Sometime in the night, they heard a faint cry: “Ah!” But they thought nothing of it. Cries were a common occurrence at the Chelsea.

The next morning began as always. Those residents with office jobs hurried off to work, checking their reflections on the way out and sticking their heads in the door of the former ladies’ sitting room to say good morning to Stanley, who always arrived by seven o’clock sharp. The artists tended to sleep late, but a few lumbered across the street for a swim at the Y or went for coffee at the corner diner. At about eleven o’clock, the clerk at the front desk received a call from outside the hotel. A man who did not identify himself told the clerk, “There’s trouble in Room 100.”

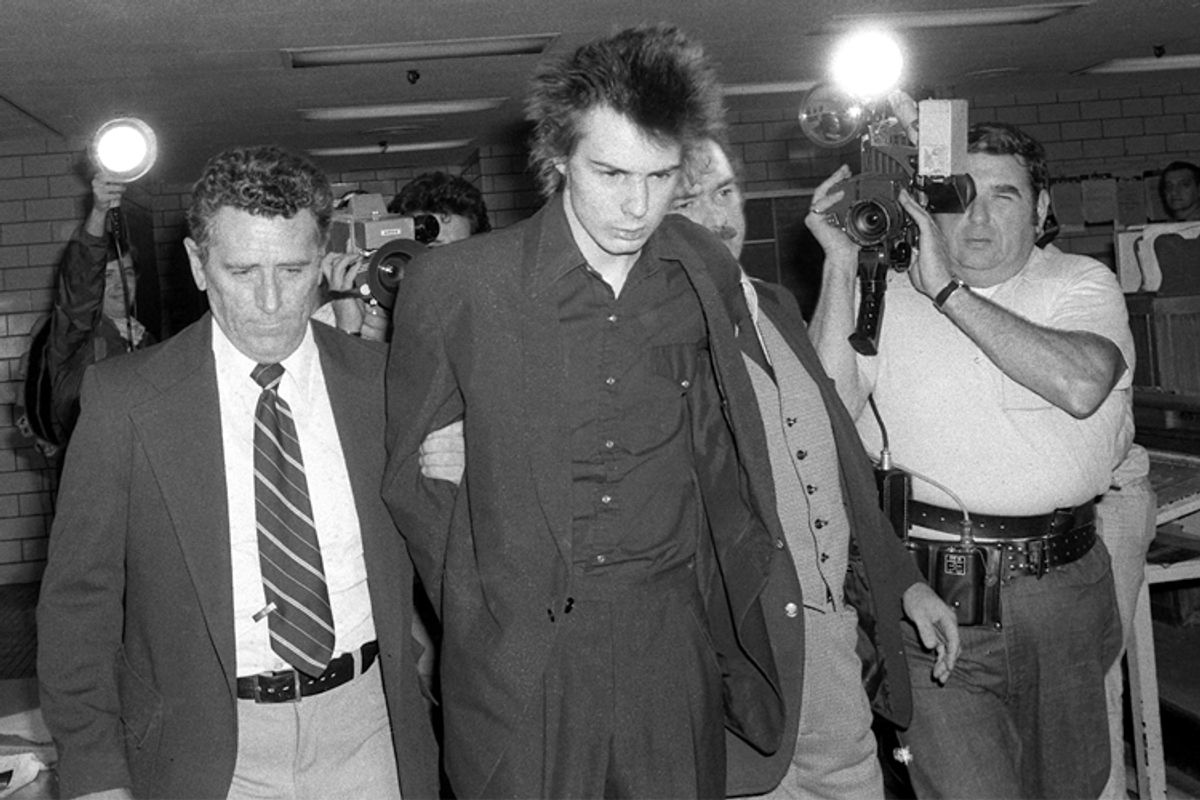

The clerk sent a bellman to check out the situation, but before he returned, another call came in from room 100. “Someone is sick,” a different male voice said. “Need help.” The bellman entered the room and saw, to his horror, Nancy’s blood-smeared body in only a black bra and panties lying face-up on the floor, her head under the sink and a knife wound in her lower abdomen. A trail of blood led from the bathroom to the bloodstained, empty bed. The bellman ran downstairs and told the desk clerk, and he called for an ambulance. The paramedics confirmed that Nancy was dead, and the police who accompanied them soon found a bloodstained hunting knife with the couple’s drugs and drug paraphernalia. They found Sid, too, wandering the hallways, crying and agitated, obviously high. When his next-door neighbor came out of her room to see what was going on, Sid reportedly said, “I killed her . . . I can’t live without her,” but he also seemed to mutter through his tears, “She must have fallen on the knife.”

Once the news broke in the press, the Chelsea Hotel was besieged by reporters, its residents cornered and questioned. One obliging friend of the couple claimed that Sid was known to beat Nancy with his guitar occasionally and had once held a hunting knife to her throat. Inside the hotel, the rumor mill churned. The news spread that Vicious had confessed to the murder, telling the police, “I did it because I’m a dog. A dirty dog,” and that it was he who had phoned the police to report her dead body after he woke up to all the blood. Some people said Sid had bought the knife a few days earlier to protect himself when he went downtown to score drugs; others said Nancy bought it for him as a lark. A debate heated up among those who had been in the room that night as to whether someone who had taken so much Tuinal could have managed to kill anyone. To them, it seemed more likely that Sid had slept through the attack and woken to find Nancy’s body.

As time passed, questions proliferated and doubt grew. Other people’s fingerprints had been found in the room; why were those individuals not questioned? And what had happened to Sid’s royalty money? Might Sid’s dealer, a ferocious-looking Brooklyn native who called himself Rockets Redglare, have killed Nancy and taken the cash? Inevitably, the rumor soon surfaced that Rockets had in fact admitted to the murder to one of Sid and Nancy’s friends. But at the same time, there were questions about the mysterious Michael—now checked out of the hotel—who some said was later seen with a wad of cash secured with Nancy’s purple hair tie. It was hard to settle on a theory, some darkly joked, since just about everyone would have relished killing Nancy. A few even believed she killed herself, part of a suicide pact that Sid had been too stoned to complete.

The only people uninterested in pursuing these questions, it seemed, were the police, who remained convinced that Sid was their murderer even after he retracted his confession, claiming he couldn’t remember anything. Contemptuous of Nancy and satisfied with the story of a punk gone mad, they closed their eyes to the obvious holes in their case. In the meantime, Vicious, released on bail with the fifty-thousand-dollar bond provided by Richard Branson of Virgin Records, descended into a deep depression as the reality of his lover’s death sank in. Dazed and shaking, his eyes glazed over, Sid wanted only to attend Nancy’s funeral. Every day without her was agonizing, he wrote to her mother, and each day was worse than the one before. When Barry Miles spotted him upstairs at Max’s Kansas City in late October, it was obvious that Sid was back on smack. It was a horrible sight, Miles later wrote: “fawning punks, all trying to buy Vicious drinks or hand him drugs while he staggered about, puffy-faced, one eye almost closed, barely able to mumble.” Finally, ten days after the murder, Vicious tried to slash his wrists with a broken light bulb and was carted off to Bellevue screaming, “I want to die!”

Deborah Spungen, Nancy’s mother, arrived in New York from Philadelphia stunned by the news and grieving, though, as the mother of a heroin addict, not really surprised. Still, she was appalled by the detectives’ obvious assumption that a girl like Nancy was just another piece of female refuse in a city that had seen more than its share, that she’d deserved what had happened to her, and that she should now be swept off the streets and forgotten. It was a sentiment echoed in the British tabloid headline “Nancy Was a Witch!,” in the cruel jokes at her expense on "The Tonight Show" and "Saturday Night Live," and in the unending stream of hate calls the Spungens received at home. It was a strange world in which the victim of violence could inspire such loathing, Deborah reflected. Something about an unprotected young woman out in the world, refusing to obey the strictures placed on others, always had and apparently always would provoke society’s rage.

Meanwhile, life went on. In November, the artist Herb Gentry returned from Paris with his new wife, a young American artist named Mary Anne Rose. Oblivious to the tragedy that had just occurred, Rose loved the hotel’s otherworldly quality and fell in love with it for life. That same month, longtime Chelsea Hotel habitué Rene Ricard published an op-ed piece in the New York Times titled “I Class Up a Joint,” laying out the method behind his ability to enjoy a top-drawer existence in the city without ever having worked a day in his life. “If I did [work], it would probably ruin my career,” he explained, “which at the moment is something of a cross between a butterfly and a lap dog.” Claiming he didn’t need much money —that others bought him drinks, fed him, and lavished him with expensive art and jewels — he declared that a job would prevent him from doing his real work, which was “to amuse and delight, giving my rich friends a feeling of largesse, my poor friends a sense of the high life and myself a true sense of accomplishment for having become a fixture and a rarity in this shark-infested metropolis.” Adding that “I should be paid to go out . . . You see, I’m good for business. I class up a joint,” he concluded with the afterthought, “What’ll happen when I’m too old to crack jokes?”

And at the end of November, a convocation sponsored by New York University called the Nova Convention was expanded by John Giorno and William Burroughs’s new assistant James Grauerholz to become a summit meeting of the older avant-garde and the punk movement. Timed to coincide with the long-delayed release of Burroughs and Brion Gysin’s 1965 collaboration "Third Mind," the convention represented a passing of the baton of American culture from the humanism of Ginsberg, Dylan, Abbie Hoffman, and the Lower East Side utopians to the more reptilian and now more representative world of William Burroughs. Performing in the Entermedia Theater were John Cage, Ed Sanders, John Giorno, Philip Glass, Patti Smith, Lenny Kaye, and Frank Zappa, with Laurie Anderson making her public debut, and Brian Eno, Debbie Harry, and Chris Stein attending. Burroughs himself, in business suit and green hat, gave a measured reading of his works from behind an old wooden desk, delivering the bad news about the American dream like “a doctor delivering a diagnosis of a terrible disease.”

In December, as Virgil Thomson distributed the usual gifts and tips to the Chelsea Hotel staff and as his young secretary Victor T. Cardell mailed Stanley a check to cover the costs of refinishing Thomson’s floors, Sid Vicious was released from Bellevue and then arrested again — this time for getting into a fight with Patti Smith’s brother Todd in a downtown club and smashing him in the face with a beer mug. He was dispatched to Rikers Island maximum-security jail, where he spent two months in the prison’s detox wing before being released again on bail on February 1, 1979.

That night, Sid’s new girlfriend of the moment, an aspiring actress named Michelle Robinson, hosted a celebratory dinner at her Bank Street apartment with Sid, his mother, Anne Beverley, and a few other friends. Sid was in a good mood as they listened to Dolls records and joked about the songs that Malcolm McLaren wanted Sid to do for his next album: “I Fought the Law and the Law Won,” and, perplexingly, “YMCA.” After eating spaghetti Bolognese, Vicious asked his mother—herself a hopeless addict—to find him some drugs. When she supplied him with some, he complained they weren’t strong enough, and a friend was sent out with Anne’s money to get more. Unfortunately, this second batch of heroin was “beyond good” — more than 95 percent pure. Sid shot up and collapsed, his tolerance weakened by his period behind bars. Deciding not to call an ambulance, fearing he’d be thrown back in jail, Michelle and Anne managed to revive him. But later that night, alone in the bedroom, Sid shot up again. He was found dead the next morning. He was twenty-one.

Later, Sid’s mother claimed to have found a note in the pocket of her son’s jeans telling her that he wanted to be reunited with “his” Nancy. She asked the Spungen family for permission to bury her son beside their daughter but was instantly and adamantly refused. So the following week, Anne flew to Philadelphia with her son’s ashes and secretly sprinkled them over Nancy’s grave.

Excerpt from "Inside the Dream Palace" by Sherill Tippins published Dec. 3, 2013. Copyright © 2013 by Sherill Tippins. Used by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Co. All rights reserved.

Shares