On an October evening in 1893, homeopaths from the Hahnemann Medical College marched proudly down the streets of Philadelphia in the city’s annual medical parade. Cheered on by the crowd lining the streets, the students carried canes and waved banners in the royal blue and burnt orange of their school, proudly displaying their motto: “In things certain, unity; in things doubtful, liberty; in all things, charity.” Unity and charity were far from the minds of the medical students at the University of Philadelphia, Jefferson, and Medico-Chirurgical colleges, however. After learning that the Hahnemann students were to lead the parade, the regular students flatly refused to participate, claiming that to do so would insult “their health and dignity.” And so the homeopaths from Hahnemann along with students from the Philadelphia Dental College marched down Broad Street alone to the taunts of their regular peers: “Sugar pill, sugar pill, / Never cured and never will. / Rickety roup, rickety roup, / Hahnemann, Hahnemann, in the soup.” Led by a brass band and a squad of mounted police called in to keep order, the 250 defiant and proud homeopathic students called out their school cheer as they passed: “Rah, rah, rah, Hahnemann, Hahnemann, sis boom ah.” It was a sweet moment for homeopaths, and yet another reminder to regulars that after nearly a century, the fight to vanquish their irregular competitors was far from won.

But American medicine had changed substantially in that century. The discovery of germs, the advent of X-rays, and the growth of sterile surgery among other medical innovations began to shift healing away from individual Americans and the home and into the hands of trained experts working in hospitals. Knowledge about the structure and function of the body had finally reached the point where daily medical practice began to change. These developments could not have come at a better time.

The closing decades of the nineteenth century brought major upheavals to nearly every aspect of life. The horrors of the Civil War had shattered the peaceful vision social reformers had promulgated earlier in the century of humanity’s perfection through right living and self-control. Americans still thought it was important to work toward the common good, but to survive and thrive now seemed to demand risk and self-indulgence rather than personal example and self-sacrifice. Many people, especially the newly wealthy, became philanthropists and donated money to causes as the nation’s now well-developed consumer ethos encouraged people to believe that good works—like good health—could be purchased. Meanwhile, immigration brought millions of new people to the United States just as the nation’s workforce shifted from predominantly rural and farm labor to urban and industrial work. Cities exploded. Advances in transportation and communication networks lessened geographical distances and reduced isolation. Technology also made work more productive and efficient. As a result, business boomed. Economic fortunes were made and lost overnight. At the same time, at least half of all workers barely made enough money to survive.

To a nation in flux and looking for answers, scientific progress appeared to be a cultural cure-all. Science held the promise of order and efficiency at a time when the nation seemed to many Americans unable to cope with the disorder and complexities of modern life. In response, nearly all fields began adopting more systematic methods and making claims of specific knowledge and expertise. Medicine, law, journalism, education, and even child rearing increasingly set boundaries defining the scope of their subject and the prerequisites for practicing.

Regular doctors had tried to set these boundaries and stake their claim on medical practice throughout the nineteenth century but to little effect. Many Americans, aided by the loud shouts of irregulars, had dismissed their argument as more mercenary than scientific, a self-interested effort to dissuade people from seeking the services of competitors—and they likely had a point. But advances in medical science now began to change the healing landscape. No longer just rhetoric, regular medicine had new tools and knowledge at its disposal that offered a tangible hope of healing. Americans did not lose their attachment to self-reliance, but many problems now seemed bigger than any one individual could possibly grasp through common sense alone. In this culture, expertise became a trait of increasing popular value. The unwillingness of some irregulars, namely hydropaths, Thomsonians, and mesmerists, to distinguish between formally trained practitioners and those who came to the field through a calling or hands-on experience now made them appear backward and less well equipped to compete with this new class of professional healers.

These scientific advances and cultural shifts fueled the revival of the medical licenses deemed undemocratic earlier in the century. In the 1880s and 1890s, most state legislatures reinstated licensing requirements at the instigation of regular medicine’s state and local societies. Until late in the century, these medical societies had largely proved ineffective at lobbying for the profession, torn apart by internal struggles over theory, practice, and leadership. These organizations grew stronger and more effective with time, and they succeeded in convincing politicians that medicine demanded a basic competency in science. By the late nineteenth century, the image of the ideal doctor had expanded to include laboratory methods rather than bedside manner and observation alone. These licensing laws did not drive irregulars out of practice, however. Homeopaths and the eclectic heirs to Thomsonism were too well established and the homeopaths far too popular to be suddenly outlawed. Regulars only succeeded in getting the licensing laws they wanted by allowing homeopaths and eclectics—the very groups they had originally organized to oppose—to be licensed as well. By the 1920s, many states had passed licensing statutes that covered newer irregular systems too, though it would be many decades until osteopathy and chiropractic achieved legal protection in every state.

Buoyed by the return of medical licensure, the American Medical Association took a far more active political role in the early twentieth century. While still concerned with berating and exposing irregular quackery, the organization also seized on widespread concerns about the dangers of urban life to campaign for sanitation laws, public hospitals, and the creation of a national health bureau to implement and coordinate public health programs. They supported diagnostic tests for cholera and vaccination for diphtheria and required reporting of tuberculosis and other infectious diseases to city and state officials. Associating themselves with these concerns helped to forge an image of regular medicine as a proponent of social welfare and community health at a time when public health had itself because a distinct field of medicine out of concern over urban life. Improving public health could only improve the status of regular medicine in the eyes of patients and the government. The AMA fought to exclude irregulars from this new arena of health care by lobbying to prevent them from serving on medical councils and city boards of health and in public hospitals, efforts in which they mostly succeeded. Irregulars protested what they saw as political moves by regulars to monopolize public health and to destroy competition on the national level. Regular medicine’s enthusiastic embrace of sanitation and hygiene was an especially paradoxical outcome for the hydropaths who had pioneered the principles and practices that underlay these public health campaigns.

Regulars also pushed for educational reforms in the nation’s medical schools. At the recommendation of the AMA, the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching sent high school principal Abraham Flexner to evaluate the ability of regular, eclectic, homeopathic, and osteopathic schools in the United States and Canada to produce doctors trained in regular methods. The famous Flexner report of 1910 revealed the sorry state of medical education. Flexner wrote complete analyses of each school. Of the 155 he visited, he recommended that 120 schools should close. Flexner declared the majority of the regular schools “utterly wretched” and “hopeless affairs” and discounted all irregular institutions as “worthless” and “fatally defective.” He found most schools to be proprietary or commercial medical enterprises with minimal academic standards and little or no connection to the hospitals and laboratories that had increasingly become central to the provision of care. In the competitive rush to attract students, many proprietary medical schools, regular and irregular alike, had shortened terms and eliminated staff (or never hired them in the first place) to maximize profits. Although he had few kind words for regular schools, Flexner saved his particular scorn for irregulars. He warned that opening the profession to anyone who wanted to be a doctor endangered the well-being of society and the nobility of a profession dedicated to service.

The Flexner report quickly achieved mythic status for catalyzing the reform of medical education in the United States, but its methods and conclusions, particularly concerning irregulars, do raise questions. Who could be surprised that irregular schools did not turn out regular physicians? That was not the goal of an irregular medical education. Flexner was also accompanied in his survey by regular doctor Nathan P. Cowell, secretary of the Council on Medical Education of the AMA. Hardly a disinterested party with regard to the outcome of the report, Cowell’s council had in fact set the standards Flexner used to assess the schools, and the AMA had never seen irregular schools as anything but counterfeit. That’s not to say that the nation’s medical education did not need improvement—better-trained doctors would result in better medicine—but the political and economic motivations of those behind the Flexner report provided just as much if not more motivation than any idealistic appeals to improve the quality of medical education.

In the wake of the report, nearly half of the nation’s regular medical schools closed. Many schools that admitted women and African Americans, which tended to be weaker and financially unstable to begin with, closed. Those that survived drastically upgraded standards. Flexner had recommended that all medical schools require entrants to have a college degree and encouraged the adoption of a four-year medical curriculum. As encouragement, he persuaded the Rockefeller Foundation to make grants to those schools he hand-selected as worthy of investment. He chose mostly long-established institutions in the East as well as a handful in the South, Midwest, and West. Rockefeller’s contributions stimulated other donations to support medical education. Many irregular schools also improved their curriculum to match the new standards of regular medicine. While some of these irregular schools carried on, many failed, done in by the high costs of upgrading facilities and hiring high-quality staff. The net effect of the Flexner report was to widen rather than narrow the gap between the best and worst schools.

Not every irregular kowtowed to Flexner’s findings. Chiropractors, in particular, protested his recommendations. They argued that the adoption of Flexner’s educational standards would exclude worthy but financially strapped students from becoming doctors. In the past, a lower-class person could become a doctor through hard work and desire. Under Flexner’s plan, he or she would stand little chance because of the costs of obtaining both a college and medical education.

The chiropractors did have a point. Requiring college degrees for medical school admittance excluded a majority of the population: more than 90 percent of Americans did not have bachelor’s degrees even by 1920. Longer and more costly training made medicine more exclusive and less accessible to minorities, women, immigrants, and working-class Americans. Flexner, for his part, likely thought curbing enrollment a laudable goal of educational reform. He warned that awarding too many medical degrees only suppressed salaries and limited the field’s ability to attract the best students. “It is evident that in a society constituted as our modern states,” wrote Flexner, “the interests of the social order will be served best when the number of men entering a given profession reaches and does not exceed a certain ratio.” Raising standards was an effective means of reducing the number of doctors and increasing the social and economic status of the profession. Unlike many of his peers who believed female doctors would also lower medicine’s status, Flexner actually supported coeducation in medical schools, though he rather myopically editorialized, “[N]ow that women are freely admitted to the medical profession, it is clear that they show a decreasing inclination to enter it.”

The path was hardly free and clear for women. Flexner speculated that fewer women entered medicine either due to a drop in demand for women doctors or less interest among women in becoming doctors. Neither was true. The closure of irregular medical schools and close alignment of others with regular medicine had a particularly detrimental effect on the women who achieved professional medical careers in irregular health care. Middle- and upper-class women had made great strides in the late nineteenth century, comprising 10 percent or more of enrollment at regular medical schools. While many attended female-only medical colleges, women still made up nearly 20 percent of the medical profession in eastern cities like Boston, New York, and Baltimore by 1900. But lacking adequate financial support, especially as medicine became more technologically sophisticated, many of these schools closed in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The result was a sharp decline in female medical students even before Flexner issued his report. Coeducation remained an option, and one that many women themselves wanted, but regulars did not make it easy. Oliver Wendell Holmes acknowledged that women brought something unique to healing, but he stopped short of endorsing women’s professional participation in his field. “I have often wished that disease could be hunted by its professional antagonists in couples—a doctor and a doctor’s quick witted wife,” wrote Holmes. “For I am quite sure there is a natural clairvoyance in a woman which would make her . . . much the superior of a man in some particulars of diagnosis.” Holmes was sure that “many a suicide would have been prevented if the doctor’s wife had visited the day before it happened. She would have seen in the merchant’s face his impending bankruptcy while her stupid husband was prescribing for his dyspepsia and endorsing his note.”

Regular medical schools routinely failed to provide opportunities to women and habitually limited the number of women they would even accept at a token 5 percent until the mid-twentieth century. School administrators justified excluding qualified women by claiming that most would give up their medical practices after marriages, so they were not worth the investment. Even those men who seemed to support women’s participation in the field betrayed certain biases about women. John Dodson, dean of Rush Medical College in Chicago, praised his school’s female students as “a credit to themselves and to us” but concluded that “no matter how superior these students may have been in their college work,” they “cannot but do otherwise than rejoice when matrimony claims them.” A medical education also cost more as schools passed the expense of new equipment and faculty, expanded facilities, and lengthened training time on to students. Many women who had once financed their medical education by working could no longer afford to do so. At the same time, the propriety of men and women studying the human body together in the same room remained a potent and divisive issue.

It seems not far-fetched to say that women’s involvement in irregular health systems from the very beginning provided all the evidence some regular doctors needed to dismiss it. In 1893, Harvard professor Edward H. Clarke warned that excessive intellectual activity diverted a woman’s limited supply of energy from reproduction to the brain, which threatened not only her health but also that of her family and society. It was true that women could pursue the same educational course as men, Clarke declared, but “it is not true that she can do all this, and retain uninjured health and a future secure from neuralgia, uterine disease, hysteria, and other derangements of the nervous system.” Worse, women engaging in men’s work “unsexed” themselves by taking on male roles, and thus supposedly male traits, rendering them unable to have the children that would sustain civilization.

Medical texts touting the terror of women’s equality and autonomy flourished. Many used scientific and medical language to rationalize women’s exclusion from active public and professional roles. Dr. Alfred Stille, in his presidential address to the American Medical Association in 1871, declared, “Certain women seek to rival men in manly sports, and the strong-minded ape them in all things, even in dress. In doing so, they may command a sort of admiration such as all monstrous productions inspire, especially when they tend towards a higher type than their own.” The reverse was also true, though: those men who performed the same tasks as women lost their masculinity. Dr. Stille warned that “a man with feminine traits of character or with the frame and carriage of a female is despised by both the sex he ostensibly belongs to and that of which it is at once a caricature and a libel.” Working with women or spending too much time in the feminizing clutches of mothers, teachers, and wives sapped a man’s masculinity. These societal assumptions could not help but influence perceptions about irregular health systems, particularly those like hydropathy and homeopathy where women took active leadership roles. With women in charge, irregular health was marked as both dangerous and ridiculous.

Even with these barriers, women did not stop practicing medicine. Osteopaths, chiropractors, and Christian Scientists welcomed women into their professional fold. Other women, particularly homeopaths, organized locally and focused on lay practice through the first half of the twentieth century. Still more entered regular medicine in nursing and social work, careers that closely aligned with cultural assumptions about women’s more caring nature, and as such were structurally subordinated to the mostly male doctors.

The AMA’s gains and control of public health along with the quickening pace of medical advances in the first decades of the twentieth century significantly challenged the strength of irregular medicine. The introduction of the first antimicrobial drugs, known as sulfonamides, in the 1930s presented a significant breakthrough in the fight against infectious disease and paved the way for the antibiotic revolution in medicine. The mass production of penicillin in the 1940s nearly eliminated diseases that had plagued humans for centuries, including syphilis, meningitis, and rheumatic fever. Streptomycin in 1945 dramatically reduced cases of tuberculosis and plague. Even better, these drugs were some of the first non-homeopathic remedies to cause few side effects. Americans clamored for these “wonder drugs,” and doctors dispensed them with what historian James Whorton has called “antibiotic abandon.”

The 1950s and 1960s saw the introduction of even more antibiotics, vaccines for polio and measles, the CAT scan, heart and kidney transplants, and coronary bypass surgery. In 1953, James Watson and Francis Crick announced their findings on the structure of DNA. Controlled clinical trials became the gold standard for assessing the safety and efficacy of new therapies. As deaths from infectious disease dropped, regular medicine rose in public status, trust, and esteem.

Medicine also grew more bureaucratic, structured, and regulated throughout the twentieth century. That trend was already apparent to Mark Twain in 1900. “The doctor’s insane system has not only been permitted to continue its follies for ages, but has been protected by the State and made a close monopoly,” he wrote, calling it “an infamous thing, a crime against a free-man’s proper right to choose his own assassin or his own method of defending his body against disease and death.” Twain had long supported free choice in medicine, even as he sometimes ridiculed the options, but that freedom became increasingly constrained as the century wore on. More medical care happened in hospitals, where regular doctors controlled access and tended to exclude irregulars from practicing in their wards. Specialty boards licensed and certified practitioners, and the federal government took a more active role in subsidizing medical research and approving drugs and therapies for public use. For regular doctors, these institutional and political structures eliminated many of the economic and political uncertainties that had plagued the profession in the nineteenth century. Competition with irregulars no longer provoked the same anxiety and financial peril, even if it seemingly did little to blunt professional handwringing over irregular practice.

These structures of bureaucratic control, according to historian Charles E. Rosenberg, tightened the boundaries between regular and irregular doctors. Regular doctors tended to view the growing inflexibility of medicine as an affirmation of their system’s scientific validity and stature. To regulars, the fight over public perception and for medical authority appeared finally won.

Yet despite all of these advances in medical science, it was also becoming apparent that many of the wonder drugs were less than wonderful. Patients eager for the latest miracle drug they had learned about in newspapers and on television came asking for remedies and treatments by name. Under pressure both to cure disease and to satisfy their patients, some doctors overprescribed. Many people became addicted to the amphetamines and tranquilizers they took for anxiety, depression, insomnia, and other chronic ailments—a problem that persists to this day. The dangers became even more apparent during the thalidomide tragedy of the 1960s. The drug, marketed as a sedative, one of the most popular and widely used classes of drugs in the United States, was found to produce serious birth defects. Suddenly, the drugs that had seemed so promising now seemed to many Americans to be more dangerous than good.

More than just the physical threat of these drugs, some also decried the breakdown of the doctor-patient relationship. Few could dispute that scientific and technical advances in medicine had improved the health of the nation and decreased the dangers of infectious diseases, but at what cost to personal health and individualized attention? Doctors gave drugs for everything, critics claimed, without listening to the particular ailments of their patients. The exam and patient history that had long defined the medical experience now took a backseat to the medicine bottle, surgical procedures, and test results. Regulars worked under growing structural and financial constraints that eroded the amount of time they could spend with patients, leading to a strained discussion of the specific problem rather than a longer conversation that took account of the context of the problem. As a result, some patients complained that their doctors paid them little attention and were unwilling to communicate with them about their health in a clear and understandable way.

Regular medicine’s increasing fragmentation into specialties also made medical care more expensive, even out of reach for many Americans. Doctors, who had already been concentrated in urban areas, accelerated their movement to city and university hospitals, leaving medical shortages in rural areas. That these specialists also made more money only encouraged this trend. Unlike before, though, the nation’s hills and back roads no longer crawled with the herb doctors, midwives, itinerant folk healers, and bonesetters who had provided care where no other existed. Critics derided the medical profession as self-serving, elitist, and insensitive to the needs of patients for these holes in the system: a condemnation as familiar in 1960 as 1860.

Growing American disillusionment with regular medical practice and the high cost of care in the 1960s and 1970s led some to explore irregular medicine. Just as in the nineteenth century, broader cultural forces were at work. The Cold War, Vietnam, and atomic energy, among other social and political forces, made life feel uncertain and beyond individual control. In response, a counterculture emerged that rebelled against the authority of the government, science, and experts. Its members, mostly white and middle class like many of the nineteenth- century reformers, focused intently on tolerance, natural living, and individual rights. They embraced a simpler, more spiritual orientation to life that integrated the mind and body into well-being. These cultural trends burnished the appeal of irregular medicine. Americans rediscovered homeopathy and botanical remedies as well as a host of other therapies like naturopathy and the hydropathic Kneipp Cure. Health foods, exercise routines, and vitamins became topics of broad popular interest. To a new generation, irregular health-care approaches represented freedom, self-reliance, personal empowerment, and affordable care, the familiar chords that had stoked American health reform in the nineteenth century.

Of course, most of these new alternatives were not new at all. Nor had Americans ever stopped self-dosing and using irregular medicine. It was certainly true that many popular nineteenth-century health systems were not as strong or as visible in the mid-twentieth century as they had once been. Many Americans did not even realize the significant historic challenge irregulars like homeopaths had once posed to regular medicine when they began to emerge again in the 1960s and 1970s. But these healers had never disappeared. The number of homeopaths, phrenologists, mesmerists, and botanic healers sharply declined in the early twentieth century, but osteopaths, chiropractors, and many other kinds of healers made up for the retreat of older systems. In the 1920s, the Illinois Medical Society found that among six thousand Chicago residents, 87 percent reported using what regular medicine had taken to calling “cult medicine.” A similar national survey carried out by the federal government between 1929 and 1931 found that irregular practitioners comprised 10 percent of all healthcare visits. And in 1965, homeopath Wyeth Post Baker released confidential reports from the Senate Finance Committee revealing that an estimated twelve million people used homeopathic remedies without the advice or consent of their doctors. The tenacity of irregular health care’s appeal to the general public alarmed regulars: many had assumed irregular medicine’s demise decades earlier and had consigned its remaining users to a small fringe on the margins of society. These surveys told a different story. While it was mostly true that regular medicine had seized political and institutional authority in the twentieth century, at the level of daily practice and individual therapeutic choice, the ground remained highly contested.

The renewed interest in and popularity of irregular medicine in the 1960s led to the adoption of the words “complementary” and “alternative” to describe the systems that regulars had labeled “irregular,” “unorthodox,” “cultish,” and “quackery” for more than a century. These terms better reflected how many Americans saw and used irregular therapies for centuries—as an accompaniment or substitute for regular medicine. Calling something “regular” or “irregular” implied a common understanding of what constituted legitimate medical practice that many Americans (and many of their doctors) may not have shared even as they used these names to describe their healers. It’s doubtful that nineteenth-century Americans saw their healers as “irregular” or as “quacks” in the negative way that we have come to understand the words. Based on how many people used irregular treatments and with what frequency they sought an irregular’s help, irregular health was a regular part of daily life.

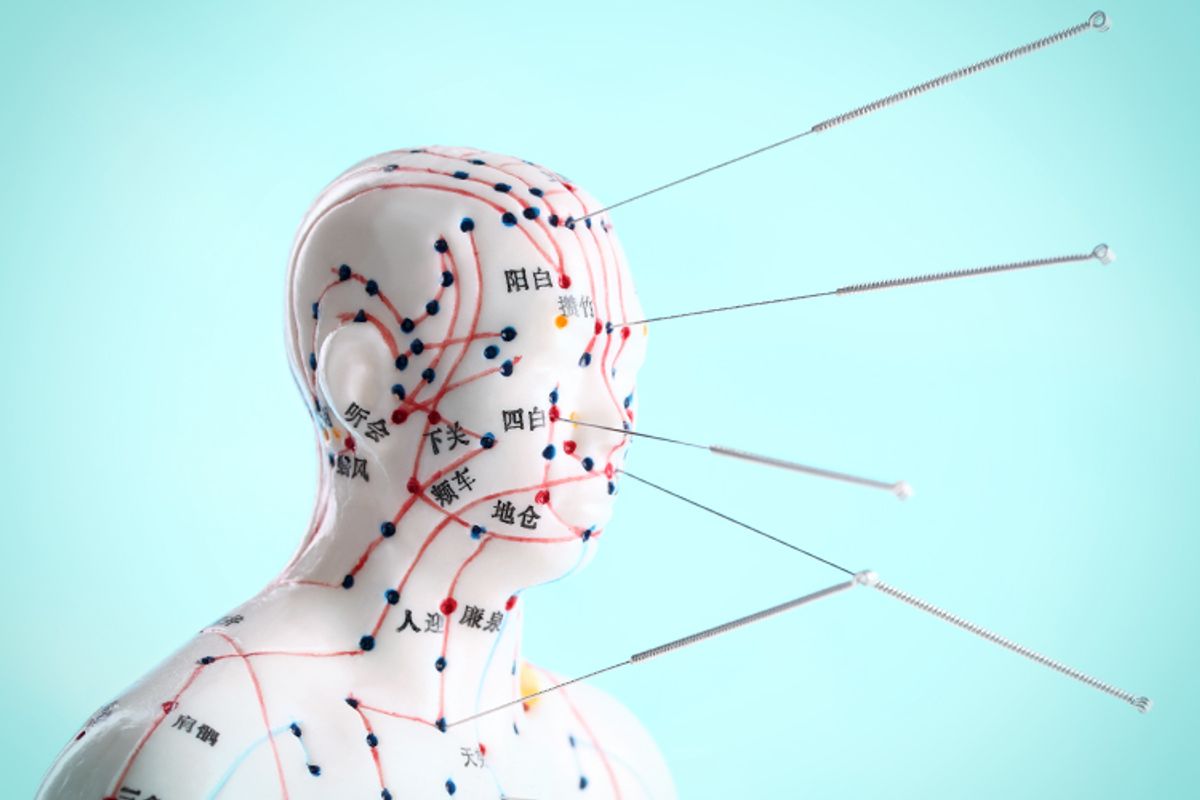

Irregular medicine also became known as “holistic” in the 1980s. Broadly speaking, holistic meant anything alternative and “natural” that took into account patients’ mental status and their social and physical situation. Unique as the concept seemed, though, holistic principles could be found in medical practices as ancient as Ayurveda in India and Qigong in China as well as in hydropathy, mesmerism, Thomsonism, homeopathy, osteopathy, and even the humoral theory that underlay regular medicine. Until the mid-nineteenth century, prevailing therapeutics and understandings of disease assumed multiple causes. Environmental, emotional, moral, and social factors all determined sickness and its cure. Advances in physiology, chemistry, bacteriology, and pharmacology as well as medical technology in the late nineteenth century began to change regular medicine’s perceptions of disease and what counted as medicine. The diagnostic precision and objectivity of scientific medicine promised one path to the truth, not multiple paths. Disease became less amorphous, recast as a specific thing with characteristic patterns and mechanisms best understood through laboratory analysis rather than social and environmental factors. Holistic treatments designed to treat the whole person rather than to attack any specific disease largely fell by the wayside in regular medicine while irregulars tried, with varying success, to incorporate the science without sacrificing their holistic approach.

But in the 1970s, perhaps influenced by the resurgence of irregular health, some regular doctors began to show interest in holistic medicine. In 1979 a group of regulars organized the American HolisticMedical Association and announced themselves “dedicated to the concept of medicine of the whole person,” which may “demand combination of both orthodox and non-damaging unorthodox approaches.” That some regulars accepted the idea of holistic medicine was not news by the late 1970s, nor had it been in the past, as many regulars had never taken the hard line against irregulars or their therapies that the AMA demanded. But the establishment of a professional organization of regulars dedicated to the integration of body, mind, and spirit certainly was. Even more arresting, these regular doctors envisioned a possible collaborative future for irregular and regular health. The organization’s Journal of Holistic Medicine soon included a list of acceptable topics for publication in its pages, a list that included homeopathy. Rarely, if ever, had regulars discussed homeopathy as anything other than a fraud. Now it could be featured and studied in a regular medical journal? Not every regular was sold on the idea of holistic medicine, though, and many of its advocates met with the skepticism and sometimes harsh rebuke of colleagues.

Public enthusiasm for holistic and alternative remedies only continued to intensify, though. Drugstores and health food stores began to carry nonprescription homeopathic remedies as well as other botanical remedies and mesmeric-like medical magnets in the 1980s. By the late 1990s, consumers could actually purchase homeopathic kits just as they had been able to in the past, and sales of homeopathic remedies grew 20 percent annually. Alongside these well-established remedies, though, came an explosion of products labeled “holistic” and “natural” that sought to cash in on the potential marketing bonanza, just as medical entrepreneurs had in the past. Dr. Arnold Rellman, editor of the New England Journal of Medicine, complained that the valuable message of the holistic movement was “ill served by those who seek quick solutions to the ills of mankind through the abandonment of science and rationality in favor of mystical cults.”

Then in the 1980s, concerns about the nation’s rising health-care costs led to an even more remarkable endorsement of alternative medicine—one nearly unthinkable only a few decades earlier. In 1991, the US Senate Appropriations Committee instructed the National Institutes of Health to develop a research program in alternative medicine. Championed by Senators Tom Harkin of Iowa and Orrin Hatch of Utah, the Office of Alternative Medicine (now known as the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine) was hailed by some as a victory for irregular medicine while others denounced it as tax dollars wasted on snake oil. Skepticism about government funding for alternative medicine has not stopped major academic medical centers from establishing integrative clinics combining irregular and regular health—Harvard, Yale, Duke, and the Mayo Clinic are among more than forty across the United States. Irregular medicine is more accepted in Europe, where a relatively large number of regular doctors either recognize or practice some form of irregular therapeutics. The emergence of these centers in the United States seems to indicate the willingness of regular medicine to consider or at least tolerate the merits of their competitors, an almost unimaginable idea less than a century ago. While a cynic could attribute integrative clinics to a heedless grab for precious research dollars, it’s not hard to find true believers on the ground. Even outside integrative medicine clinics, many doctors now recommend meditation, discuss exercise habits, and emphasize good nutrition to patients. Among the nation’s most widely read and popular doctors today are Deepak Chopra and Andrew Weil, regular doctors who champion integrative health. The Harvard-educated Weil emphasizes diet, botanicals, and mind-body techniques in his practice. Chopra uses the Indian Ayurvedic system and focuses on the spiritual nearly as much as the physical in his teaching. Millions of Americans read their books, watch them on television, visit their websites, and pay close attention to what they teach. Their followers are not ignorant or uneducated, the reflexive explanation some regulars have put forth to explain the popularity of irregular medicine. Several studies have shown that those Americans with more education, including 50 percent of those with graduate degrees, and a higher economic status are more likely to use alternative medicine than those less educated and less affluent. They share much the same demographic profile as the well-educated, middle- and upper-class white Americans who found irregular medicine so attractive in the nineteenth century. Many of these Americans turned to irregular medicine for help and found it effective. That personal experience goes a long way toward explaining the long history and popularity of irregular medicine in the United States, even if popular lore and historical thinking tends to tell a different story.

Irregular medicine often gets blamed for the problems that were, in many ways, the problems of the larger nineteenth-century American culture in which they arose, practiced, and prospered. It’s far easier to make fun or to hold up irregular health systems as a bizarre specimen of the past than to try to understand what they meant and the very real problems they sought to address and continue to address to this day.

Irregular health resonated with concerns about the moral implications of the inventions and technologies revolutionizing American society in the nineteenth century. The democratic spirit of the century coupled with the emerging capitalist marketplace fostered a climate conducive to the proliferation of reform movements seeking to change all aspects of life. Social movements tend to arise during times of unrest and change, as people become more open to new ideas because of problems they perceive with the status quo. Irregular healers tapped into cultural yearnings for simplicity and a way of life that emphasized hard work, self-improvement, and common sense. They advocated for direct competition and empowered patients to become arbiters of a healer’s merit and efficacy.

During their heyday, irregular healers amassed an impressive record of testimonial success and drew millions of followers. They had a pervasive influence on American cultural trends in areas ranging from egalitarianism and women’s rights to philosophy, religion, literature, linguistics, and science. Stories about phrenological readings, homeopathic remedies, and trips to the water cure filled newspapers and magazines. Irregular therapies became part of storylines in novels and their jargon was used in everyday conversation. The very existence of irregular health, even if most regulars saw it as a profound negative, fostered an atmosphere ripe for contemplating new research and theories both within and outside medicine.

Regular medicine in the nineteenth century demonstrated an unwillingness to innovate and take risks. Irregulars, on the other hand, wanted something better and proposed new solutions to old medical problems. Irregulars suggested novel and creative theories about what caused disease and constituted healthy living at a time when medical advancement appeared stalled.

Excerpted from “Marketplace of the Marvelous: The Strange Origins of Modern Medicine” by Erika Janik. Copyright © 2014 by Erika Janik. Reprinted by arrangement with Beacon Press. All rights reserved.

Shares