“Meet the last tribes on earth, before they pass away,” reads the invitation on one of the rotating slides greeting visitors to the website of photographer Jimmy Nelson. The text fades to lay bare the image of three Himba women, backs to the camera, one carrying a young child. “Feel their breath, smell their presence, touch their souls,” reads the text placed over the photograph of a Kazakh man posing with an eagle. “Hunters, fighters, nomads, Jimmy Nelson enchanted them all,” proclaims a slide featuring a fur-clad Chukchi man gnawing on a bone while holding a knife. Each destination, the text seems to imply, served up a bed of snakes to be charmed.

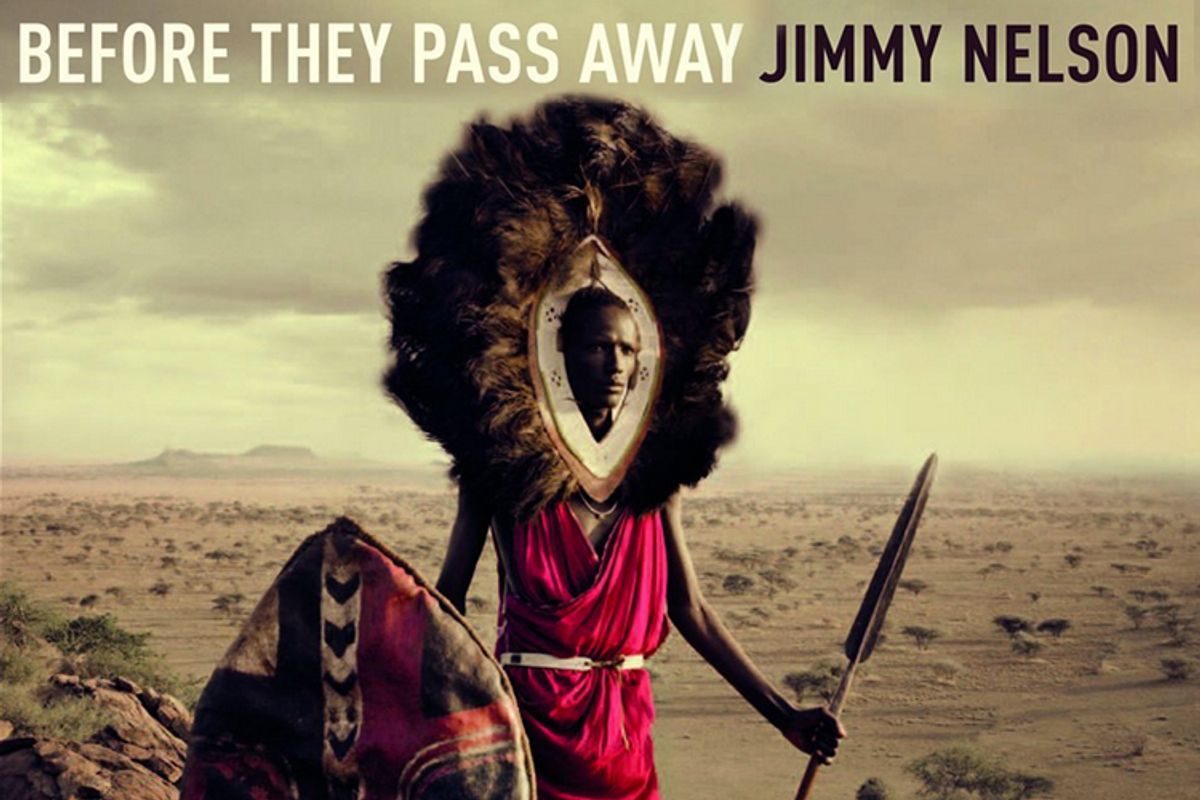

Nelson’s website is devoted to the promotion of his new book, "Before They Pass Away" (TeNeues, October 2013), which features 402 color photographs of the people among whom Nelson traveled. Nelson spent three years among 30 indigenous communities, including the Huli of Papua New Guinea, the Chukchi of Russia and the Samburu of Kenya.

The photographs are aesthetically exquisite, with vibrant hues, stunning landscapes, rich textures and gripping portraiture. But the artist’s discussions of his work are troubling.

Nelson’s website presents a portrayal of an explorer who “found the last tribesmen and observed them” and an artist who serves as “the last visual witness of flawless human beauty.” While these words have a romantic resonance, Nelson’s mission is built on a horrifying assumption: that these indigenous peoples are on the brink of destruction. He couldn’t be more wrong.

The Māori people, featured in Nelson’s book, make up 15 percent of New Zealand’s total population, and the 2012 census estimate of 682,100 Māori residents is part of a consistent upward trend. Seven seats of the Parliament of New Zealand are designated as Māori. Their communities have been impacted by colonization and the resulting warfare, disease, land loss and assimilation. But, although contact brought changes, far from being erased, the Māori people continue to thrive.

Nelson approached his subjects with a predefined notion of indigenous authenticity, which doesn’t align with the realities that have faced indigenous communities since time immemorial. In an interview with CNN.com, Nelson says that he grew up in Nigeria, Sierra Leone, Gabon and Cameroon, and feels that Africa “has lost the majority of its ethnicity and authenticity. … [W]hat I saw in my childhood is not there anymore." Similarly, Nelson told Time that he chose to leave out North American tribes because they haven’t retained their heritage. To critique the “authenticity” of another culture from the outside is a dangerous practice, and Nelson’s evaluation of communities during his lifetime fails to account for the flux experienced over thousands of years. Too often, onlookers expect indigenous peoples to remain static for the entirety of their existence, failing to consider their long histories of change before contact with outsiders.

The questioning and judgment of indigenous authenticity often have their roots in appearance. By treating people as art, Nelson plays into this notion. In his photos of the Kalam people of Papua New Guinea and Indonesia, headdresses, necklaces and body ornamentation serve as visual representations of identity. Besides Nelson’s written descriptions of each group he photographs, visual cues are all we can use to form our understanding. He calls himself a “collector of truth,” but how much truth can fit into a work rendered in two dimensions, telling visual stories curated by an outsider? Personal strongholds of identity are often invisible.

Nelson’s publication of "Before They Pass Away" is reminiscent of Edward S. Curtis and his series "The North American Indian." Beginning in the 1890s, Curtis took more than 40,000 photographs of North American Native peoples. While Curtis has been celebrated for his visual documentation of peoples and ways of life that are said to be gone, he is criticized for his manipulation of shots and subjects. Around 1910, he retouched a photo of Little Plume and his son Yellow Kidney, two Blackfoot men, to remove an alarm clock Curtis thought to be inconsistent with the otherwise traditional image.

In interviews, Nelson frequently cites Curtis as an inspiration for his work. Curtis’s posing of his subjects is treated as a scandal, but Nelson freely admits to the New York Times, “I directed the majority of the pictures, which Curtis also did.” While the people Curtis photographed often appear in their finest ceremonial attire, Nelson continues, “And 80 percent of the people I photographed are dressed as they do daily. About 20 percent are in their Sunday best.”

Curtis made significant contributions to the tribes he photographed by documenting points in their histories. In 1910, he photographed my great-great-grandmother’s half-sister, Virginia Miller, or Whylick Quiuck, with her canoe. He also recorded her account of the hanging of her father, Tumalth of the Cascades, by the U.S. government. Just a year earlier, the young Cascade chief added his signature to the Kalapuya Treaty of 1855. Virginia’s story of false accusations that led to her father’s death would have been lost without Curtis’s documentation. This is an important piece of the history of the Cascade people and of my family.

Although Curtis’s body of work stands as a contribution to tribal histories, he may have done just as much to further the notion of Native peoples as a vanishing race. According to Timothy Egan’s recent Curtis biography "Short Nights of the Shadow Catcher," in 1907, Curtis wrote in a photo caption, “The thought which this picture is meant to convey is that the Indians as a race, already shorn of their tribal strength and stripped of their primitive dress, are passing into the darkness of an unknown future.” Of the Hopi, he wrote, “There won’t be anything left of them in a few generations and it’s a tragedy.” More than a hundred years later, the Hopi people continue to live in Hopituskwa, where they have retained their culture, religion and language.

Curtis’s photographs have been essential to the world’s current conception of Native Americans, but he was only one of many artists who romanticized what they saw as the annihilation of the Indian way of life. In 1829, John Augustus Stone’s wildly popular play “Metamora; or, The Last of the Wampanoags,” depicts its eponymous Native hero as a bloodthirsty menace who was justifiably removed by the brave men who would fill the continent. Other depictions of indigenous vanishing would follow, most notably “The Last of the Mohicans,” an 1862 novel by James Fenimore Cooper that has been adapted for American film seven times. Even “Dances with Wolves,” a film lauded for its depiction of the Lakota Indians, ends with the scrolling text, “Thirteen years later, their homes destroyed, their buffalo gone, the last band of free Sioux submitted to white authority at Fort Robinson, Nebraska. The great horse culture of the plains was gone and the American frontier was soon to pass into history.”

In an interview with Roads and Kingdoms, Nelson says that Curtis “made the definitive document of the last tribes of North America.” To say that Curtis’s collection of photographs is definitive is to say that nothing more needs to be said about Native Americans, cementing tribes in a moment decided upon by a community outsider as the point after which the culture ends. The work of Edward Curtis looms large enough in the American imagination that it’s too easy to believe in a golden age of Native peoples. The rest of us that follow are thought to be watered-down versions of the real deal, but in truth, Native nations continue to change as they have for more than ten thousand years. Tribal historians and Native artists continue to produce work that contributes to tribal knowledge. Matika Wilbur, a member of the Tulalip Tribes, is currently at work on Project 562, a photo project dedicated to photographing Native North America, with a goal of unveiling the essence of contemporary Native issues and the magnitude of tradition.

Curtis hoped that his project would have an impact on the tribes he photographed. “I want to make them live forever,” he said, according to Egan. Similarly, Nelson told the New York Times that the developed world is “trying to find balance,” while “tribal peoples, in many cases, have the balance already, though they’re not necessarily aware of it.” He plans to return to the communities he photographed, show them the images, and “illustrate the importance of what they have.” It seems unlikely that these sophisticated indigenous communities might need life advice, since each has a notion of balance that has endured over millennia. And balance is not innocence or primitivism; it requires adaptation to external pressures. Although Nelson fears that indigenous communities “will all soon have internet and mobile telephones, and they will all become homogenized through the information that they receive,” it’s not his place to decide whether these technologies belong there or not.

Perhaps, despite Nelson’s gestures toward the good of the tribes, his labor of love really embodies the developed world’s search for meaning. “If they pass away, a part of ourselves will, too,” Nelson’s website laments, advertising “photographs of painted bodies, pure spirits, and free souls.” Onto these bodies, we might place our desires; through these souls, we can channel our search for identity, liberation and meaning. Over 464 pages, Nelson indulges our hoarding proclivities with a catalog of all the peoples he tells us will pass away soon: “Look mankind in the eye, before he disappears forever.” Is this fear of the disappearance of indigenous communities, on some level, a fear of more widespread destruction? If so, we can learn from the peoples of Nelson’s projects — not only their images, but their histories and current situations. Such peoples as the Maasai and Māori serve as tremendous examples of resilience in the face of encroachment and hardship. So many indigenous peoples have lived through the near-ends of their worlds. You can count on the tribes in Nelson’s book surviving the cell phone.

Shares