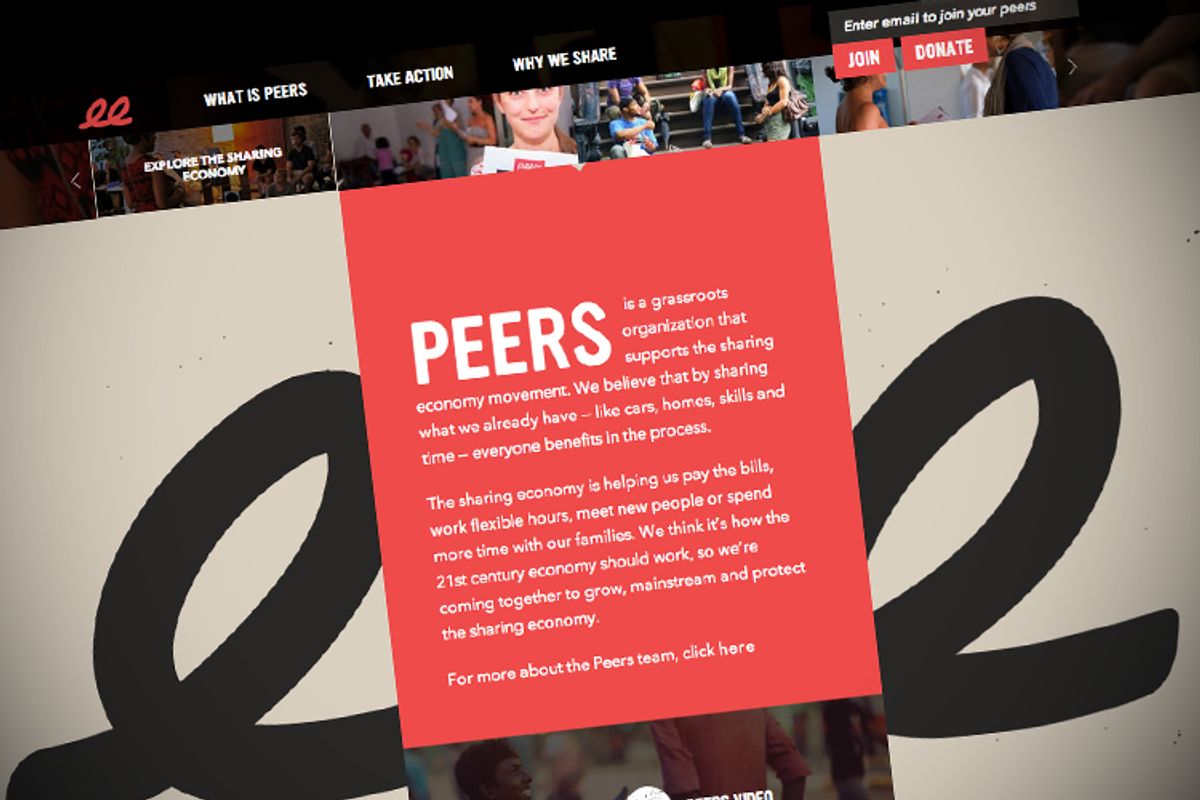

The last sentence of my August post about Peers, the newly formed advocacy group pushing for the growth of the "sharing economy," was "If Peers is where the grass roots intersects with state-of-the-art Silicon Valley capitalism, it’s going to be an organization to watch."

Now we have a test.

Early this month, Peers rallied its members against a proposal to ban the room-sharing start-up Airbnb in the Silver Lake neighborhood of Los Angeles.

[embedtweet id="376764636890419200"]

The contours of the debate in Silver Lake are similar to those playing out across the country. Some residents objected to their neighbors turning their homes into temporary hotels. Laws on the books designed to protect the hotel industry technically make renting out your home for less than 30 days illegal. At the same time, other residents were eager to make extra cash in a tight economy.

But let's put aside the relative pros and cons of that debate for now. The most interesting thing about Peers' action alert -- the first such move since the organization was founded -- is how well it worked. An on-the-scene report from Fast Company's Zak Stone reports that a Neighborhood Council meeting held Monday Sept. 9 to consider the proposed ban was overwhelmingly packed by Airbnb supporters.

Airbnb supporters far outnumbered opponents and audibly booed ban-supporters like Scott. (A volunteer at the church where the meeting was held counted “a dozen people crying” on their way out.) But more than just demonstrate their passion for the service, they gave a taste of the future of the sharing economy as it becomes an organized political force--albeit on a small-scale--thanks in part to a new, international activist group called Peers, whose mission is “to grow the sharing economy, to mainstream it, to tell its story, and to protect it,” in the words of founder Natalie Foster.

When Peers got wind from Sliver Lake Airbnb host Matthew Desario about the ban proposal, they helped Desario post and distribute an online petition in support of Airbnb--which has since been signed 5,000 times--and get the word out about the September 9 meeting, resulting in high attendance from Airbnb backers. It was the first local action for the young, Bay Area-based organization, but a taste of what may become common as more and more cities respond to the growth of the sharing economy with bans and fines.

When you stop to think about it, the potency of Peers' activism makes sense. Online organizing and the sharing economy make for a natural fit. The mobile first generation wants their sharing apps, and seems ready to stand up and be counted for them. Politicians entrusted with the job regulating these new "collaborative consumption" services will surely take notice.

Foster told me in August that the genesis of Peers traces back to a "seed" conversation among stakeholders funded by Airbnb at Purpose.com. That money looks well-spent. Foster also told me that Airbnb is not a "lobbying" organization. That may be technically true insofar as the legal definition is concerned. But in terms of the practice of pure politics, Peers is clearly a player.

Shares