One of the greatest myths about American politics is that there was once a golden age of bipartisanship in which responsible, enlightened statesmen set aside partisan differences in order to collaborate with their colleagues on the other side. This understanding of history underlies constant calls for “grand bargains” among left and right on the budget and other issues. It also permits figures like Ross Perot and Michael Bloomberg to pose as practical problem-solvers superior to petty partisan politicians.

Like most historical myths, the myth of bipartisanship is a poor guide to historical understanding and contemporary action.

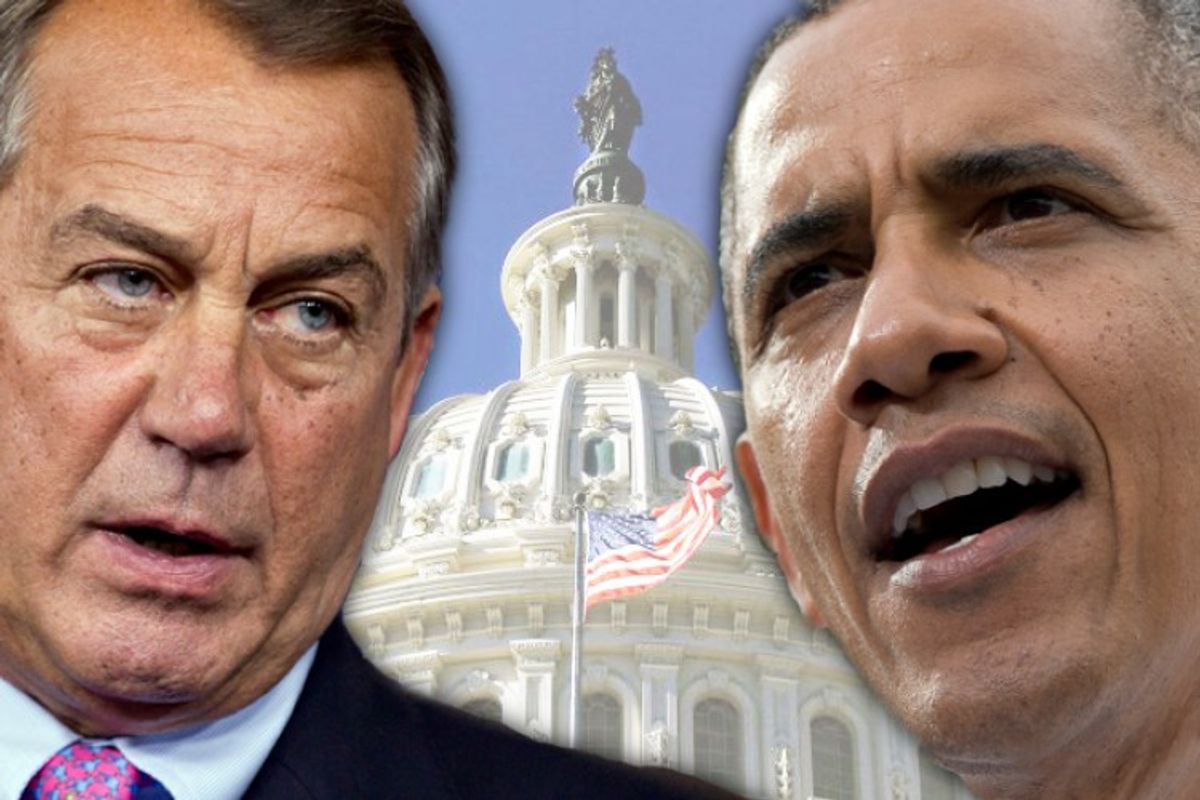

Yes, bipartisanship was much higher in the mid-twentieth century than it is now. A new graphic provides a striking illustration of the ideological fissioning of Democrats and Republicans in the U.S. Senate.

But while partisan polarization was lower in the past, ideological polarization—disagreements on the basis of philosophy and values—has always been high. Back in the bipartisan Fifties, there were plenty of conservatives who thought that liberals were communists and plenty of liberals who thought of conservatives as fascists.

The difference between 2013 and 1963 is that in the earlier period liberals and conservatives were found in both of the two parties, which still reflected the geographic realignment that had produced the Civil War. The Democrats, still based in the South, had their conservative Southern and Midwestern members, while the Republicans, still the northern party of Lincoln, had many liberal members.

Thanks largely to the political realignment caused by the Civil Rights revolution a century after Appomattox, the Civil War party system has been replaced by our present pattern, in which the Democrats are a largely urban and nonwhite party strongest in the North, while the GOP is dominated by white Southerners. As a result of the post-Sixties realignment, conservatives are no longer divided into two parties by memories of the Civil War and progressives have regrouped into a single party, the Democrats.

But the shift is less dramatic when we look at ideology rather than partisanship. Half a century ago, conservatives and liberals were at odds, just as they are today. The only difference is that each camp frequently collaborated with their philosophical soulmates in the other party.

For example, between the mid-term elections of 1938 and the late 1950s, a “conservative coalition” of right-wing Democrats and conservative Republicans dominated Congress, rolling back some New Deal reforms and blocking further liberal advances.

Liberals, too, worked with each other across party lines. For example, many Northern progressive Republicans voted alongside liberal Democrats for civil rights laws that were opposed by many conservative Southern Democrats.

This kind of bipartisanship among politicians who share the same ideology would be pointless today, now that the left is in one party and the right is in another.

And even at the height of cross-party coalitions, liberals and conservatives battled, just as they do today. While like-minded Republicans and Democrats often voted together, the kind of “grand bargain” or “compromise” dreamed of by today’s pundits—deals among liberals and conservatives, of any party—have always been extremely rare.

Even at its peak, then, bipartisanship was never an alternative to ideological conflict. And it was a temporary aberration, which came to an end with the ideological sorting of the two parties in the last generation. The replacement of two highly divided parties by two more consistent parties is a return to the norm in American history, when national parties have often disagreed about most issues.

Among other things, the demise of bipartisanship means a return to the typical pattern of political change in the U.S. Major reforms have never emerged from split-the-difference compromises among the major parties. Usually one party pushes through a major reform, over the opposition of the rival party but sometimes with the help of some rival-party politicians. The defeated party rails against the innovation for years or decades, but eventually accepts it.

Before the Civil War, the Jacksonian Democrats, supporting a smaller federal government, didn’t compromise with Whig proponents of a strong, active federal government. They defeated the Whigs and destroyed the Second Bank of the United States. The Whig party collapsed.

Following the Civil War, the dominant Republicans did not hesitate to demonize the Democrats as the party of secessionist traitors, as they rammed through their agenda of permanently abolishing slavery, federal support for railroads and high tariffs to protect American industry.

We are now in such a period again. The Affordable Care Act was inspired by conservative proposals, including “Romneycare” in Massachusetts and the right-wing Heritage Foundation’s health care plan of the 1990s. Nevertheless, it was overwhelmingly opposed by Republicans in Congress, who having failed to stop it have sought to repeal or sabotage it.

As well they should, if they believe their own ideology. Today’s conservative Republicans live in a different intellectual universe than today’s progressive Democrats. In the alternate reality of conservatives, cutting taxes on the rich should magically generate full employment; cutting benefits for the poor doesn’t hurt them but makes them more self-reliant and successful; and the best way to supply every American with adequate, inexpensive health care and retirement security is to abolish Social Security and Medicare and give Americans vouchers to shop among competing, for-profit corporations.

Where is the room for bipartisan, cross-ideological compromise? I don’t see it.

Progressives want to preserve and even expand Social Security and Medicare. Conservatives want to destroy them and replace them with vouchers.

Progressives would prefer that social programs be federal, rather than partly or wholly state-based. Conservatives want to send most programs to the statehouses, where they can be whittled down or destroyed.

Progressives want to raise taxes on the rich and fund a more generous safety net. Conservatives want to cut taxes on the rich, cut spending on the poor and shred the safety net.

Even if we had the party system of 1950 or 1960, there would still be no agreement among the left and right. The only difference would be that some of the liberals who support raising taxes on the rich would be liberal Republicans, while some of the conservatives who want to destroy Social Security and Medicare would be Democrats.

So let’s not waste any more time on nostalgia for the supposed golden age of bipartisanship. Politics is not a dinner party. Politics is civil war by bloodless means—ballots rather than bullets. For one side to win, the other side has to lose. And for one side to win, it needs to mobilize enough support to roll over a bitter and determined opposition if necessary.

That’s how most major change has come about throughout American history, and that’s how it is likely to come about in the years ahead. Cope with it.

Shares