After a summer of breezy beach reads, book publishers have gotten down to the weightier business of big – in some cases gargantuan – fall biographies.

This season’s buzziest bio is Mark Lewisohn’s exhaustively researched, long-awaited, super-sized, definitive biography of The Beatles that is so big it has three names – “Tune In: The Beatles: All These Years” – and will be parceled out in three volumes.

“Tune In” covers The Beatles only through the end of 1962 – before the first album, the hippie haircuts or Yoko Ono – but is a surprisingly lean read for 944 pages. The book is out this week, and Lewisohn is already at work on the second volume.

“The whole essence of this is to not cut any corners, to do this as well as possible, to leave no stone unturned, because it will never be done so thoroughly again,” Lewisohn said. “It can’t be done so thoroughly again because the participants won’t be around anymore and, to be honest, no one has had the kind of archive access I have had.”

Lewisohn spent a decade researching and writing “Tune In.” The publishers were expecting 250,000 words [about 1,000 pages], and Lewisohn said he was nervous when he turned a manuscript of 780,000 words. That wasn’t the entire series; it was just the first book.

“My greatest fear at that point was that the publishers would insist that I deliver only 250,000 and that I would have to cut two-thirds of the book out,” Lewisohn said. “Well, that didn’t happen. When the British publishing company [Little, Brown Publishing Group] read the whole thing, they said, ‘This is fantastic. We’d love to publish this, but we do still want the 250,000-word book.’ And so did the American publisher, Crown Archetype [an imprint of Random House].”

The result was two versions of the Beatles book – the 944-page standard edition and a 1,728-page, two-book special edition that, as the book’s U.K. web site notes, “will sit within a specially designed box and lid featuring soft touch and varnish finishes.” (Crown Archetype has not announced plans yet for a U.S. printing of the special edition.)

Rather than turn the longer version over to editors to pare down, Lewisohn did the painstaking abridgement himself – focusing on the Fab Four and editing, editing, editing to bring out the definitive story.

“You have to know as a writer what is interesting and what isn’t,” he said. “I only write what I feel helps the reader to understand the people and the moment and the situation. Anything above that is too much.”

In a fragmented, niche-marketed industry where a hit book can mean selling 50,000 copies, several big bios have been breakout hits in recent years. The biggest hits – no surprise here – are the ones with fascinating, world-changing stories to tell.

Steve Jobs didn’t spend his life punching a clock; he was the creative force behind Pixar Animation, the Macintosh computer and the iPhone. His story and Walter Isaacson’s deft retelling of it were the reasons his “Steve Jobs,” published in 2011, has been a monster hit – selling more than 1.7 million copies in hardcover and paperback, according to data collected by Nielsen Bookscan and provided to Salon.com. Nielsen Bookscan tracks sales at 85 percent of retailers and does not include e-book sales, which are often more than double the number of print sales.

“People crave insights into a brilliant person’s mind. What makes them tick?” said Jennifer Tung, editorial director for nonfiction at Ballantine Bantam Dell, an imprint of Random House. “It’s kind of a hybrid of voyeurism and self-help.”

Doris Kearns Goodwin’s “Team of Rivals,” published in 2005 and one of the source books for Steven Spielberg’s “Lincoln,” has sold more than 1.5 million print copies. Jon Meacham’s “American Lion: Andrew Jackson in the White House," published in 2008, has sold more than 580,000 print copies.

“Biography interest correlates to whether readers think their lives are within their control,” said Scott Moyers, publisher of Penguin Press, an imprint of Penguin Group. “[It] has to do with the power of exemplary human stories to inspire us — the promise is that there’s something about genius, about the proximity to it, that can rub off.”

Moyers said the aspirational appeal of biography dates as far back as Parson Weems’s popular 1800 biography, “The Life of Washington,” which included the almost certainly untrue story about George Washington chopping down the cherry tree and depicted the first president as a product of his high moral character. Horatio Alger’s rags-to-riches tales, where ingenuity and hard work were the keys to success, were popular from the 1860s to the turn of the century.

So, are the 800-page gorillas of the biography genre popular because they’re such big books, or is the length more a necessity of telling a big, multifaceted story?

“I think it’s a little of both,” Moyers said. Not every life merits an 800-word book, but big books succeed when they get at the truth of big lives. “It’s also true that most people can feel they’ve gotten their money’s worth from a fat biography without having read every last word — which is a good thing, because it’s safe to say that most people don’t.”

This fall season, the big word in big biographies is “definitive.”

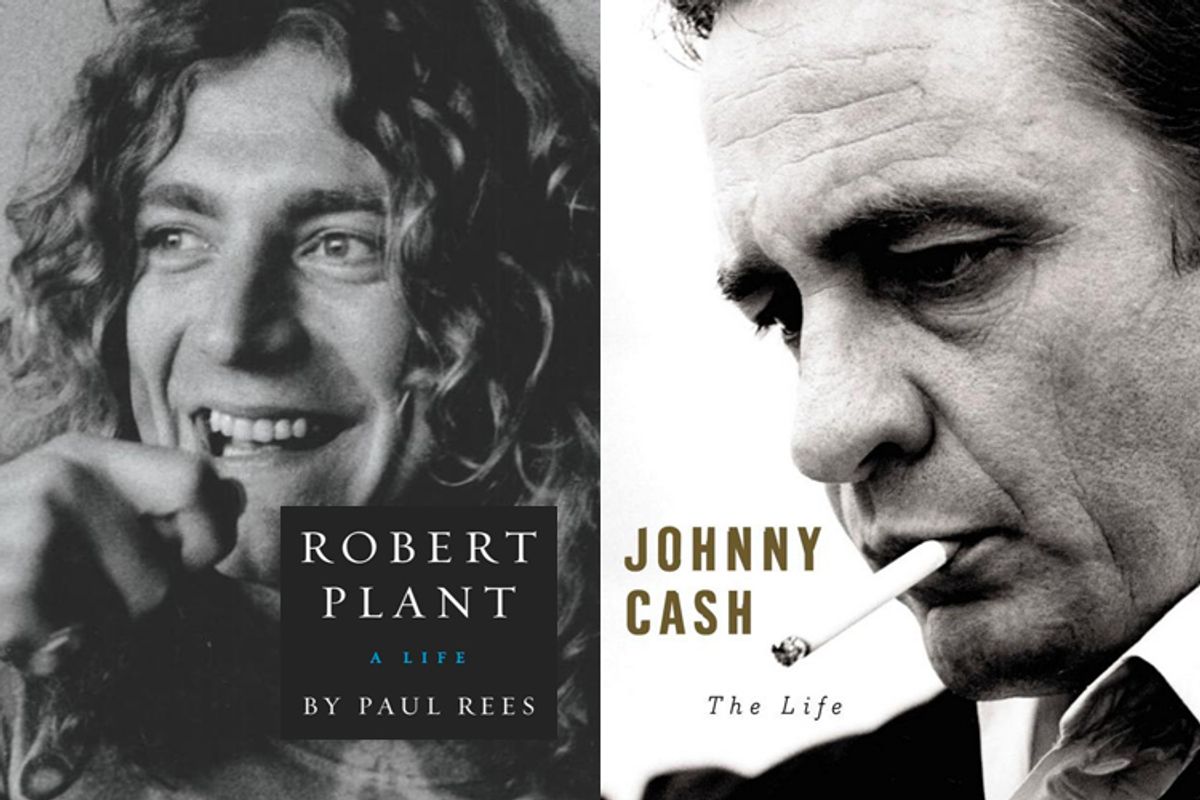

A. Scott Berg’s publisher says “Wilson,” a biography of Woodrow Wilson, is “the definitive and revelatory biography of one of the great American figures of modern times.” Paul Rees’s “Robert Plant: A Life” is “the definitive biography of Led Zeppelin’s legendary frontman.” Dick Lehr and Gerard O’Neill’s “Whitey: The Life of America’s Most Notorious Mob Boss” is “the definitive biography of Whitey Bulger, the most brutal and sadistic crime boss since Al Capone.” Robert Hilburn’s “Johnny Cash: The Life” is “the definitive, intimate, no-holds-barred biography of Johnny Cash.”

That’s not a definitive list, but you get the idea.

“I do see the word frequently,” said John Parsley, an executive editor at Little, Brown & Co. “And I’m careful not to use it unless I mean it.”

With Robert Hilburn’s “Johnny Cash” biography, which Parsley edited, he means it. In January 1968, Hilburn covered Cash’s storied concert at Folsom State Prison just outside of Sacramento, Calif., as a young freelance writer for the Los Angeles Times. Hilburn would soon begin a 35-year run as music critic for the Los Angeles Times, and he interviewed Cash, who died in 2003, many times.

“It’s unusual to find an author who knows the subject well and knows the people within his circle,” Parsley said. “Robert Hilburn had that kind of access.”

David J. Garrow, who won a Pulitzer Prize for “Bearing the Cross,” a biography of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and is writing a book about President Obama, said there will be a place for new biographies of familiar figures as long as there are significant new facts to reveal.

“At some point in time we’ll get Lincoln and Jefferson biographies that could be definitive into infinity,” Garrow said. “For George Bush or Barack Obama or Martin Luther King, we’re still going to learn new things 20 years from now.”

Eamon Dolan, who edits his own imprint at Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, said he sees biographies as either “micro” or “macro,” and he has one of each out this fall. The “micro” book is “Johnny Carson” by Henry Bushkin, which focuses on Carson during the years that Bushkin was his personal attorney and an executive at Carson Productions.

“It’s about the 18 most interesting years in Carson’s life,” Dolan said, “It felt as I was reading that I was seeing essential truths about Carson that I had not seen anywhere else. That is a certain kind of definitiveness.”

The book is more a memoir of Bushkin’s years with Johnny Carson than a biography, but it is a revealing portrait of a different Carson than the one who wisecracked with celebrities on “The Tonight Show.” Bushkin reveals an imperious, withdrawn and often cold Carson who ended a nearly two-decade relationship with Bushkin over a business dispute – and then sued Bushkin.

The “macro” book is “Fosse” by Sam Wasson, a biography of choreographer Bob Fosse.

“This is the opposite – could not be more macro,” Dolan said. “It starts in his childhood at his first dance lesson and stops 60 years later when he dies. There will not be a more revelatory book about Fosse, which is a different kind of definitiveness.”

Brian Jay Jones, author of "Jim Henson: The Biography," mined all media for his biography of the enigmatic Muppets creator who died in 1990. Jones interviewed dozens of people, watched hours of "Sesame Street," "The Muppet Show," and scads of clips and interviews, and spent weeks poring over everything from scripts to plans for unfinished projects at the Jim Henson Co. archive.

"You immerse yourself in someone's life for the entire time you're doing it," Jones said. "I wanted to get [Henson] to stand in the spotlight, which he never really liked to do. He always said he was much more comfortable letting Kermit do the talking for him."

So what does definitive mean to a biographer who spent 13 years researching and writing “Wilson,” his cradle-to-grave biography of the Progressive Era president?

“Here’s what I think it means,” A. Scott Berg said. “If you walk into a bookstore and you want to read a book about Woodrow Wilson, I like to think my book is the definitive one, which is the most telling book about the subject. I like to think mine is the most historically accurate and the most incisive and insightful about the character that I’m writing about.”

Shares