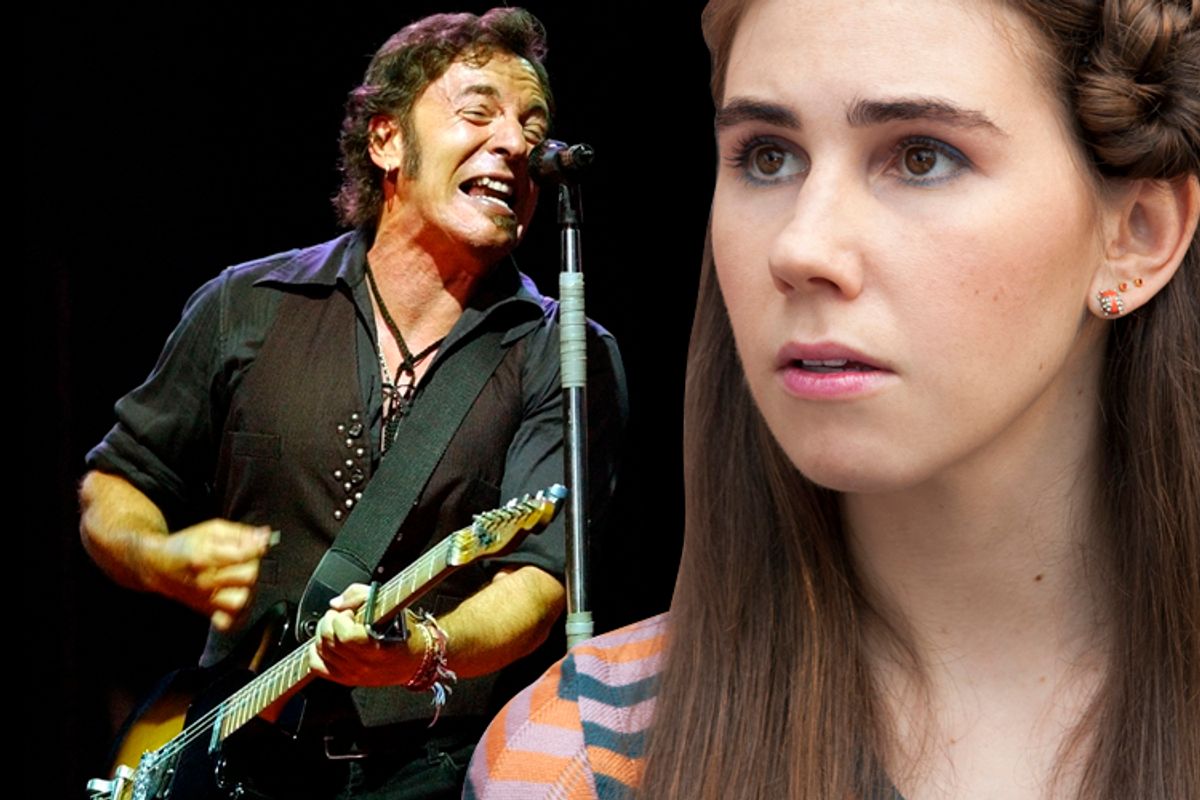

Every few weeks or so, I’ll be talking to someone at a bar or club or house party, and the conversation will inevitably turn toward Bruce Springsteen. The exchange is usually as follows:

BAR PATRON/PARTY GUEST: So, what kind of music do you listen to?

ME: Oh, a little bit of everything … blues, jazz, funk, Bruce Springsteen (brief pause) … you know, my tastes are super eclectic.

BAR PATRON/PARTY GUEST: Um, why do you like Springsteen?

ME: So, you don’t like Bruce Springsteen?

BAR PATRON/PARTY GUEST: Ugh. No.

(Long pause)

ME: (Shuffling away while muttering angrily, like an elderly woman being chastised for feeding pigeons) Well, you should.

This person will then enumerate the list of reasons why he dislikes Bruce Springsteen, usually employing four out of six of the following arguments:

- He’s old.

- He sucks.

- He sucks because he’s old.

- He’s old because he sucks.

- He sings about being a member of the working class even though he’s made millions and millions of dollars over the past 30 years

- “Born in the USA” sucks.

In my 24 years as a die-hard Bruce fan, I have had this conversation approximately eight or nine hundred thousand times. While the people on the other end tend to skew toward a specific demographic — white, male, in a creative profession, dating someone with bangs and an Egon Schiele tattoo — they come from a wide range of socioeconomic and cultural backgrounds, from Bushwick installation artists to a bouncer I met in Ireland, who used his loathing for "Born in the USA" as a launchpad for a diatribe against Michelle Obama and the Gregorian calendar. Yet despite their many differences, these people have two things in common: They’re all around my age (i.e., in their early to mid-20s), and they all loathe Bruce Springsteen. The iron fist of Bruce hatred has come down on millennials, and it has struck even the best and brightest of us.

To those not firmly ensconced in Boss fan culture, Springsteen’s unpopularity among hipsters and drunken racists might not seem like much cause for concern. Without a doubt, Bruce Springsteen is one of the most beloved American rock musicians of all time: He’s won 20 Grammys, has been inducted into the Hall of Fame, and has appeared on the cover of Rolling Stone enough that he’s probably single-handedly responsible for keeping it in circulation. He routinely sells out his world tours (his latest, for 2012’s "Wrecking Ball," was just extended till February), and his following, as seen in the July 2013 documentary "Springsteen and I," is so rabidly devoted to him that if Bruce wanted to record an album of Wesley Willis covers, there’d be thousands of bootleg YouTube videos of him singing “Suck a Cheetah’s Dick” at his Saskatchewan show.

But here’s the thing about Bruce’s fan base: It may be huge, and it may be rabidly loyal, but it is old. Like, Peter, Paul and Mary fan old, to the point where David Brooks, in a recent New York Times editorial, referred to American Springsteen fans as “hitting their AARP years, or deep into them” (in Europe, where Springsteen’s fans are arguably even more fervent than their U.S. counterparts, the crowds tend to skew much younger). If you survey the audience at a Springsteen concert, you’ll see soccer moms and paunchy cops and ex-high school quarterbacks who are now working at insurance companies; there will be a smattering of frat boys and maybe the odd hipster in a battered "Asbury Park" tee, but on the whole millennials are vastly underrepresented. Put simply: If you gathered 50,000 Meadowlands ticketholders, maybe 15 of them could correctly identify Skrillex in a lineup.

To a certain degree, this makes sense: Because Springsteen’s debut album, "Greetings From Asbury Park," was released four decades ago, it’s reasonable to assume that those born between 1985 and 1995 (the “Tunnel of Love/Ghost of Tom Joad” demographic) would have less of an interest in him. “The idea of, when I was 18, liking a musician whose first album came out 40 years earlier — for me, that'd be like being really into Glenn Miller or something,” Peter Ames Carlin, the author of the 2012 Springsteen biography "Bruce," says. Yet even for those of my generation who have a strong interest in older music, Springsteen is often associated with what fellow Springsteen-ographer Marc Dolan refers to as “dad rock.”

“There are a great many [Springsteen fans] who embrace the length and breadth of Springsteen’s work, but the worst members of U.S. audiences at his concerts often want no more than a nostalgia fest,” says Dolan, the author of "Bruce Springsteen and the Promise of Rock and Roll." “And if the crowd is most engaged when your parents are pumping their fists to 'Out in the Street,' remembering the good times before you were born ... well, yeah, maybe I wouldn't embrace that music if I was 20-something either.”

In my experience, people my age who have even a passing interest in music and rock history consider Bruce a mawkish rock dinosaur, or what my friend Doug, a musician, refers to as “a physically fit, raspy-voiced oldie with veins popping out of his neck.” This probably stems at least in part from the fact that Bruce does not quite adhere to the hipster conception of an American rock hero: his sweat-drenched brand of earnest populism is at odds with Lou Reed’s chain-smoking nihilism, or Jagger’s strutting, high-cheekboned gender-fuckery. These dudes bear few, if any, artistic similarities to Springsteen, yet they all enjoy a certain type of indie cred that Bruce does not, in part because today, they don’t look like they’re working too hard (or at all, really). Working hard — to entertain and enlighten, to reach new fans and continue to rouse the passions of old ones — is what Bruce does best. It’s why his fans love him, but in this irony-drenched age of insta-stardom, hard work counts far less than it used to.

Even in the classic rock canon at large, Springsteen is something of an idiosyncracy: He’s not as grizzled as Dylan or as jaded as Neil Young (although he is at least recently more prolific — and arguably consistently better — than both), nor does he have the swagger of a Robert Plant, or the dead sexiness (or sexy deadness) of a Kurt Cobain. My friend Ezra, a longtime Bruce hater, sums Bruce’s role in the rock god pantheon thusly: “MJ makes you want to dance, Dylan makes you want to smoke, Zeppelin makes you want to be an excitable teenager. I don’t know where Bruce would fit in my life, besides not liking his music.”

Now, I am not going to deconstruct the above anti-Bruce arguments, because people are entitled to their opinions (even when they are, in this case, egregiously, desperately wrong). I’m not going to proffer an in-depth sociological explanation for this sweeping wave of Bruce hatred, because I think “a widespread generational embrace of postmodern irony accompanied by a universal rejection of all that is honest and genuine and joyous and sincere” pretty much says it all. And I’m not going to say that having to defend my favorite musician, over and over and over again, with people who know Bruce only as that guy who wrote a pro-Reagan song in the '80s and once smushed his testicles into a cameraman during the Super Bowl halftime show, makes me angry, because it doesn’t.

It just makes me sad. Profoundly, unspeakably sad.

It makes me sad that these people will never listen to the opening chords of “Jungleland,” that they’ll never feel their hearts rise in their throats and their guts twist during Clarence Clemons’ sax solo. It makes me sad that they’ll never pump their fists to the triumphant, one-two-three gut punch opening bars of “Rosalita,” or roll their car windows down while waving their hands with the little pretties in “Tenth Avenue Freeze-Out,” or get ready to go out on a Friday while listening to Bruce espouse the endless possibilities of the “Night.”

It makes me sad that future generations of restless suburban kids who want more out of life than day trips to the city on the LIRR won’t listen to “Badlands” or “Thunder Road” or “I’m on Fire” and be able to put a name to the desire for speed, for movement, the itch in their joints and the hum in the engines of their cars that’s begging them to run or drive or fly as fast as they can to anyplace that’s bigger than them, anyplace that has enough room to spare for all their wanting.

That feeling of restlessness and exhilaration that Bruce speaks to in his songs will be around forever. But Bruce won’t be. Dude is pushing 65. He can’t go smashing his balls into cameramen forever. And if this trend continues – if his music is listened to by progressively fewer and fewer members of younger generations – his fans won’t be around for much longer, either. He won’t reach the level of Zeppelin or Dylan or Kurt Cobain or Neil Young, artists who are still popular among those born decades after the pinnacle of their popularity. In 20 years, he will be a dinosaur, a Glenn Miller, duly respected in record books and Rolling Stone but virtually ignored by people born from 1995 onward. He will be known as the guy who sucked because he was old, or the guy who was old because he sucked.

There is a small glimmer of hope for the continuation of the Boss’s legacy, however, which comes in the form of the next generation. I have met one of their number. She was 10 years old, and her name was Amanda. She was one of my campers when I worked as a bus counselor a few years ago, and when I wasn’t cleaning up puke or yelling at kids to buckle their seatbelts, I would sit with her and we would listen to "Magic" on her iPod while we talked about Bruce.

She told me that she had already been to two concerts, and that her parents played Bruce around the house all the time. She told me that she liked to watch the 2000 DVD of his show from Madison Square Garden, and that she loved to dance with her dad when Bruce kicked off his set with “Prove It All Night.” I told her I used to do the same thing with my dad, who also introduced me to Bruce: I wasn’t particularly cool in high school, so I spent countless Saturday nights watching the MSG show with my dad while we got drunk and danced to “My Love Will Not Let You Down.”

“Is there anybody alive out there?!?!?!?!” Bruce would scream on the TV, and we’d imitate the crowd roaring back. Then my mother would yell at us to turn it down, and my father would begrudgingly comply, only to turn the volume up on Nils Lofgren’s solo in “Youngstown.” It is, far and away, my favorite memory from high school.

I told Amanda that my dad was also the reason why I loved Springsteen in the first place, and why I continued to hold strong to that love long after I actually started going out on Saturday nights and quibbling over Bruce with racists at bars. And it occurred to me that when Amanda got older, that bond would keep her relationship with Bruce strong as well, against the protestations of her anti-Bruce peers. I had faith that her fandom would stay strong in a Bruce-loathing world that was hostile to sincerity and rewarding of artifice, and I still hold out a tiny bit of hope that eventually, my compatriots will see the error of their ways and follow suit.

So to those born between the releases of "Tunnel of Love" and "Tom Joad": please Spotify "The Wild, the Innocent, and the E Street Shuffle." Get “Darkness on the Edge of Town” while you’re at it (though you can skip “Candy’s Room”), and “Born to Run,” and “Nebraska,” and “The Rising.” Watch a few of his shows on YouTube, then look me in the eye and tell me he doesn’t fit into your life, somehow; that he doesn’t make you feel exhilarated and overwhelmed and joyful and heartbroken and hot-blooded and alive. Because the next time Bruce asks me, “Is there anybody alive out there?” I don’t want to be lying on behalf of my generation when I shout back, “Yes.”

This piece is a revised and expanded version of a blog post the author wrote in 2010.

Shares