The Internet hasn't really changed the form of the book that much, but the book review is another matter. Yes, you still sometimes hear pundits proclaiming that books need to get with the 21st-century program by including multimedia elements, but publishers now report that their tentative forays into "enhanced e-books" -- texts with additional video, audio or image files -- have not been a hit with readers. Instead, the e-book explosion of the past five years has been about innovations in distribution -- books that can be downloaded in a trice and stored by the dozens in slim, lightweight devices.

Meanwhile, the Internet, as everyone knows, has led to a staggering proliferation of reviewing; people craft elaborate (or cursory) critiques of everything from energy bars to bluetooth speakers, as well as books, art, music, film and television series, which can now be reviewed one episode at a time. Here is where an unanticipated creativity has flourished. If you had told any of us 20 years ago that we'd be amusing ourselves of an afternoon by reading parody reviews of ball-point pens written by total strangers, well, you'd have gotten some strange looks.

The most visible new kind of book criticism is the Amazon customer review. Because Amazon tightly controls the content of those reviews -- policing them for profanity, links to outside sites and other elements it deems inappropriate -- the reviews themselves aren't especially remarkable. Some are impressively articulate or dismayingly remedial, but it's mostly the open-to-all aspect of the forum (with the corresponding potential for abuse), as well as the averaging of starred ratings that gets remarked upon. Individual reviews matter less than the fact that multiple opinions are presented in the same place and can be added up or weighed against each other. That and the fact that for the first time, huge numbers of unpaid amateurs are getting the chance to weigh in on the books they read and to place the results before a potentially large audience, all, for worse but sometimes also for better, without having to account to an editor.

Goodreads, the massive social networking site for readers (purchased earlier this year by Amazon), offers its members more freedom than Amazon's product pages. In two earlier articles, I've chronicled the tensions flaring between authors and reviewers on Goodreads, a situation that led to the site's announcement this fall that it would begin actively deleting reviews that violate its terms of use. One thing that caught my eye among the many suggestions the site fielded while deliberating on this change was a complaint about form. According to Goodreads' Customer Care director, some users requested that "no GIFs should be allowed" in reviews.

I know, I know: To some of you the idea of using a GIF (for the uninitiated: a small, soundless animated image on a repeating loop) in a book review sounds bizarre. But the practice does flourish, if controversially, in some sectors of Goodreads' universe of book lovers, as well as in blogs and comments threads across the Web. In addition to the integration of GIFs into text reviews, other new reviewing techniques include liveblogging the reading of a book, in which responses are offered at various points before the critic gets to the end, and the back-and-forth dialogue between a reviewer and the people posting comments to her review. Sometimes the reviewer and commenters know each other well, so the comments elicit further explanations and you can see the reviewer's interpretation evolve or clarify. All of these innovations can be fascinating if you're interested in how people talk about the experience of reading.

With the exception (maybe) of comments-threads debates, most of these new styles of reviewing are also controversial. In a blog post a couple of months ago, Nathan Bransford -- a former literary agent turned author and popular blogger -- expressed horror at two GIF-heavy Goodreads reviews of "September Girls" by Bennett Madison, a novel Bransford had enjoyed. "Reviews like these demean and dehumanize authors," Bransford wrote. It's difficult to see why Bransford believes this, since (as many commenters would later point out) he chose two reviews that stick scrupulously to the contents of the book, quote abundantly from it for evidence and cast no aspersions on its author. Rather, the reviewers' reservations are ideological. "I really think this book hit on almost every way to demean a women," wrote one of them. "That is quite a feat considering I never thought I'd read a book that offended me more than 'Fifty Shades of Grey.'"

Whether or not Bransford agrees with this complaint, it's not flippant or gratuitous. However, I suspect that what shocked him was less the opinions of the reviewer than the way she delivered them. This notably included the use of GIFs and meme images to express disbelief and derision -- including the flat-lining display of a medical device to indicate how reading the book made her feel. Commenters who agreed with Bransford that the reviews in question were "over the top" and "just plain mean" singled out the use of GIFs and images as particularly outrageous and galling.

What's at issue here is a question of tone, and it's no surprise that it happened in the thriving subculture devoted to reading and writing YA books, where old-fashioned expectations of the special status accorded to published authors rubs up against a readership more inclined to treat everyone as peers. You would think that Bransford, someone enthusiastic about a novel in which one character refers to another character's girlfriend as a "dire pussy-web," would not be so flabbergasted by a review that speaks the same irreverent, profane language as both the book's characters and its intended audience. Is it really such a surprise that an Internet review of a book for and about teenagers should be written pretty much the way teenagers write stuff on the Internet?

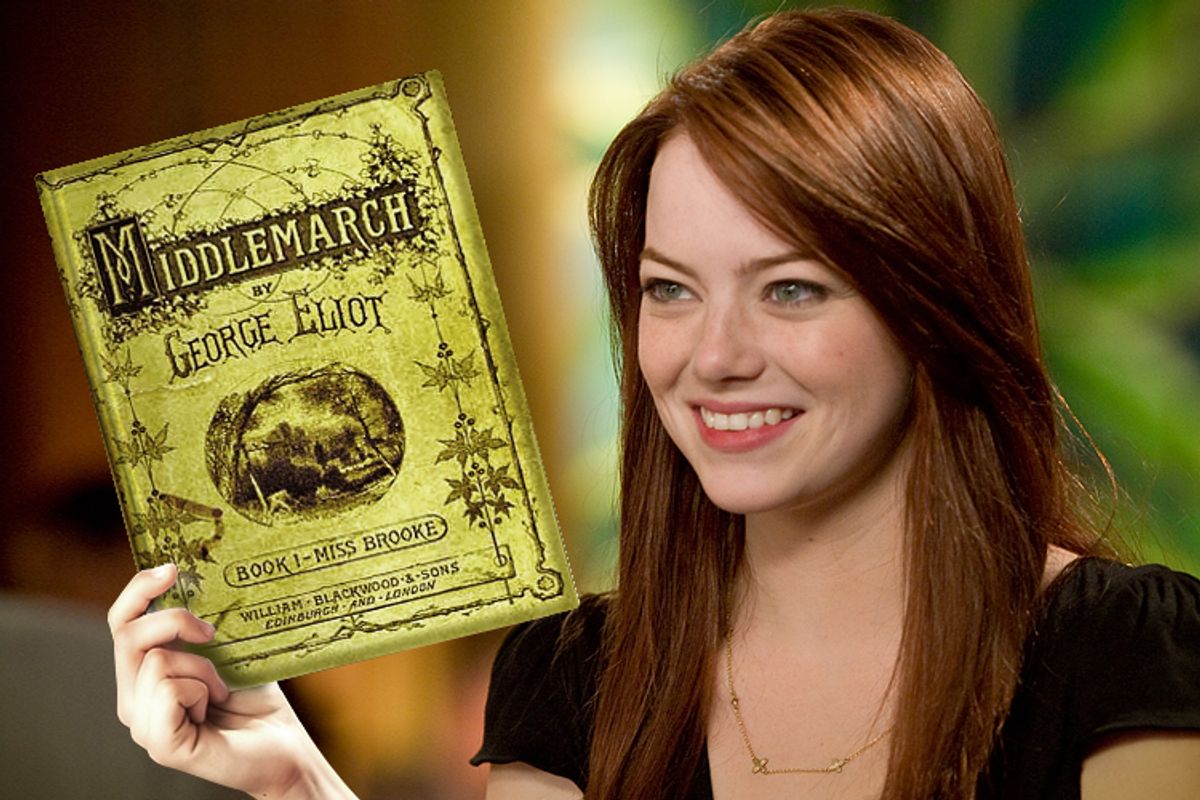

The GIFs and images used in the two reviews are, like the vast majority of visual elements cropping up in reviews and other critical discussions online, reaction GIFs: looped clips taken from commercially produced film and television, often featuring popular actors such as Emma Stone or Jennifer Lawrence rolling their eyes, gaping in astonishment, jumping with glee, shrugging their shoulders. They serve to underline the reviewer's point, rather than to make it, and they can come across as exaggerated and sarcastic, even bratty. But so what? It's not as if traditionally published professional book reviews haven't been equally harsh at times, and in this case, the reviews are highly attuned to their intended audience with its densely networked language of cultural references. Besides, as longtime Goodreads member Ceridwen (who doesn't use images or GIFs herself) explained to me in an email, "These reviews often use the very same critical tools found in professional reviews -- parsing of character and tone, close reading, comparison with other works or larger cultural positioning -- [but] there's no fiction of critical distance, and the emotional reaction is as important as the aesthetic one."

There are still some people dismayed by the linking of novels to the "ephemera" of popular culture, including some who believe that written culture exists on a more exalted plane than visual culture and never the twain should meet. In the artful Slaughterhouse 90210 tumblr, stills from television shows are juxtaposed with quotes from literary works: "Middlemarch" and "30 Rock" or Zadie Smith with "The Mindy Project." This is not so very different from, say, the astute comparison that James Hynes once made in the New York Times Book Review between the figure of God in "Paradise Lost" and Tony Soprano. Both are references that trigger a rich response with great economy, the kind of shorthand that's long been a conventional critical tool. If it's acceptable to liken Jennifer Egan's "A Visit From the Goon Squad" to Proust, then comparing, say, Walter White to Faust shouldn't be that much of a stretch. And if it's cool to do that in words, why should pictures be somehow beyond the pale? Would inserting a GIF of a glowering Tony Soprano instead of using his name have somehow cheapened Hynes' observation? I doubt it.

Reaction GIFs can seem canned (particularly if they've been used by many people, like a clip of Orson Welles clapping in "Citizen Kane"), but then so do certain shopworn reviewer's words like "compelling" and "poignant." A cliché is a cliché is a cliché. In the right hands, images can freshen a familiar sentiment ("I thought this book would be a lot more fun than it is"), as with a Goodreads review of Mark Danielewski's "The Fifty Year Sword" by karen, told almost entirely in photos. The same reviewer uses images to crack jokes or evoke a mood when discussing other books, much as the novelists W.G. Sebald and Carole Shields incorporated photos into their fiction and nonfiction -- a technique that, incidentally, never led anyone to label them less "literary."

Perhaps, though, what's unsettling about even the most inventive use of GIFs and images is the way they evoke emotion and subjectivity rather than ideas and analysis. They speak of the experience of reading rather than offering authoritative or finished assertions about what a book means. The critic's traditionally Olympian position as someone who knows more about the book than you do is also upended in the practice of liveblogging. Cleolinda Jones, whose hilarious liveblogging of Stephenie Meyer's "Twilight" novels have made her something of an Internet legend, has also live-tweeted George R.R. Martin's "Game of Thrones." "I got a lot of 'Oh, you sweet summer child'," she told me in an email, characterizing the response of friends familiar with the novel's startling plot twists.

Why would someone want to read a critic liveblogging a book they've already read themselves? Why welcome the insights of a person who very obviously knows less about the subject than you do? Jones, who also posts television recaps to her LiveJournal blog, explains that "watching someone new to a series recap or livetweet is a way of re-experiencing [it] … the same way you might look forward to handing down books to your kids or watching a favorite movie with them for the first time. … One of the great joys of art/entertainment is sharing and group experience." Reading a book, especially a work of fiction, is an experience that unfolds over a significant amount of time, with fluctuations in involvement and anticipation, changing feelings toward characters and a growing understanding of the text's meaning. Every reader goes through this process alone, but liveblogging becomes a way to communicate what it feels like as it's happening. It offers an intimacy rarely found in traditional book reviewing.

Chances are, though, that most people you know won't have read the book you're reading; books, apart from a few exceptions such as "To Kill a Mockingbird," just don't achieve the level of cultural saturation that film and television do. GIFs and images taken from familiar films and television have become a form of shorthand that often works best with criticism that makes a forceful argument, whether about monetary policy (yes!) or an academic's blithe remarks about how he never teaches woman writers. The GIFs themselves are not artful, which is not to say that they can't be used in artful ways, even though most GIF blogs and tumblrs serve as simple, succinct thumbs-up/down logs of someone's reading.

Which is not to say that GIFs can never be artful, because some are. They can be as lovely or profound as any other image

and the looping that seems to drive so many people crazy can carry its own significance. I found myself staring at this time-lapse sequence of a birthday candle burning

and thinking about certain novels, like Kate Atkinson's "Life After Life," that depict the way a human life consumes time, or vice versa. This GIF would be better with a less randomly cluttered background, but for me the repetition of the candle's disappearance suggests the perpetual replacement of one generation by another. OK, maybe that's just me, and not what the GIF's maker intended, but isn't that also a part of art's power, the way it acquires new meaning from every person who encounters it? Multimedia book reviewing is still in its infancy, but that doesn't mean it can't grow into a glorious adulthood.

Shares