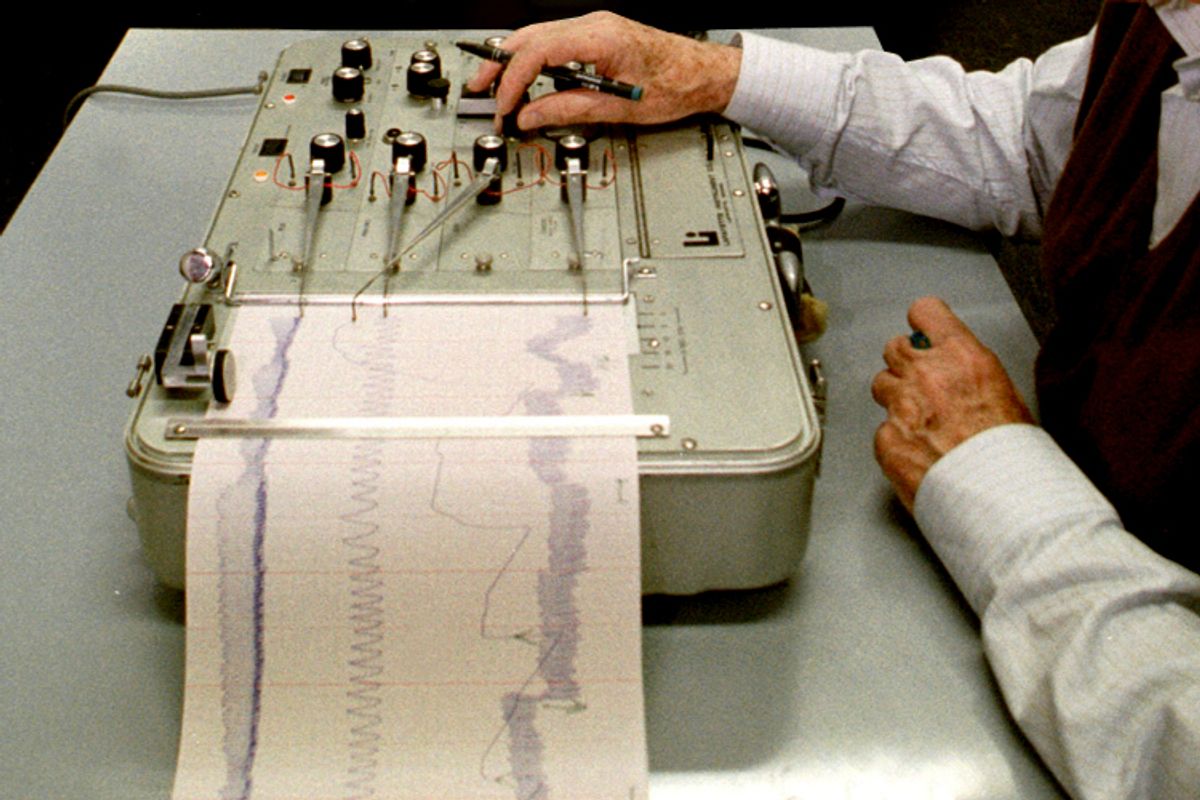

Strapped to a straight-backed metal chair, I plant my feet firmly on the ground and try not to think about the electrodes and sweat monitors attached to my hands and chest. The room is silent – no air-conditioning hum, no buzz from the blue fluorescent lights.

Angela, the CIA polygraph technician, sits in a chair facing me and begins.

“Have you disclosed all of your illegal drug use to the Agency?”

I say yes. I had told them about trying marijuana, so I’m covered. Angela smiles. She continues with the next two questions, which I answer easily. Then the final one:

“Are you hiding any contacts with foreign government officials?”

My stomach lurches at the word “hiding,” but the answer is obvious: no. I say I don’t have any contacts with foreign government officials.

The polygraph screen goes wild. I inhale sharply, my heart pounding.

“Let’s try that again,” Angela says, and repeats the question. My hands shake as I remind myself I have nothing to hide – nothing big anyway. But I fail again. My body is betraying me.

Angela tells me to breathe deeply and relax. I fidget in the metal chair. Closing my eyes, I picture the ocean. And then I panic.

“What if I had contact with a foreign government official, and I don’t remember?” I ask.

Angela turns stern and cold. “You didn’t forget. You know who you know. Tell me who it is.”

I have no names to give her.

She softens, and suggests that perhaps I’m just nervous. “There’s something tripping you up,” she says gently, almost hypnotically. “You’re hiding something. What are you hiding?”

Truthfully, I feel like I’ve been hiding a lot. I start rattling off my secrets: “I’m not really in love with my boyfriend. I sometimes call in sick to work and go visit the pandas at the zoo. I tell people I loved my dog at first sight, but I hated him when he was a puppy. I faked my way through ‘Great Expectations’ in high school. Do you want me to keep going?”

She doesn’t. So I don’t mention the one obvious secret I’ve been hiding from everyone I love: I’m being recruited for the CIA’s clandestine service. That’s why I’m taking the polygraph.

Two years earlier, as a J.D./Ph.D. student fluent in Turkish, I believed I would make an ideal spy. I was also floundering. I didn’t want to be a lawyer or a professor, but my post-college dream job as a family planning and HIV test counselor had burned me out faster than I’d expected. Promising constant change, the Agency beckoned.

After watching a video starring Jennifer Garner on the CIA website, I submitted my online application, and soon heard back from a recruiter named Fay. Fay assigned me a reading list of CIA memoirs, and promised to be in touch. She then called me every few weeks from an unidentified number, asking about the memoirs and assessing my enthusiasm and commitment to the job. Fay never revealed her last name. Between our conversations, I imagined destroying terrorist cells and exposing coups d’état.

I passed history, geography and foreign language exams. For each new phase of recruitment, I was assigned a new first-name-only recruiter. They would regularly call with instructions: meet at an unmarked office building in Virginia; write us an essay on your ideas about service and sacrifice. I was given personality tests, evaluated by a psychiatrist, and put through grueling role-plays. Once I was given the following scenario:

You’re meeting with an Emirati government official in a hotel room in Dubai. He’s a member of the royal family and an informant for the U.S. The police knock on the door. If you’re found with this man, you will be imprisoned, and his life will be in danger. What do you do?

I said I’d climb out the window.

“They have the hotel surrounded,” my recruiter, Barbara, said.

“Then I’d pretend we were on a date,” I suggested. “It might be embarrassing, but it wouldn’t be illegal.”

Barbara said my solution wasn’t credible. Instead, the informant and I should both get naked and “into position.” A date was too transparent; sex was convincing. I felt bad that I hadn’t figured this out on my own. Barbara told me that Valerie Plame hadn’t aced that role-play either.

I had to disclose my medical, financial and travel records; the names of essentially everyone who had ever known me; my own closet skeletons, and those of my loved ones. My recruiters learned about family members with addiction, mental illness and felony convictions. They saw my crippling debt. They spoke with my former landlords and heard that I paid rent on time but had a neurotic dog. I felt exposed, but exhilarated. When I told a recruiter I had tried marijuana, he smiled, shrugged and said, “I know.” Did he know I had tried marijuana, I wondered, or did he know that I had smoked it in a dorm room in Krakow in 1995 with my older boyfriend and some Polish theology students?

I was allowed to tell anyone I trusted about my application process, but I was warned that I might compromise their safety. I never told my parents or my best friend. I told the guy I was dating when I first applied, and the guy I lived with during the second year of my recruitment. They both found my clandestine prospects alluring. Per Agency guidelines, I should have asked the hard questions: Could you be married to a spy? Would you be willing to relocate every few years? What if I served in a dangerous region and you couldn’t accompany me? But I didn’t ask; I wanted to be sexy, not high maintenance.

When the FBI asked my father to verify my childhood address, I told him I was applying to the State Department. I was visiting my aunt when my phone rang in the middle of the night to schedule my next interview. I told her my friend was having a pregnancy crisis. When I graduated from law school and joined a corporate firm, my friends raised their eyebrows. I had always insisted I’d never practice law; suddenly I acted excited about securities litigation. Secretly, I knew I’d soon leave this miserable job to go undercover in Syria or Uzbekistan. With an exit strategy, I could fake anything.

After the two-year recruitment process, the CIA offered me a job. And then, after celebrating with a bottle of wine and asking my boyfriend if he’d take care of my dog while I learned how to fire weapons in the Shenandoah wilderness, I received the last phone call I’d ever get from the Agency. I was asked to take the polygraph.

Three days after failing the exam, the letter arrived in a thin, unmarked envelope from Yoder & Young Associates, a fake recruitment firm. I knew what it said, but I still had to sit down to read it. Curled into a corner of my couch, I pulled my aunt’s knitted afghan around me and read:

Dear Ms. Green:

Unfortunately, we have determined that you are unsuitable for employment with our organization at this time. There is no appeal of this decision.

Like all correspondence from Yoder & Young, the letter was vague and generic, with no return address. I could throw it into the trash, anyone could find it, and nobody would know what the letter really said: I would never be a spy.

I thought about all the lies I’d been forced to tell over the past two years – lies to explain why I got phone calls at 3 a.m. or had to fly to Virginia for last-minute business trips. Tears ran down my face with uncharacteristic abandon as I wondered what lies I’d tell next to explain my inevitable despondency.

I had to figure out what I wanted to do, how I’d leave my job and pursue a different dream, how I’d find adventure and mystique without espionage. More difficult was figuring out how to live honestly. How to say, “I hate my job, but I don’t have an exit plan.”

Six years after my rejection, I’m enjoying the company of my dog, turning off my cellphone when I sleep, and traveling a lot with my own passport. Sometimes I watch “Homeland” and cry – not for the obvious reasons, but because I see a world I so desperately wanted to enter. Yet while I’ll (probably) never be naked with a sheik or emir, I’ll get naked with a man I love, and he’ll never have to weigh the sexiness of a spy against the challenges of a clandestine life.

The CIA offered me an escape valve into a world of untrue stories I kept spinning and spinning until the moment came when I could become someone else. But lying to myself was the biggest betrayal of all. I make real-life plans now, analyze career choices, and live with ordinary secrets. I have no glamorous cover. I would probably pass the polygraph test if I took it today.

Shares