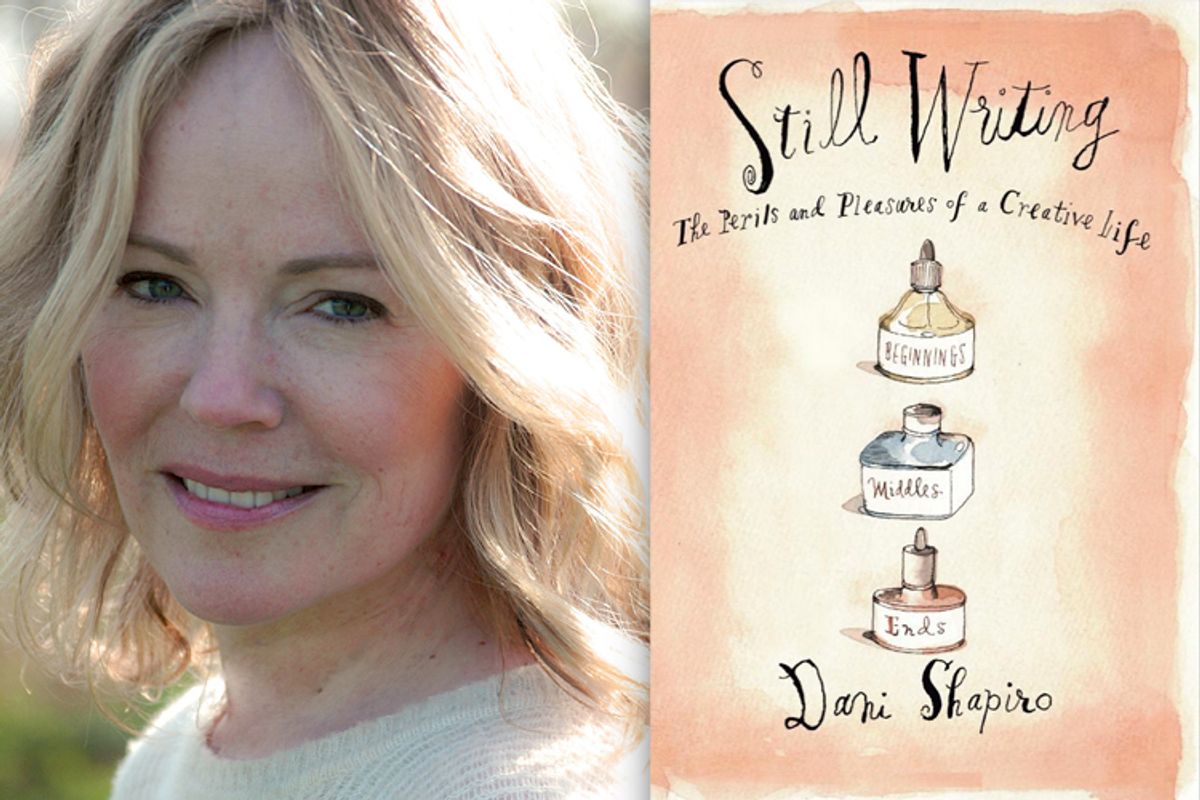

I’ve long been an admirer of Dani Shapiro’s bestselling fiction and nonfiction. Her memoir, "Slow Motion," was a source of inspiration when I was shaping my memoir, "History of a Suicide: My Sister’s Unfinished Life." Her new book, "Still Writing: The Perils and Pleasures of a Creative Life," is everything I would expect and more from a writer of Shapiro’s dedication, integrity and, yes, devotion (the title of her most recent memoir) to the art and craft of writing. It is warm, honest, forthcoming, insightful and intelligent. It’s a book that will provide inspiration and insight to new writers, and will be a comfort and companion to seasoned writers.

“Don’t think too much. There’ll be time to think later," she writes. "Analysis won’t help. You’re chiseling now. You’re passing your hands over the wood. Now the page is no longer blank ... Now you’ve carved the tree. You’ve chiseled the marble. You’ve begun."

What’s most amazing about "Still Writing" is how, through Shapiro’s grace and instruction, she makes the reader share her unswerving belief that the act of writing can transform and shape our vision of ourselves and of the world. I’m delighted to talk with her about the practice and art of writing.

I love how you open "Still Writing" with the image of being a girl hiding on the staircase without making a sound, young detective to the adult world of your parents, to explain the beginning of your literary education. Are you saying that writers must be spies? Could you elaborate further?

Writers are outsiders. Even when we seem like insiders, we’re outsiders. We have to be. Our noses pressed to the glass, we notice everything. We mull and interpret. We store away clues, details that may be useful to us later. In her beautiful essay “Outlaw Heart,” Jayne Anne Phillips writes that “the writing life is a secret life, whether we admit it or not.” She goes on to say that we are “unfailingly attracted to the secrets of others.” Now, I grew up in a house full of secrets. My parents kept the urgent and salient details of their histories from me –– and somehow, I knew this. And, knowing this, I became determined to unearth. To excavate. And I do believe that this need to know was the beginning of my becoming a writer -- though of course it took many years, and the light of retrospect, to understand this.

In a chapter called “Inner Censor” you write about a censor sitting on your shoulder when you write. This is fascinating. Do you think to be plagued with self-doubt is an occupational hazard for a writer? How do you push through?

I’d take it a step further and say that I’m not sure self-doubt is an obstacle. It might even be a writer’s best ally. It seems to me that every really good writer I know is plagued by it. Confidence is highly overrated when it comes to creating literature. A writer who is overly confident will not engage in the struggle to get it exactly right on the page -- but rather, will assume that she’s getting it right without the struggle. People often confuse confidence with courage. I think it takes tremendous courage to write well -- because a writer has to move past the epic fear we all face, and do it anyway.

As for pushing through, it helps to think of that inner censor as a beloved but annoying friend who has moved in for the duration. That friend is never going away. So you make peace with your inner censor. You say some version of, thanks very much for sharing, and then move on, past that censoring voice, and into your work.

It’s interesting to consider the landscape of literature before MFA programs and writing workshops became popular. As once a student of writing, and now a teacher of writing, do you think writing can be taught? What does it mean to have talent? Is there something to be gained for the writer struggling alone in the dark?

I’m of two minds -- more than two minds, actually -- about the professional degree for the writer. I mean, I have an MFA. And lots of people have them. And I’ve taught in MFA programs for many years. I do think there’s a lot that can be learned. Craft can be learned. And community is powerful. So are mentors -- and often, young writers end up with both colleagues and mentors who they first met in graduate writing programs. But there are so many factors that can’t be taught, and that only come -- if at all -- from a lifetime of sticking wth it. Of course, there’s such a thing as having a gift. But the gift is useless if the writer doesn’t have the muscles of persistence, patience, the ability to withstand the indignities and rejection inherent in the life of any artist. Gifts are nothing without endurability.

I’d be interested to hear you discuss the impulse behind writing fiction and memoir. For instance, what made you choose nonfiction as a form to ponder your ideas about faith? Couldn't that subject matter have been interesting terrain to explore in a novel?

In my experience, a book announces itself to me along with its form. I’ve never been in the midst of writing memoir and have had the thought: Oh, perhaps this should be fiction. Nor have I been at work on a novel and considered the possibility of turning it into memoir. This is true for me, as well, with stories and essays. Even with plays and screenplays -- I’m not a playwright or a screenwriter but I have had ideas that have presented themselves to me in these forms. (That just means those ideas never see the light of day.) In the case of my memoir "Devotion," it was clearly a memoir -- a spiritual memoir -- which I found completely disconcerting, as I’d never imagined I’d writer a spiritual memoir. But the material demanded to be explored -- and the way it seemed to ask to be explored was through using my history, as well as my current life, as a spiritual laboratory of sorts. I did something I’d always told my students not to do: I had no distance, no perspective. I had only my questions and a profound desire to explore them on the page.

I'm intrigued by the title of your new book, "Still Writing." As an editor, and also as a writer myself, I've often thought about the question of how many works a writer has inside him or her. It is curious, for instance, that two of our major writers, Philip Roth and Alice Munro, have announced that they no longer plan to write another book. How much of writing a novel or a memoir is predetermined by an individual's history? Or circumstances of life events? Or perhaps the two are not related.

I don’t think it’s possible to separate out the strands of a writer’s history, circumstances, life events, and that writer’s themes. In "Still Writing," I saw that theme is just a fancy literary term for obsession. We aren’t in control of our obsessions. That’s what makes them obsessions! And if we were to look at the body of work of any writer, we would see what drives that writer’s internal life. Whether our work is wholly imaginative or wholly based on memory, our internal lives are all we have to go on. As for the idea of retirement -- I don’t know what to think. Writing is hard. So hard. And perhaps after a lifetime of grappling with the page, it might feel good to just … stop. On the other hand, at least at this point in my own life, the thought of not writing fills me with dread, because it is the sole instrument through which I come to know my own mind. Without it, I think I might be babbling somewhere in a corner.

Writing is an enormous part of your life. "Still Writing" showcases a mind attuned to the complexity of the task, and also a mind interested in probing process. When did you know you wanted to become a writer? Is the initial impulse that propelled you to write your first novel still there when you attempted your other works? What is the trigger for you?

I knew I wanted to be a writer before I knew that being a writer was possible. It’s easier to see in retrospect. I look back now at the girl I was -- a voracious reader, the kind who reads beneath the covers with a flashlight, and an avid writer of letters that were full of fantasy and invention -- at the time I wondered if there might be something very wrong with me. I secretly feared that I was a pathological liar. But in fact I was living in my imagination, which was something for which I had no permissible form. I was raised in an Orthodox Jewish family, in a New Jersey suburb, and I didn’t know artists or writers. I simply didn’t know it was possible. It wasn’t until I got to Sarah Lawrence and started to see real live working writers in the flesh -- Grace Paley was a teacher of mine, and just watching her commute up from the city, and teach her workshops, and meet with students who sat on pillows on her office floor … that sense of a life as a writer/teacher/wife/mother/activist (she was always getting arrested for civil disobedience – you’d come to class and find a note tacked to the door: Grace is in jail) gave me my first window into the possibility of a different kind of life.

As for triggers, with each book it’s different. In the case of "Still Writing," people kept assuming I was writing this book -- because I have a blog about the creative process that had attracted lots of readers -- but I had no intention of doing this kind of book. In this case, it was more like I was asked to do it. In the case of "Devotion," it was the trigger of an intense emotional/existential midlife crisis. In my novels "Family History" and "Black & White," I had questions I wanted to try to explore – about motherhood, about the responsibility of the artist, about parental anxiety. Actually, in "Black & White," place was a huge trigger. I didn’t find my way into that novel until I understood its precise landscape, which was a rent-controlled apartment on the 12th floor of the Apthorp, a building on Broadway and 78th Street in New York City. Once I had that apartment, everything became clear.

In his play "After the Fall," Arthur Miller wrote, “Why is betrayal the only truth that sticks?” Is writing a form of betrayal? As a writer who has written personal memoir, how do you negotiate the fine line between privacy and disclosure and its service to art?

This question continues to arise again and again, doesn’t it? I imagine you have struggled with it as well, Jill, in your lucid memoir about your sister’s suicide. I have written about my parents quite a lot -- particularly my mother. When she was alive, it was a constant struggle between us. She fought me, and was enraged at me for having a voice, period. She had wanted to be a writer herself, so the fact of my life was an affront to her. (Another parent might have been proud, but that’s the way it was.) After her death, I thought it would be easier, but I discovered that, in fact, it was more difficult for me to write about my mother because now I got to have the last word. I found that very painful, and challenging. And a tremendous responsibility. I wrote about it in an essay called “Evil Tongue” that was published in Ploughshares last year. In Jewish scripture there is a great deal written about something called “Lashon Hara,” which translates to “Evil Tongue.” It’s believed to be a grievous sin to speak ill of another -- or, pretty much, to speak of another at all. I try to be aware. To come from a loving place, hokey as that may sound, even when that loving place may be one that stings. I try not to be a monster. The place where this matters to me most is regarding my son, and my husband. I will not violate their privacy. Fortunately, they both don’t mind being written about -- but there are places I won’t go. It’s not worth it. And if that makes me a lesser artist – so be it. These relationships are so hard-won for me, I won’t take the chance of either one of them turning to me and saying, I wish you hadn’t written that.

Picasso said that "Art is the lie that tells the truth." John Dufresne, one of my authors at Norton, has written an insightful book about fiction writing titled "The Lie That Tells the Truth." As both a novelist and a memoirist, and now having written a book about writing, I wonder if you might address the topic of truth in fiction and nonfiction. Do you think one form gets at the truth in a different way than another? Is writing fiction more liberating if indeed fiction is inspired by an autobiographical event? Or vice versa?

It’s funny -- when people who have read my memoirs suggest to me that I must feel terribly exposed, I often think that my fiction -- all of our fiction -- is much more exposing. Memoir comes from a more conscious place. Assumedly, we know what happened, and we’re trying to piece together a story out of what happened, to come, perhaps, to a deeper understanding. The art in memoir is more associative than deeply subconscious. If I can make that distinction.

In fiction, the subconscious is paramount. We are driven -- we follow the line of words. Our secret lives, our desires, our obsessions, our fears, shape every line, whether that fiction is autobiographical or not. I sometimes have the feeling, after visiting a class or a book group that has read a number of my novels, of having just participated in some really intense group therapy. Metaphors and thematic through lines are pointed out to me, and all I can do is nod, speechless. So I think that fiction gets at the truth in a more subterranean way, hidden from the writer in a way that it isn’t in memoir.

In "Still Writing," you have a chapter called "Trust," where you write about the need for readers at a certain point in the creative process to show work to another reader. You wrote that your husband is your first reader. When do you know when your work is ready to show to a first reader, or to an editor? Do you feel that creative work can benefit from editors? Have you ever had an experience where you regretted showing work to an editor? And finally, how do you know when to trust what a reader or editor is telling you?

Would it be a cop-out to say I think this changes with every book? I’ve written books that have benefited from outside readers all the way through the process. And other books I felt I couldn’t show any of until I was very far along, if not finished with a first draft.

My readers change with each book, depending on the needs of that book — I try to choose writer and editor friends who will be at once sympathetic to the form and subject matter, and at the same time, critically discerning. My husband is the only through line for me in all of this. I will often read work aloud to him when it’s in process. This is because I feel tremendously safe, I know he wants only the best for my work, and we’re really in it together.

I once showed pages of a novel too early to someone in my professional life, and I regret having done so. It sidelined a novel that I’d been loving working on. Now, it’s possible that this person saved me time — that the book really wasn’t working. But I remain with the sense that it was my own insecurity and anxiety that had me showing it too early — and I’m still not sure I was right to put it aside. But I felt I had lost the magic.

Cynthia Ozick says this great thing in an old Paris Review interview about talking about the work too soon: “I have lost stories,” she says, “and many starts of novels before. Not always as punishment for 'telling,' but more often as a result of something having gone cold or dead because of a hiatus. Telling, you see, is the same as a hiatus. It means you’re not doing it.” I love that. When I share work too soon, or talk about it too much (or really, at all) it’s dangerous. But just because I know better doesn’t always mean that I practice what I preach.

You’ve written several novels and memoirs and now a writing book. What’s next?

After my answer to the last question, is there any way I can possibly answer this one? No. Not another word out of me.

Shares