A piece on Slate argues that the film "Her," which came out at the end of last year and has already been nominated for three Golden Globe Awards, is deeply flawed in its inability to present a three-dimensional woman character. While it's difficult to argue against any call for more adequate female representation on-screen in the era of the Marvel movie, this piece, by Anna Schechtman, misses the point -- "Her" is a film that takes very seriously the issue of men's idealization of women, and uses its actresses brilliantly to tell a story about how men fail to understand vibrant, interesting real women.

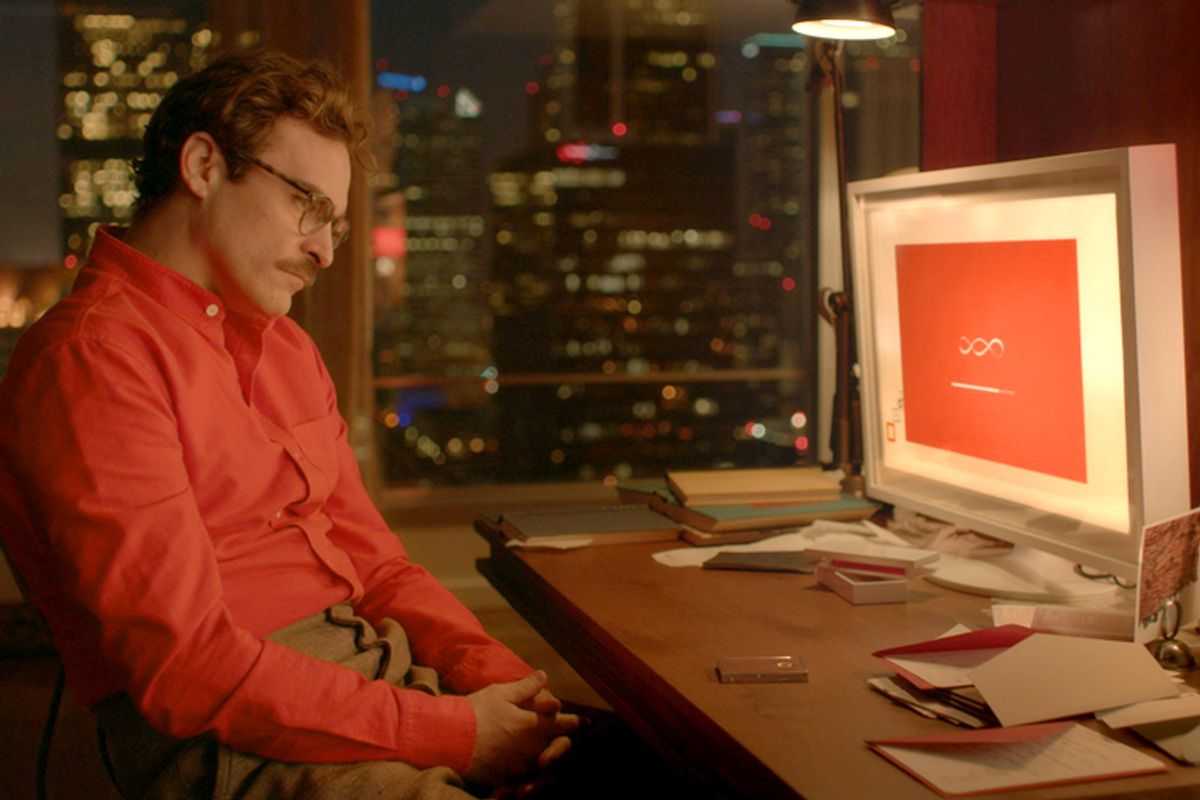

The main cast of "Her" features one man -- Joaquin Phoenix -- and four women; Phoenix plays Theodore Twombly, who, reeling from a divorce from his wife (played by Rooney Mara), falls madly in love with his phone's artificially intelligent operating system, "Samantha." The OS is voiced by Scarlett Johansson, and that it's likely her best performance ever is not a condemnation of her but instead an astounding compliment to what writer/director allows Johansson, as Samantha, to do. The mere fact that Johansson, who recently has been saddled with roles like the Avenger with the least to do or a dour Janet Leigh, was taken seriously enough by Jonze to cast her as a fantasy object with a serious mind ("mind") and a conflicted heart ("heart") speaks well of the film's qualities from the jump.

But it's the mitigating factor of Samantha's unrealness, as a love object, that so irks Schechtman. "Jonze has presented us with the fantasy of womanhood unencumbered by the female form," writes she -- but the appeal of Samantha is never not a bit uncanny or weird for the viewer. The fantasy is explicitly, if not a dark one, one that's dystopic. Theodore Twombly's obsession with her is, though explained away by different characters, not something the movie endorses.

Writing of a scene in which the two have a sort of phone sex as the screen goes black, Schechtman writes: "[O]ur collectively imagined Scarlett-body is not Scarlett Johansson. It is a vague sketch of sex appeal, easier to control—and to fetishize—than any actual woman-seen." Right. But this evocation of female sexuality as easily controlled isn't what the film is telling us is inherently good; calling to mind the control Theodore seeks to have over women doesn't mean Jonze is seeking the same control. (If anything, making Samantha invisible totally forecloses the option of the "male gaze" -- Schechtman's argument would be easier to parse if Samantha looked like Lara Croft on Twombly's screen.)

Time and again we see women lambasting Theodore for living in a fantasy world, and not just with Samantha. A date played by Olivia Wilde tells him she is too old to date men like him, men who aren't serious about finding love; Schechtman frames her arrival as a "buzzkill" because of its effect on Theodore, but as a viewer I found it bracing -- finally, someone is explicitly telling Theodore what his problems are! Matters of what is or is not a wholly rounded character are up to the viewer's opinion, but far from Schechtman's concerns that the movie shrugs off "embodied female sexuality," I found Wilde's unnamed character worthy of a Beatrice Straight-style Oscar for a cameo; she's soulful, witty, dirty and ultimately disillusioned by Theodore. That Theodore has sex with his computer after breaking his human date's heart seemed to me less of an invitation to imagine the computer's sexy invisible form but reinforcing that she has none, and that the women on the film's margins have so much more to offer.

Wilde's acting was another welcome surprise from her, but a director doesn't cast Rooney Mara and Amy Adams to do lightweight work. Mara gets her own great scene, one in which she builds an entire history with Phoenix over a meal as they sign their divorce papers and litigate the end of their relationship. Adams is the soul of the movie, a wistful documentarian whose own relationship falls apart, as she explains in a heartbreaking scene; that she has "no sexual inclinations," per Slate, is not a bug but a feature of her character. She's trained herself to be "good" in the eyes of hyper-controlling men like Theodore or her ex until she reached a breaking point. All of these women are three-dimensional -- it's just that they're purposely marginalized, because we're seeing their world through the eyes of a solipsistic dope who takes tiny steps toward reforming by the film's end.

"Among all the film’s female characters, where is 'she' in 'Her'?," Schechtman writes. There ... are three? The age of consciousness about gender roles in cinema that has given the world Bechdel-test ratings for movies is a net good, but the fact that one doesn't like the way a character views and treats other characters doesn't mean a movie is flawed. It means you're seeing the world the way the director intended -- and even before the cut to black, it's a dark world, indeed.

Shares