There's apparently no better time than Thanksgiving to glory in mistreating another person -- as proven by Elan Gale's much-praised social media malpractice this past holiday weekend.

Gale, a producer of "The Bachelor," documented via Twitter his repeated insults directed at a passenger on his flight who'd behaved in what certainly sounds, in his telling, like a self-centered and aggressive manner. His tweets paint a picture of a woman who behaved abominably in an airport, shouting at airline employees and making a flight delay all about herself and her own need to get home. Given the sheer volume of people who'd very recently been through their own transit disasters to make it home for Thanksgiving, there was very little wonder that the Internet wanted to turn "Diane" into a pinata; viral-content mecca BuzzFeed named the incident "epic" and said it had "won Thanksgiving."

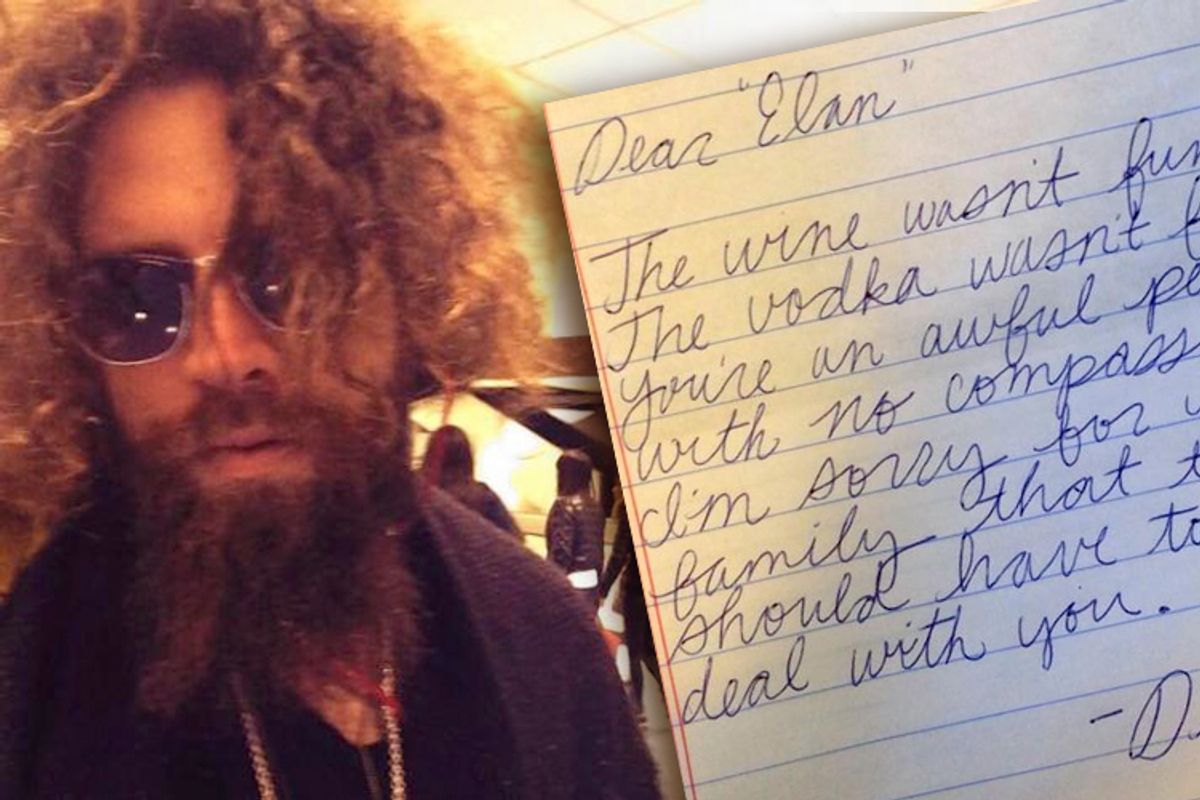

Leaving entirely aside, for now, the ethics of Gale publishing to the open Web for the entire world to see the details of a fellow traveler's low moment, Gale's own behavior is incredibly regrettable. He enlisted the very flight attendants he claims to have been defending against Diane as referees, making them send her alcohol; gave her alcohol herself after they refused; and then told her in repeated passed notes, which he photographed, to "Eat my dick."

What a blow Gale struck for civility! In order to shame a woman who behaved regrettably toward service employees, Gale spent an entire flight plotting how best to torment her, enlisting unwilling service employees in the process (he notes that the same flight attendants he claims he's defending would rather the whole incident weren't happening). The answer he stumbled upon was sexual harassment.

What's saddest of all about the whole thing is that it seems probable that Gale's story of heroism is an invention -- that the best way he could think of to delight his followers is by making up a story in which he violates the privacy of a stranger, repeatedly. Nothing about Gale's story passes the smell test -- for instance, how does he know that "Diane" is "breathing through her teeth" if she is "wearing a medical mask over her idiot face"? As noted elsewhere, how could he have casually dropped a bottle of vodka on her tray-table if she were in the window seat? The mysteries of the case deepen with an anonymous claim, playing off the "medical mask" detail, that Diane had terminal cancer and was soon to die after missing her connecting flight. It seems completely ludicrous on its face -- but so does Gale's story. It's only because Gale's story is a banal hero-vanquishes-villain story with such outsize characters that we want to grab onto it.

Real or no, the "Diane" story is designed to play on the very worst of human nature: the part that knows that one's own behavior is sacrosanct and it's everyone else that's the problem. It gives the frisson of transgression -- Gale's sexual aggression and repeated attempts to unsettle "Diane," long after her comments to airline employees are in the rear-view mirror, are justified at length through Gale's own point-of-view. She deserved it, see, because she had been so cartoonishly awful -- and, putting a button on the whole thing, she hits Gale once the flight lands.

This sort of thing seems likely only to continue as offline life grows more and more intertwined with digital life; would Gale have undertaken this much effort if he didn't have an audience cheering him on, and if he hadn't been able to write a self-aggrandizing blog post about how he's not a hero, the troops are? (Seriously.) "Diane's" misdeed was to berate an airline employee -- rude, yes, but worthy of a sustained campaign of assault after the flight took off? No wonder the apocryphal story about her cancer is so oddly compelling: Gale, himself, makes absolutely no attempt to understand her point of view or to consider there might, possibly, be particular circumstances at play here, even circumstances as particular as "She's having a horrible day."

Dave Eggers' recent novel "The Circle," a dystopian tale about a Google/Facebook/Amazon hybrid taking over life on earth and guaranteeing radical transparency whether its users wanted it or not, got a lot of things about the Internet wrong. What it got, perhaps, more right even than its author might have known is the fact that no action one undertakes can be considered safe from being broadcast to the entire world. That a purported breakdown at an airport ticket counter merited Gale's repeated harassment is curious. That it became the object of fun across the entire Internet says less about Gale than it does about our collective appetite for public shaming, for a straw woman we can flog to remind ourselves that we, of course, know how to behave in society. It's everyone else who doesn't.

There will be many more "Diane" stories; the Web's combination of proscriptive demands on how people must behave and its chilly lack of empathy already embolden its users even before Gale became a viral superstar. Now anyone who wants a follower bump can plot an elaborate revenge on whomever crosses their path. It will go from "epic" to ordinary. Whether "Diane" is real or not is immaterial, really; if a woman on Gale's flight named Diane is alive, she is not the harridan of Gale's tweets. A person named Diane would have her own subjectivity, her own explanations, the right to exist and to be forgiven. "Diane" is just a character in a two-dimensional rage comic.

I get it, of course. Who wouldn't sympathize a little with the desire to, while documenting one's own experience, include the hellish other people one encounters? On the final leg of my own recent trip back to New York, I was stuck on a slow-moving subway car with two teens slowly inflating and deflating balloons and noncommittally twisting and untwisting the balloons into animal shapes. The sound was jarring -- squeaky and blood-curdlingly slow. As I finally prepared to get off at my stop, I quietly snapped a picture of the pair packing what must have been their 30th balloon into a big paper grocery bag. But I stopped short of posting it to Instagram with a snarky caption, though I really wanted to. Maybe they were bringing the balloons to a sick relative. Maybe they were cheering themselves up after getting some bad news. Hey, maybe they were just obnoxious and it was just me having the bad day. But if that were the case, why rope them into it? I'd be able to go home and close the door and be in a private space soon enough.

Shares