This month, The New York Times reported that the features unique to e-books had largely fallen away. A format that had originally promised all manner of functionalities was now fairly restrained, similar to an actual book — goodbye, public comments on books, multimedia elements and hyperlinks! Hello, potential embedded author autographs, just like the signed first edition on your shelf.

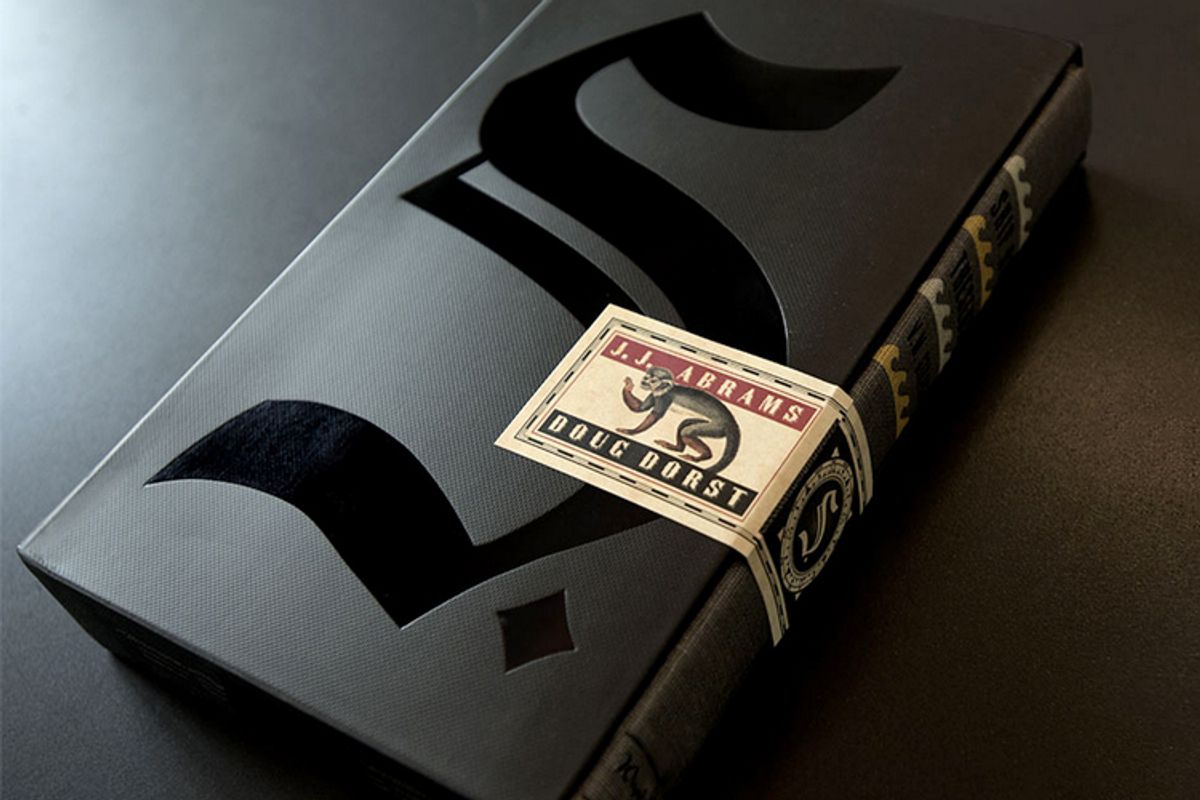

As e-books are stripping down to the bare-bones of what is actually book-like, physical books are growing more sumptuous and fetishistic. Though anecdotally, book covers seem to be steadily improving in aesthetic quality, not every major release, certainly, is as astoundingly detailed as J. J. Abrams and Doug Dorst's "S.," a book full of inserted cards bringing one an immersive multimedia experience, or Chris Ware's "Building Stories," a box containing 14 discrete volumes that can be read in any order.

But those examples from the last two years indicate a way forward for the printed book — as a luxury object. Because the margins (financial margins, that is) for e-books are so much wider than for printed books — they are far, far cheaper to produce than physical books and summarily cost less — there's no compelling reason for anyone with an iDevice or e-reader to spend more money for a paper copy of a book other than aesthetic pleasure.

And, of course, aesthetic pleasure is what books are all about. But the era in which publishers could meaningfully restrict their books from being sold digitally has effectively closed; to refuse to sell a book online, even in spite of how much less money one can make from Amazon than from physical sales in stores, is to cut off a revenue stream and to ensure money is spent on a competing publisher's book. And more and more consumers, accustomed to reading on screens, are using e-readers, and fewer physical outlets even exist to sell books in the first place. If a book isn't immersive and incredibly visual, is there much of a point in seeking out a paper copy?

There exist two sorts of books, though the categorizations will change reader-to-reader. There is the book one simply wants to read, and the book one wants to own — the famous example, cited endlessly in early pieces on e-readers, about the home bookshelves as a sort of trophy case, proving one has read "Crime and Punishment" or, when it first came out in hardcover, "The Art of Fielding." Spending a premium on a paper book so that one can be seen on public transportation reading it or in one's home having read it is a vanity one has every right to pursue. But it is a vanity.

2013 has brought about more opportunities to buy e-books from independent retailers, via vendors like Zola Books or Emily Books. One can now read an e-book without supporting the legitimately evil Amazon apparatus (and feeling the guilt that comes with that). And all of the flashy, distracting elements of e-books have been whittled away due to outright rejection from the public, leaving a product that looks remarkably like a book. The only thing it doesn't have is a physical cover.

The success of "The Goldfinch" recently indicates the degree to which prestige-y titles by famous authors will do fine as physical books — it's precisely the sort of thing one wants as a totem in the home and is aesthetically splendid as an object, to boot. It's being sold at Amazon for $7.50 and its list price is $30, and yet it is a print bestseller. Its companions on the print bestseller list include "S.," the Abrams compendium that simply cannot be conveyed via an e-book, as well as works by reliably best-selling authors like Tom Clancy, John Grisham, James Patterson and Mitch Albom, authors whose books are sold at Wal-Mart. Other authors would be well-advised to embrace the e-book; given how few bells and whistles the e-book bears in its now-successful attempt to evoke the physical book, there'd be little more work involved.

Shares