In the summer of 2012, the writer Jonah Lehrer resigned from The New Yorker. Lehrer, an author of books that translated complicated science into simple-to-understand life lessons, had "self-plagiarized" his own work, re-using his own sentences and quotations without attribution. He had also, more seriously, invented quotations in his book, "Imagine."

The writer Michael Moynihan identified multiple quotes attributed to Bob Dylan in "Imagine" that did not exist in the form Lehrer had used. Some featured portions of actual Dylan quotes, stitched together to form new lines that supported Lehrer's thesis. Some seemed to have been entirely fabricated. Moynihan also listed Lehrer's prior documented instances of lapses of journalistic judgment, including one instance of plagiarizing another New Yorker writer, Malcolm Gladwell.

Reviewing his first book, "Proust Was a Neuroscientist," philosopher Jonathon Keats upbraided Lehrer for a narrative larded with examples that “arbitrarily and often inaccurately” supported his thesis. The writer Edward Champion, who catalogued Lehrer’s recent recyclings on his blog, stated baldly that Lehrer was guilty of “plagiarizing” a paragraph from fellow New Yorker writer Malcolm Gladwell. A New York Times reviewer catalogued the “many elementary errors” in Imagine. And the New Republic’s Isaac Chotiner, in a devastating review of "Imagine," chided Lehrer for “borrowing (heavily)” from economist Edward Glaeser and claimed that “almost everything” in his exegesis of Bob Dylan’s song “Like a Rolling Stone” was “inaccurate, misleading, or simplistic.”

Lehrer's previous employer, Wired.com, asked journalism professor Charles Seife to review Lehrer's work for their website.

Seife reviewed 18 posts and found 14 instances in which Lehrer recycled his own work, five posts that included material directly from press releases, three posts that plagiarized from other writers, four posts with problematic quotations and four that had problematic facts.

Lehrer had plagiarized and fabricated repeatedly, for years. He had violated all of the most important modern rules of journalistic ethics. He misled his readers, stole from other authors and violated the trust of every editor, publisher and media organization that ever published him. An author like that deserves every bit of public scorn he's received, right?

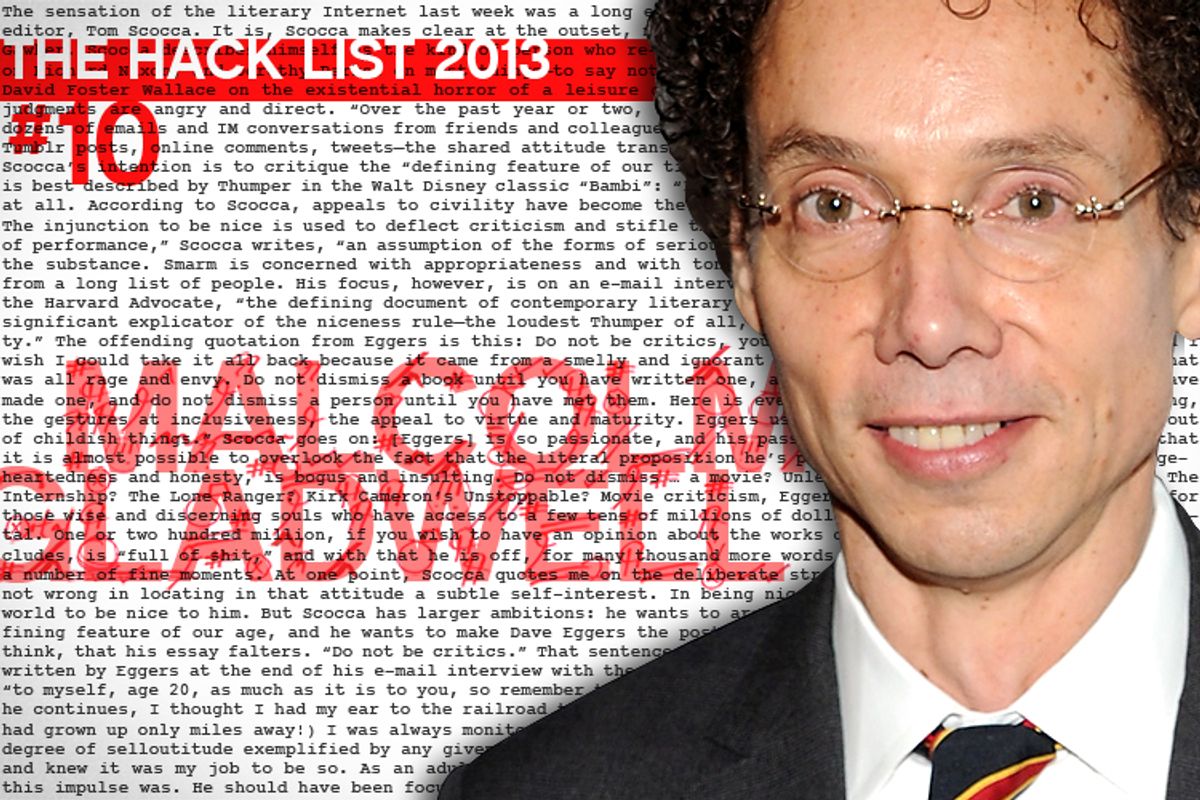

We tend to think, like Seife, that writers shouldn't make things up. But one man, Malcolm Gladwell, says maybe we're just overreacting.

"In the classic sense of the word, it was a hysteria," Gladwell says of the anti-Lehrer uproar. "There was a kind of frenzy about it that was disproportionate to the crime. Jonah screwed up, and he's the first to say he screwed up, but I'm puzzled by how much vitriol was directed at him."

Should a writer mean what he says? We typically think yes. But sometimes writers can say what they mean while also meaning something entirely different. "He says pretty much what he means," Gladwell recently said of another writer, David Eggers. Gladwell also said:

When Eggers says, “Do not dismiss a book until you have written one, and do not dismiss a movie until you have made one,” he does not mean you can’t criticize a book or a movie unless you’ve made one.

A more useful question might be, should an author believe what he writes? Maybe, depending on the subject matter, and the author's intent, a writer can advance arguments the author knows to be dubious in support of shaky, predetermined conclusions, if the author really wants to.

"When you write about sports, you're allowed to engage in mischief," Malcolm Gladwell says. An author, according to Gladwell, can put forth arguments he doesn't necessarily believe, because his books, while labeled "nonfiction," are actually meant not to inform readers of what he believes to be the truth, but rather to "start conversations." What if he's right? What if we took it even further?

Maybe an author can even misinterpret other people's research, and misrepresent scientific findings, if doing so makes a book read better. Maybe saying what you mean, and believing what you say, don't actually mean believing what you say and saying what you mean. Could it be that anyone can justify writing any bullshit at all if they feel like it will start conversations, sell books, and set up high-priced speaking gigs?

--

We all agree that good writers are better than bad writers, and it logically follows that good books are better than bad books. It may seem like an author's best bet is a write a good, well-written book that respects its readers' intelligence. After all, isn't that true of most of the most famous and successful books throughout history? We assume that a good writer is more likely to be successful at writing professionally than a bad one. No parents would wish for their children to be bad writers.

Or would they?

What if, sometimes, being repetitive, sloppy and dishonest -- and being all of those things repeatedly, as more and more people begin to publicly call you out -- is more likely to lead to respect, wealth and success than trying to write honestly and carefully about big and important issues?

What if, sometimes, a bad writer is better than a good writer?

Could writing bad books be better than writing good ones?

--

Malcolm Gladwell was born in 1963, in England. He moved to Canada as a child, and still identifies as a Canadian author. His new book, "David and Goliath," "is a very Canadian sort of book," he says. The theme of his book is that underdogs -- Davids -- win over powerful opponents -- Goliaths -- more often than people think. "David and Goliath," Gladwell says, is "Canadian in its suspicion of bigness and wealth and power."

Gladwell's central story concerns girls' high school basketball. He writes of a team made up of players described as "'little blond girls' from Menlo Park and Redwood City" and "the daughters of computer programmers and people with graduate degrees." Their coach is the founder of a successful Silicon Valley company whose software "powers most of the trading floors on Wall Street." This team plays another team, "this all-black team from East San Jose," according to the coach. We might assume the first girls, with their class and wealth advantages, would be the Goliaths. We might have taken Gladwell at his word when he said his book was suspicious of "wealth and power." We'd be wrong. The rich white girls are the Davids, because they are bad at basketball.

When you start to think this way, new possibilities emerge. Suddenly, nearly any story at all can be used as supporting evidence for your hackneyed premise. Even David isn't a David. Gladwell quotes a ballistics expert who says that the rock could have been propelled from his sling with power "equivalent to a fair-size modern handgun." Goliath was out-armed. Goliath, in fact, had another disadvantage. Gladwell says "many medical experts now believe" that Goliath suffered from a "serious medical condition," and that his abnormal size was the result of a tumor in his pituitary gland. The giant was big, yes, but he was actually a big handicapped person in a fight against a man with a gun. A man with a gun who was a soldier, and the armor-bearer for King Saul. Who represents big and powerful, again? All Davids, it seems, are secretly Goliaths. But Goliaths are also Davids.

--

Christopher Chabris is a psychology professor at Union College in New York. In 2013, he studied Gladwell's newest book in order to write a review for the Wall Street Journal. Here's what Chabris found: In Gladwell's previous book people like attorney David Boies were said to be successful because of their environment (his parents were teachers) and because of hours of work (he debated in college). Now, Boies' success happens for a simpler, more uplifting reason: Because he was dyslexic. Gladwell calls dyslexia a "desirable difficulty."

But there was a problem. There wasn't actually any rigorous evidence for the hypothesis that dyslexia is advantageous. Indeed, there seemed to actually be proof that it's a hindrance to success. The more Chabris read, the more he found bad science used to justify unsupportable claims. One study Gladwell cites had a small sample size, and a follow-up study with a larger one didn't replicate its results, something Gladwell doesn't mention.

So the book is bad, right? Wrong. "In 'David and Goliath' readers will travel with colorful characters who overcame great difficulties and learn fascinating facts about the Battle of Britain, cancer medicine and the struggle for civil rights," Chabris says. "This is an entertaining book."

And Gladwell knew it would be all along. Chabris, like many of us, thought that Gladwell used shoddy research and studies with results that couldn't be reproduced to make grand pronouncements about human nature and society because he didn't know better. But the more Chabris looked into it, the more research he did, the more evidence he found that everything he had originally assumed about Gladwell was wrong.

"I had thought Gladwell was inadvertently misunderstanding the science he was writing about and making sincere mistakes in the service of coming up with ever more "Gladwellian" insights to serve his audience," he says. "But according to his own account, he knows exactly what he is doing, and not only that, he thinks it is the right thing to do."

--

Is Gladwell good or bad for America? The question is trickier than it sounds. His books can be used for bad purposes, like providing facile "leadership quotes" for evangelical leadership gurus. But they can also be used to open people's minds to good ideas.

His previous hit "Outliers" had a similarly pliable central theme -- success entails hard work -- but he used that theme to push messages of social justice and equality. The book contained a convincing and important defense of affirmative action. It was in part a critique of the American notion of individual genius being the primary determinant of success. That idea is central to the conservative movement's entire ethos. Gladwell had nearly become a radical, highlighting class issues and attacking structural racism. As we've seen, he still says that his work is "suspicious" of "wealth." Such a writer would never receive a warm welcome from a reactionary figure like Glenn Beck, right?

Wrong. He would.

Malcolm Gladwell is a good writer. He's written very good profiles for The New Yorker, and even some of the essays that make up his books, especially the earlier ones, are well-written, honest and compelling.

So does it take a good writer to make a successful bad book? Not necessarily -- look at Colton Burpo. But it turns out that the very skills necessary to write compelling profiles and thoughtful explorations of interesting topics can also be used to connect a bunch of anecdotes to some unrelated social sciences work and claim it all proves a conclusion that is basically a truism described as an unexpected insight. And once you can do that, you can do anything -- even get your book hawked to Glenn Beck's credulous audience.

Shares