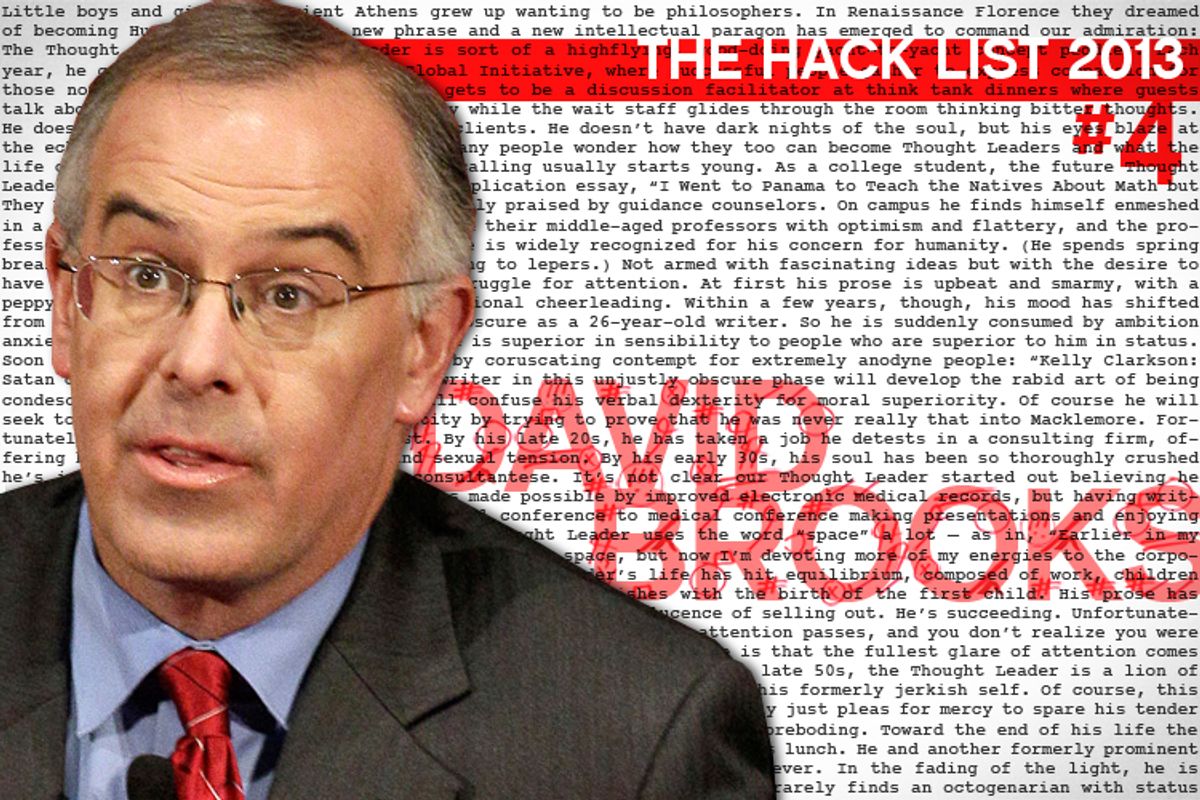

The Columnist

It seems a pleasant life to be a Columnist. He writes a few hundred words once, or at most twice a week. He's paid more to read those words out loud to people at elite colleges and conferences. Naturally, people frequently want to know where a Columnist comes from and how they come to have columns.

The Columnist begins as a Young Conservative Intellectual. It is important for the Young Conservative Intellectual to be a converted radical, so he will have a story of his foolish young radicalism and of his conversion, which he will credit to William F. Buckley and Milton Friedman. He finds meaning in seriousness as a concept. He admires Edmund Burke. The Columnist will be a public intellectual, not a mere pundit. He will be wry, but never funny. Lightly ironic, but never sarcastic. If he mocks, it will always be gently.

The Columnist floats around the Conservative Media for a while, where he is guaranteed work for life so long as he remains ideologically correct, but the columnist has grander dreams. He wants everyone to admire his seriousness, and that will not happen so long as he's writing "The Democrats Are the Truly Stupid Party" and "The Clintons Are Actually to Blame for Enron" at a conservative magazine, where those takes are conventional and expected, instead of an Ideas magazine, where those takes would be fresh and counterintuitive. At the Weekly Standard, "The way George Bush ran his baseball team shows his many impressive leadership qualities" is simple partisan cheerleading. But at the Atlantic? So the Columnist moves to a magazine of Ideas. He writes things like, "Liberals are more materialistic than they claim to be," and "Liberals are less tolerant than they claim to be," and "I have read Reinhold Niebuhr."

Ideas, for those who aren't clear on the concept, are simply attention-grabbing assertions. The Columnist is one of a group of people who create these assertions and sell them to rich people. His first book, "I Confirmed All My Biases By Driving to a Strip Mall," is a big hit among people who like to feel superior while reading gentle mocking of people who like to feel superior. "Some Americans enjoy NASCAR," he writes. "Others prefer arugula and are very proud of themselves for this fact." He treats this observation as a bold Idea. He invents a term, to mock (gently!) a very specific social class, and he freely condescends to a larger one. The Columnist will never deny being one of the arugula ones, of course, he will just position himself as that class' foremost chronicler of its little hypocrisies. His satire was once silly, and Perelman-esque. It is now muted, and practically indiscernible.

In fact, you never know when the Columnist is joking, which allows him to get away with quite a lot. He writes patent falsehoods. A young reporter calls him and points them out. The Columnist asks, don't you get jokes? He says, "Is this how you're going to start your career?" A Columnist does not expect to be fact-checked. He interprets it as a threat, from a would-be future Columnist.

But the Columnist learns that it doesn't matter. The Columnist's work is fantasy, an extensive anthropology of fictitious creations, and other serious people are enchanted. For the serious, a good Idea doesn't need supporting evidence. The Idea is its own justification. The Columnist moves from his magazine of Ideas to his rightful position as official Columnist at the last newspaper.

Of course the Columnist knows he didn't just get this job for his Idea. The Columnist got this job because the last newspaper is liberal, or perceived as liberal, but wants very, very much to also be fair, so one or two of its columnists are conservative. But you have to be a very specific kind of conservative to fit in at the last newspaper, whose most important readers are sensitive, liberal and rich (not coincidentally, just like everyone the Columnist writes about). You have to be a "not-too" conservative, preferably an erudite one who claims his conservatism from, say, Burke. You have to support the Republican Party most of the time but be careful to concede that they've perhaps gone just a bit too far some of the time.

In this unjustly successful phase the Columnist will be one of the most influential people alive. Or at least "influence" will be something else he projects, alongside "seriousness." Our Columnist may not have started intending to become The Columnist. He may have preferred to be a humorist or essayist or maybe even a simple Ideas magazine editor. But no one turns down a column, and now his time is occupied with Sunday show panels, the follow-up books, debates of world-shaping importance (conducted only with other Columnists of his stature), and Ideas Festivals. (The Columnist spends the Bush years being wrong about Iraq.)

By now the Columnist uses the word "modesty" a lot, as in, "A few decades ago, pop singers didn’t compose anthems to their own prowess; now those songs dominate the charts." The Columnist's take is widely praised, and he even wins an award for civility.

Soon, there is even a serious president. The president immediately takes to the Columnist. They bond over their shared habit of mentioning having read Edmund Burke. They are both of them more serious than they are liberal or conservative. The president wants very much to be the sort of president the Columnist likes, and the Columnist wants very much to be the sort of Columnist the president reads. It seems like a perfect relationship.

But the Columnist is secretly already in decline. His party no longer even bothers to put forth the pretense of pretending to take the Columnist seriously. While the Columnist is writing "modesty manifestos" the powerful people he is supposed to have a channel to are all talking Breitbart, not Burke. Of course they had always liked Rand more than Burke anyway, but they had once thought, like the president thought, that they needed to protect their alliance with the Columnist in order to preserve their legitimacy among the serious. It turns out that ignoring the columnist does no damage to the brand. No power is lost when the party spurns the Columnist. The president still talks to the Columnist, but the president no longer acts like his world resembles the Columnist's world.

But a Columnist is secure for life. His influence can wane, and the fun can go out of his work, but he will always be taken care of. He will be asked to teach at a prestigious school. His lack of expertise in any subjects beyond meeting deadlines and the projection of seriousness won't be a problem, of course. Projecting seriousness is a useful tool for future elites. He will call his course something like "Modesty" and while he will prepare himself for snarking from the uncivil mob he will insist that there is nothing inherently ridiculous about assigning his own work in a class on "modesty."

He teaches them seriousness. They teach him Macklemore. He studies his small sample of young people, unrepresentative of anything but their own class backgrounds, and as he always does he extrapolates to the whole. He uses their work for his column, and they dutifully keep up the charade that these specific young people stand in for the entire world of young people.

He gets to know these kids. And he realizes, or decides, that he hates them. They're unjustifiably self-assured. They've got atrocious taste in everything, especially music and politics. They're all unaware beneficiaries of a cushy life of grade inflation. These people are going to succeed him? This miserable bunch, these kids who've mistaken their performance of overachievement for actual achievement of any kind?

He hates them, and he hates, too, the people he imagines them growing into. He imagines them becoming the kinds of people he has always hated, in fact. People who'd helped to erode his status signifiers and people who mock his seriousness. People who write for Web sites. Web sites! And the people writing for Web sites have no deference for the Columnist. He has always dismissed these Web sites, but he now worries they are where new columnists will come from. Younger men, with more marketable sensibilities, adopt his patented method of Idea generation, and generate more buzz than he can now manage. People realize that the Columnist speaks to a constituency of one. Seriousness is still a valuable trait, obviously, and the Columnist will be welcome at Aspen every year for the rest of his days. He will not go hungry. But the Columnist sees this world just beside his own, where his seriousness is disrespected, even scorned. This world is the problem, he decides.

Now the Columnist decides he'll write a column just for his constituency of one.

He writes a column for himself. The column is about those terrible kids. It is about those awful Web site writers. It is about everyone the Columnist knows professionally and socially. Of course, most of all it is about the Columnist. Because the Columnist is an expert in conflating unrelated or irrelevant elements in order to craft an Idea, he will conflate all of the things he hates into one subject, and then he will imagine that subject's decline into irrelevance and existential dissatisfaction. (The column is self-hating, but he is still the Columnist so it is also still self-aggrandizing. The Columnist makes sure to recognize and praise his own modesty and humility, compared to the relentless assuredness of those kids and those Web site writers.)

There are still jokes. There is a joke about Macklemore, a reminder of the column he had those kids write. There are slightly exaggerated observations of the habits and foibles of the Columnist's hyperspecific socioeconomic and regional milieu, of the sort he's always made. Indeed, the central joke is very nearly one he's already made. But the Columnist is no longer lightly ribbing. The Columnist is trying to inflict damage. But no one really understands why, or whom the column is directed at.

Of course, the column that the Columnist wrote for himself, that makes no sense to others, gets buzz. The Web site writers tweet about it on their iPad Airs and the Ideas magazine writers discuss it and drive traffic to it. The Columnist takes no pleasure in the buzz. Death approaches. But until it arrives, no one will ever take away the Columnist's column.

Shares