appeal, once the thrill rides have closed and the beach is cased in snow, remains to be seen.

Zigun, who mentioned that Coney Island USA has received support from the Bloomberg administration, offered a more tempered assessment. "Though we're a different amusement park than we were 10 years ago, we're still viable," he said. He had been an outspoken advocate for preserving amusements, and resigned in protest from the Coney Island Development Corporation in 2008. But his opinion of the rezoning softened as Coney Island was reborn. “What’s happened in the past four years is a reaction to what you see in the movie,” he said, meaning "The Zipper." “It’s not so bad.”

The amusements are back in force. After buying Sitt's land, the Bloomberg administration moved rapidly to fix the damage inflicted during the rezoning speculation. In February of 2010, the mayor announced an agreement with Central Amusement International, a New Jersey subsidiary of the Italian amusement giant Zamperla Group. For a token concession payment of $100,000 a year, CAI has transformed the six-acre, $95 million parcel into a thriving theme park. The name, Luna Park, is a tribute to the Coney Island of yore.

To stand on West 12th Street, with the glimmering new coasters of Luna Park on one side and the Ghost Hole at Deno's across the street, with its charming hand-painted ghouls, is to see the difference between the old Coney Island and the new. Since the rezoning talk began a decade ago, more than 40 local businesses have been forced out, from carnival games to roller coasters to bars.

Under Central Amusement's watch, the boardwalk has turned over as well. Two summers ago, CAI evicted all but two establishments, Nathan’s Famous and the clothing boutique Lola Star, from the famous stretch. (Two old-timers, Paul's Daughter (1962) and Ruby's Grill (1934) later came to an agreement and have renewed their leases.) These days, the annual rent paid to CAI for a boardwalk storefront, though technically subject to city approval, can run higher than what CAI pays the Parks Department for the entire six-acre plot.

What's in store for the amusement area? "We will never make Disney here," CAI president Valero Ferrari told the New York Times, "but it will be something more… refined, cleaner, a little more year-round, if that's possible, with sit-down restaurants and sports bars."

The company hired Miami Beach restaurateur Michele Merlo to re-envision the boardwalk, with plans that call for, among other things, a food court with international cuisine. "Maybe one day," he said in an interview with New York 1, “you can come and read your book outside on this nice boardwalk, sit in nice comfortable chairs and have a nice cappuccino or ice coffee."

Just down the walk from one of Merlo’s imports, Coney Cones, there’s a sign for Deno’s Wonder Wheel that reads, “They Don’t Build Them Like This Anymore!” It seems like a strange way to advertise a theme park ride, but it’s a fitting epitaph for the weird and wonderful hodgepodge that was Coney Island.

Shares