The government’s multi-billion-dollar effort to clean up the nation’s largest nuclear dump has become its own dysfunctional mess.

The government’s multi-billion-dollar effort to clean up the nation’s largest nuclear dump has become its own dysfunctional mess.

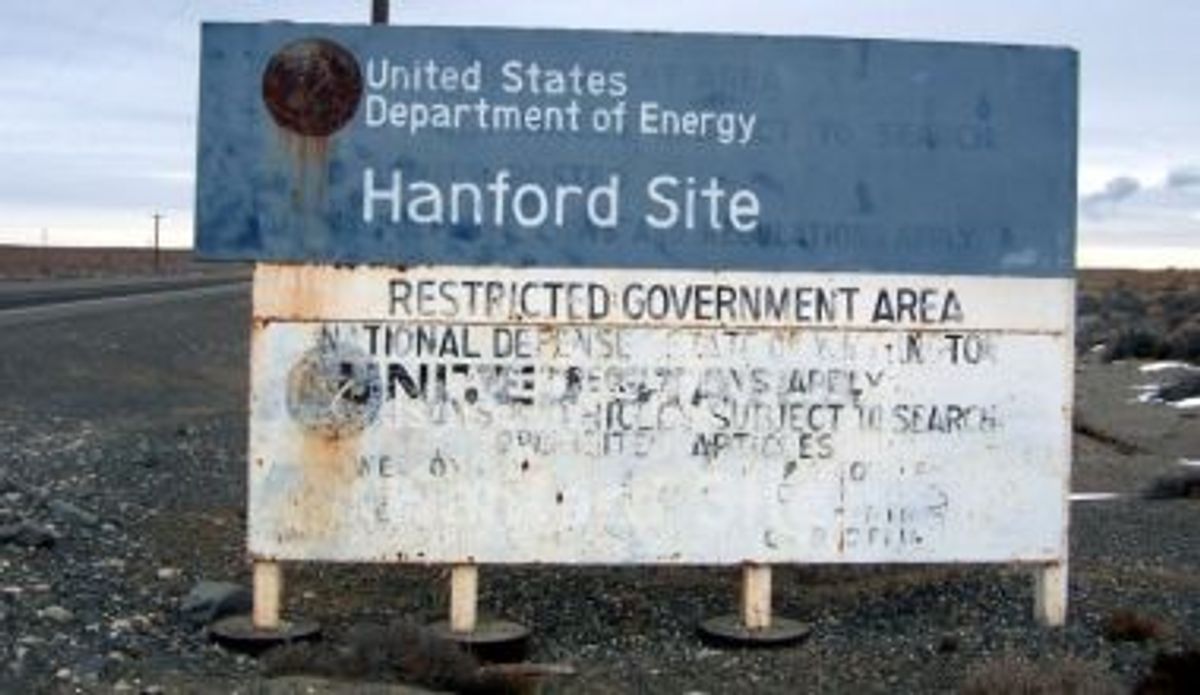

For more than two decades, the government has worked to dispose of 56 million gallons of nuclear and chemical waste in underground, leak-prone tanks at the Hanford Nuclear Site in Washington State.

But progress has been slow, the project’s budget is rising by billions of dollars, and a long-running technical dispute has sown ill will between the project’s senior engineering staff, the Energy Department, and its lead contractors.

The waste is a legacy of the Cold War, when the site housed nuclear reactors churning out radioactive plutonium for thousands of atomic bombs. To clean up the mess, the Department of Energy (DOE) started building a factory 12 years ago to encase the nuclear leftovers in stable glass for long-term storage.

But today, construction of the factory is only two-thirds complete after billions of dollars in spending, leaving partially constructed buildings and heavy machinery scattered across the 65-acre site, a short distance from the Columbia River.

Technical personnel have expressed concerns about the plant’s ability to operate safely, and say the government and its contractor have tried to discredit them, and in some cases harassed and punished them. Experts also say that some of the tanks have already leaked radioactive waste into the groundwater below, and worry that the contamination is now making its way to the river, a major regional source of drinking water.

Some lawmakers say Hanford has been an early — and so far dismaying— test of whether DOE Secretary Ernest Moniz, previously an MIT physics professor, can turn the problem-plagued department around through improved scientific rigor and better management of its faltering, costly projects. They have accused his aides of standing by while a well-known whistleblower was dismissed last month.

Meanwhile, DOE officials are considering spending an extra $2 billion to $3 billion to help the plant safely process the waste. Doing so could delay the cleanup’s completion for years, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) estimated in December.

In an Oct. 9 letter, Sen. Edward J. Markey, D-Mass., demanded that Moniz take new steps to ensure that the project’s technical experts are well-treated. Four organizations have reviewed their complaints, he said, and “all have agreed that the project is deeply troubled, and all have affirmed the underlying technical problems.”

On Nov. 14, Sen. Ron Wyden, D-Ore., said at a confirmation hearing for DOE’s general counsel that he worries “the message is out department-wide that when you speak truth to power and come forward and lay out what your concerns are, you face these kinds of [retaliation] problems.” If that’s true, Wyden said, “I think it’s going to be very detrimental to the safety agenda.”

A troubled past

Government officials and environmental activists agree that Hanford needs to be cleaned as soon as possible. But the timetable keeps slipping: Almost 25 years ago, DOE, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and the state of Washington agreed to start turning the waste into glass by 2011.

But in 2010, the deadline was extended to 2019, with a completion date of 2047. Moniz announced last month that the agency is likely to miss three more project deadlines. Meanwhile, the estimated cost of cleaning up Hanford ballooned from $4.3 billion in 2000 to $13.4 billion in 2012, according to GAO.

On Sept. 30, DOE’s inspector general Gregory Friedman issued an audit stating that Bechtel, the project’s prime contractor, repeatedly made design changes to plant equipment without a proper safety review, a problem Friedman called “systemic.” DOE’s Office of Environmental Management responded that Bechtel has begun addressing these shortcomings, and promised to monitor the company’s actions.

The report came 13 months after Gary Brunson, then DOE’s plant engineering division director, told superiors in a memo that Bechtel had made at least 34 technical decisions that were incorrect, infeasible, unverified, unsafe or too costly, according to a copy. Frank Russo, Bechtel’s plant director at the time, responded that the issues were not new and had all been addressed in concert with the department.

In addition to the cost increases, construction delays and critical reports, employees and independent agencies have said DOE and contractor officials overseeing the project created a workplace climate that discourages employees from raising technical and safety concerns.

They say that project supervisors have relentlessly pushed over the past two years to shorten testing and “close” technical issues by deadlines, meeting their benchmarks to gain financial rewards, even though the problems are not fully resolved. A DOE spokesperson, Carrie Meyer, responded that “closing” a problem only means that a decision has been made to move forward with a credible solution.

The most prominent of the plant’s whistleblowers is Walter Tamosaitis, the project’s former research and technical manager for URS, the prime subcontractor to Bechtel.

Tamosaitis’s troubles began after a 2010 meeting with Bechtel and URS managers, at which he turned over a list of technical issues that he said could affect plant safety, including continuing uncertainties about how the wastes should be kept mixed to stop them from settling into a critical mass and causing a chain reaction. If that happened, the resulting explosion would release deadly radiation.

Two days later, on July 2, URS, acting under orders from a Bechtel executive, pulled him from the project, according to a federal court complaint Tamosaitis filed in November 2011. He was reassigned to a basement office and stripped of supervisory responsibilities.

The complaint includes an e-mail written by Russo of Bechtel on June 30 to the company’s president that “a clear way to kill momentum within the project and with Congress re funding would be to declare m3 [the mixing issue] as not complete.” The next day, he wrote another e0mail saying, “Declare failure and high probability that the $50 mil goes away.”

Bechtel engineering managers said they would consider improving the design once the issue was closed, Tamosaitis said in his legal complaint. “They were trying to justify their design,” Tamosaitis said, “but their design led to safety issues.”

Similar disputes recurred repeatedly that spring, as management officials struggled to meet their deadline. On June 16, Perry Meyer, a Pacific Northwest National Laboratory scientist at the time who now works for the safety board, wrote an email for the record relating “three potential threats I have heard” from managers toward technical staff.

Tamosaitis’s federal court complaint includes emails that show Russo ordered his removal July 1 after communicating with Dale Knutson, DOE’s project director of the plant at the time. “Use this message as you see fit to accelerate staffing changes,” Knutson said in an email to Russo.

Russo, after receiving Knutson’s email, sent a message to URS plant manager William Gay, stating that “Walt is killing us. Get him in your corporate office tomorrow.” Gay responded, “He will be gone tomorrow.”

Bechtel and URS have denied allegations of retaliation, stating that Tamosaitis was already scheduled to be reassigned because his job was coming to an end. Tamosaitis had prior performance issues and he sent an inappropriate and inaccurate email to project consultants, Bechtel has said in court filings.

But after Tamosaitis complained to the department’s nuclear safety board, it affirmed in a June 2011 report that his removal “sent a strong message to other …project employees that individuals who question current practices … are not considered team players and will be dealt with harshly.”

After Tamosaitis’s forced departure from the plant, he was assigned to URS’s main office in downtown Richland. Then, last month, URS managers told Tamosaitis — a 44-year company veteran with a Ph.D. in engineering — to clean off his desk and leave that day. URS insisted — as a condition of receiving severance pay — that he give up the lawsuit he filed against the company. He refused.

In an interview with the Center, Tamosaitis, 66, said the layoff was “clearly retaliatory.” Tamosaitis said he was particularly surprised by URS’s decision, because three months earlier, he had met with Moniz to discuss his concerns about the plant’s design and safety culture. Moniz had promised at his April confirmation hearing to meet whistleblowers at Hanford.

Tamosaitis was also encouraged by a memo Moniz sent to department heads in September stating DOE must “foster a safety conscious work environment” that does not “deter, discourage, or penalize employees for the timely identification of safety, health, environmental, quality or security issues.”

After Tamosaitis’s dismissal, Markey and Wyden, D-Ore., each sent angry letters to Moniz stating that it appears little has changed. Tamosaitis’s “termination within days of your pledge can only be seen as perpetuating a culture that would plunge DOE employees and contractors who dare to raise safety issues into the deep freeze,” Wyden wrote in his Oct. 9 letter.

DOE officials did not respond to requests by the Center for comment about the letters or the dismissal. Wyden spokesperson Keith Chu said Moniz has not replied to the senator’s letter.

Blum said in an emailed statement that, “While we will not comment on specific employee matters, in recent months URS has reduced employment levels in our federal sector business due to budgetary constraints.” The company, she wrote, “encourages its employees to raise concerns about safety.” She also said URS asks all laid-off employees to sign severance agreements absolving the company from legal claims.

Other technical managers have also alleged retaliation for expressing safety concerns. Donna Busche, a URS employee and the plant’s manager of environmental and nuclear safety, filed a lawsuit against Bechtel and URS in February claiming the companies treated her as a “roadblock to meeting deadlines.” URS and Bechtel officials excluded her from meetings and belittled her authority, she alleged. The companies deny it.

Busche said her troubles escalated after she questioned DOE’s judgment at an Oct. 7, 2010, safety board hearing about how much radiation might escape in the event of an accident at the plant. Board officials had expressed concern that DOE’s calculations may underestimate the threat, but Ines Triay, then DOE’s assistant secretary for environmental management, defended the calculations.

When a board member asked Busche if she supported DOE’s method, Busche replied, “Short answer, no,” according to a transcript of the hearing. Afterward, Triay told Busche if her “intent was to piss people off, [she] did a very good job,” according to Busche’s complaint.

Triay, now executive director of the Applied Research Center at Florida International University, did not respond to requests for comment.

Tom Carpenter, executive director of the Hanford Challenge, a nonprofit in Seattle that has assisted Hanford whistleblowers, said URS “created the conditions” to lay off Tamosaitis. “He was turned into a symbol by them that this is what happens to people who raise concerns,” Carpenter said. “It’ll be a cold day indeed when someone tries to follow in his footsteps.”

Cleaning up the mess

In August 2010, the department announced that the mixing issues were closed. As a result, Bechtel and URS received more than $4 million in bonus funds. Congress also allocated $50 million in additional annual funding for fiscal years 2011 and 2012, according to GAO.

But problems persisted. In 2011, DOE scientist Don Alexander expressed new concerns that the mixing vessels could erode and spring leaks. Last year, the department halted construction on key parts of the plant as it worked to resolve technical problems, including ensuring that the wastes will be adequately mixed. Alexander said DOE and contract officials are planning full-scale tests of mixing vessels.

Bechtel spokesperson Jason Bohne said in a statement that Bechtel’s “focus remains on safely designing and building the Waste Treatment and Immobilization Plant to the highest nuclear safety standards. We remain committed to working with DOE to achieve the permanent solution for Hanford’s aging tank waste.”

In Sept. 24 report, Secretary Moniz told Washington State officials that officials want to start encasing some low-level waste in glass while resolving other problems with the high-level waste treatment.

Tamosaitis meanwhile says he is sorting through his papers and figuring out what to do next. “I want an environment where the foot soldiers can raise issues without fear they’re going to be put in a basement office for 16 months and then laid off,” he said. “This issue is a heck of a lot bigger than me.”

The Center for Public Integrity is a non-profit, independent investigative news outlet. For more of its stories on this topic go to publicintegrity.org

Shares