Caught like a kid with her hand in the cookie jar, Carol tried to keep her kiddie self-defense class a secret for the first two episodes of "The Walking Dead." Casting herself as some sort of post-apocalyptic Mother Goose, her daily version of storytime ended with a lesson in knifecraft. Once found out, she pleads with Carl like a kid who has gotten a bad report card: Whatever you do—don’t tell Dad! Why, many viewers and critics have wondered, would anyone object to teaching children to defend themselves when walkers are always at the door? Simple. Carol fears that Rick, like his misguided late wife Lori, and like the American viewers who tune in faithfully each week, need children to remain innocent, no matter what the cost. A quick glance at the stories we’ve told ourselves for centuries reveals a persistent tendency to categorize children as one of two things: innocent victims or bad seeds. Carol’s impromptu self-defense classes blurred that line in ways that she feared would scare Rick, as it certainly scares most Americans.

Puritan settlers came to North America quite sure that all children were born evil. John Robinson, a friend of William Bradford and a 17th-century combination of the Marquis de Sade and Benjamin Spock, warned parents that nothing short of repeated, harsh discipline would get the devil out of their little Johns and Abigails. “There is in all children," he warned, "a stubbornness, and stoutness of mind arising from natural pride, that must in the first place, be broken and beaten down."(Feel free to have that piece of pilgrim advice embroidered on napkins for your Thanksgiving festivities this year.)

The age of the helicopter parent we now inhabit would make much more sense to nineteenth-century folks. Enraptured by innocent waifs like Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Little Eva, Charles Dickens’s Little Nell, and countless others, Victorians replaced the Puritan idea of the naturally bad child with its polar opposite—the child simply too good to live. "Uncle Tom’s Cabin’s" Little Eva, a child so angelic that her feet barely seemed to touch the ground, was far too pure a soul to confront the horrors of slavery that surrounded her. When Eva simply hears the story of an abused slave, she transforms from beautiful child to a horror movie spectre, as her “large, mystic eyes dilated with horror, and every drop of blood [was] driven from her lips and cheeks.” Her caretakers accurately diagnose the problem. A story like Prue's “isn't for sweet, delicate young ladies, like you,” declares one of the house slaves. “These yer stories isn't; it's enough to kill 'em!" And indeed they do. Like the child of hipster foodies who stumbles unprotected into the pop-tart aisle, Eva’s access to just one bite of the fruit of knowledge does irreversible damage. She dies within a few chapters, sparking readerly mourning that helped to fuel unprecedented antislavery furor.

So Barack Obama was building on a tradition that went back at least as far as Little Eva when he asked the nation to witness the suffering children being gassed to death in Syria to prepare ourselves for possible war. The victimized child has long functioned as the litmus test for American virtue. We just know we’re on the right side of battle of good and evil when we are avenging lost little angels. The child-victim provides a moral get-out of jail free card. Carol’s worry earlier this season about the reaction to her kiddie knife lessons reflects her knowledge that American adults--even post-apocalypse--are desperately worried about losing the innocent child we rely on to confirm our roles as protectors and heroes. Her own morally suspect actions in "Isolation" prove that she herself is not immune from the need to see herself as a child savior, even at the expense of other innocents. As the virus moves through the prison regardless of Carol's violent attempts to stop it, the desire to isolate the already-exposed children from danger seems to be yet another misguided fantasy.

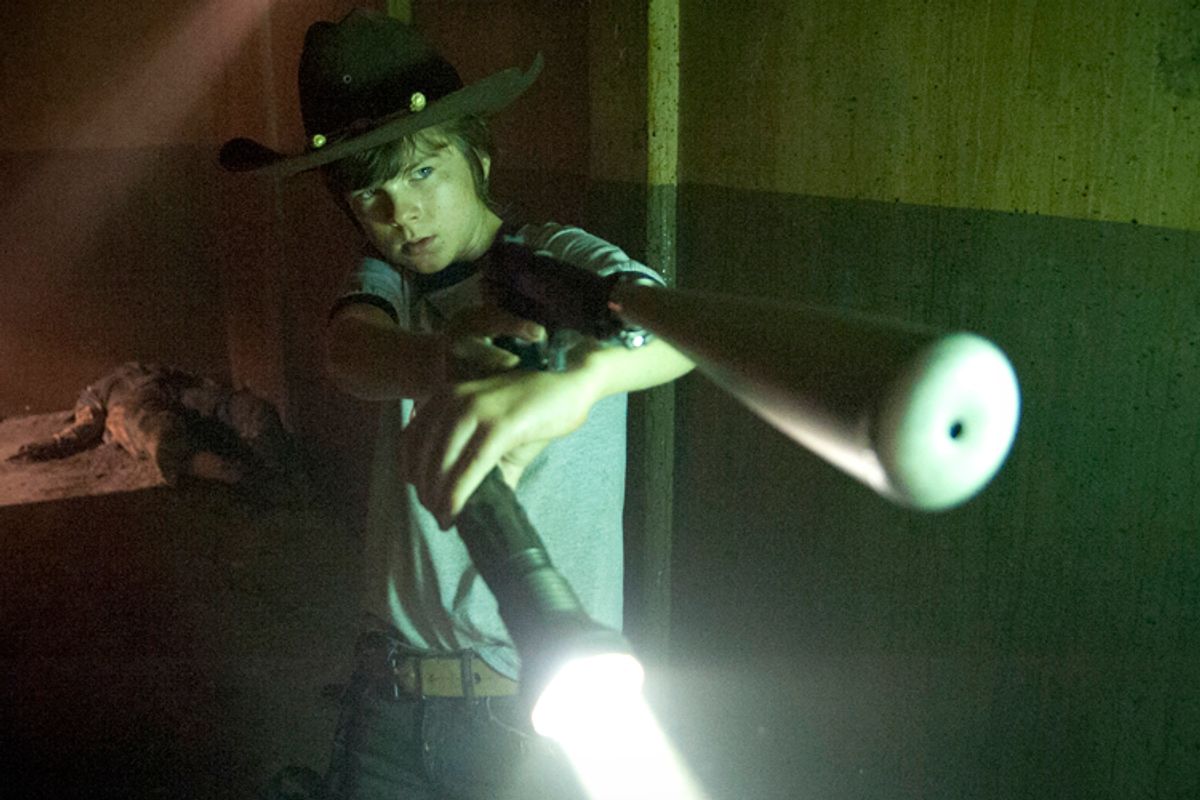

So what to make of the rise of child warriors in a culture desperate to keep children innocent? Neither bad seeds nor suffering victims, "The Walking Dead’s" Carl, "The Hunger Games’" Katniss, and now Ender Wiggin face death and win. They sometimes act violently in their own defense, and often do so without remorse. They are not innocent, but neither are they evil.

I suspect our current fascination with child warriors comes from the guilty knowledge they bring. For we already live in a terrifyingly dangerous world for children, as we’ve learned to our sorrow at Newtown, at Columbine, and in countless cities and towns where firearms kill children. It’s a particularly treacherous world for children of color. While parenting columns may choose to obsess over children’s access to sexual education, or the damage caused by mothers who lean in or opt out, there are a host of horrors facing American children that get a lot less hand-wringing. For Trayvon Martin, the trip to the corner store to buy candy was as dangerous as moving through a war zone. For eight-year-old Donald Maiden, the innocent child's pastime of tag was hazardous:a man shot him in the face on a whim. As Harvard historian Robin Bernstein contends, white American culture tends to construct childhood innocence along racial lines. The children who qualify for Eva’s saintly exclusion from the world’s sins, it seems, need to look the part of the pale angel.

So perhaps it’s no surprise that the current crop of child-warriors are white. If we depicted children of color frantically defending themselves against the world’s predations, we wouldn’t need to develop alternate worlds to accommodate them. We’d be looking at the news, and we’d be ashamed of what we’d see. For if Americans are prone to see blond children as angelic replicas of Little Eva, we are also way too liable to see an assertive black child as an inherently bad seed. We lock up brown and black children at a truly astounding rate, arresting children as young as six years old for temper tantrums. "The Walking Dead’s" riveting scene depicting children attacked in a dank prison block could find plenty of parallels in our own zombie-free world, where former schools turn out to be macabre graveyards, and where abuse of juvenile inmates is an epidemic.

So I, for one, welcome the recent rise of dystopic children and the death of innocence they herald. The innocent child-cherub was never a very good fantasy to begin with, especially for the children caught up in it. The emotional power of the innocent child comes at too high a price: they have to die to prove how much better they are than the world around them.

If we want a way out of this nightmare world, it can’t come from setting up certain privileged children as angels, and it can’t come from pretending that other children aren't already fighting for their lives. Just maybe, fictional kids like Carl and Katniss can allow us to see children as they actually are in our world--complicated human beings, who, like the rest of us, often have to make hard choices in a dangerous landscape.

Shares