There is a certain kind of writer who seems to feel that unless he is breaking apart everything that came before him, composing something that in his own view is astonishingly new, he is not writing great literature. Though he is sincere in his wish to be a great writer (and in that sense might seem almost naive), his preferred mode of public address is sarcasm or heavy irony, both of which are meant to suggest his sophistication, his superiority to banal questions about reality, authenticity, and truth. He has no interest in accurately representing human behavior, partly because he has no interest in accuracy and partly because he has very little interest in other people; what concerns him most is the working of his own mind. He hates with a passion the realist novelists and formalist poets who came just before him, and he is convinced that only he, among all the writers who ever lived, is producing work that will matter to the future. In this respect, he evidently imagines a future filled with people who are nothing like him—people who will be content to rest with the innovations he has produced and will not feel obliged to stomp on their forebears.

Writers like this have given novelty a bad name. They have led those who are wedded to old-fashioned notions of plot and character to conclude that innovations in style or structure are antagonistic to these older values, as if we could only have one of the two aspects—let us call them startling originality and enduring sympathetic gratification—so we have to choose between them. This obsessive clinging to the cherished ways of the past is almost as bad as its opposite. It is equally humorless, equally self-enclosed, and equally unlikely to lead to the production and enjoyment of great literature. I have no prescriptions for producing great works, but I have enjoyed a vast number of them, and from this outsider’s perspective I can pretty confidently say that what is entailed has an element of openness to it. Rigid rules of any kind will be of no use here. Nor will the overweening desire to achieve newness, on the one hand, or protect tradition, on the other, because both of those positions imply a goal that is separate from, and often detrimental to, the more intrinsic purpose of simply telling the truth as one sees it. I say “simply,” but it is not at all a simple matter. Literature that tells lies is not worth the paper it is written on, but a lie is not the same as a fantasy, an invention, an allegory, a myth, a dream. Fiction, drama, poetry, and even essays can be made up and also truthful.

Usefully for my purposes, one of the works of literature which most strongly expresses this complicated view is also one of the most innovative in form. I am referring to Miguel de Cervantes’s "Don Quixote"—perhaps the most stylistically ambitious novel ever undertaken, in no small part because it was one of the first. What does it mean for an author to get inside his characters’ minds and relay their thoughts, rather than simply displaying their actions on a theatrical stage? What is a “narrator,” and how does he connect with the author of a work? How do the realities of fictional characters’ lives compare to the realities of readers’ lives, and where, if anywhere, do the two planes intersect? Does the book exist in its own time or in the time when you are reading it, and does that mean it exists in a different way for each new reader? Can the reader himself inhabit more than one era, time-traveling through books? Can the past, in this sense, be made to live again, and if so, can the nonexistent, purely fictional past also be brought to life? Are dead authors different from living ones, from a reader’s point of view? How do poetry, drama, history, and fiction overlap? What is novel about the novel?

Cervantes was possibly the first person to ask most of these questions, and probably the first person to answer them— not flatly or pedantically, but with hints, suggestions, jokes, and intimations, through novelistic strategies that honored plot and character even as they worried about the existence of such things. There is no ancestor-stomping in "Don Quixote," in part because the book had no immediate ancestors: it was sui generis, emerging from Cervantes’s brow like Athena from Zeus’s, whole and perfect.

The tone is sardonic but also genial, at once sharp, critical, empathetic, and companionable. The hero—a devoted reader, just like us—is the most lovable madman imaginable. (Dostoyevsky’s Prince Myshkin perhaps runs a close second, as he was intended to do, for Dostoyevsky, despite the astonishing innovations he brought to the novel, was no enemy of the past: he deeply admired "Don Quixote," and consciously borrowed from it for "The Idiot.") The plot is a higgledy-piggledy series of adventures, to which we might be tempted to apply the word “plotless” if the whole book didn’t so clearly and movingly lead up to its ending. That feeling which I mentioned in relation to "Wolf Hall," of being summarily ejected from an enticing and richly detailed world, is Don Quixote’s feeling when he recovers his sanity at the end of the novel. It is also our feeling when we are finally forced to take leave of him.

One of the many things Cervantes discovered was that he could repeatedly remind his readers that they were reading a book—could, in that sense, blatantly announce the fictionality of his fictional characters—and still get us to invest emotionally in these people and their story. There are apparently at least two sides to our minds in such cases: one which goes logically about its business, registering Sancho Panza’s jokes about typographical errors in previously published volumes of the knight’s adventures as patent admissions of the story’s fabrication; and another which takes Sancho, his master, and all the other characters at face value, allowing us to treat them as fellow humans, to laugh approvingly at Sancho’s earthy wisdom, to weep wholeheartedly at the Don’s death. We know the difference between reality and fiction (we are not, in that respect, as mad as Don Quixote), but that does not prevent us from feeling real emotions for these fictional characters. If anything, the fact that they sometimes comment on their own unreality makes them seem more real, as if they were capable of viewing their circumstances from the same perspective we do.

Cervantes was not the first writer to discover this for himself. There are numerous examples of it in his near contemporary Shakespeare. And if we go even further back, to the Middle English works of Geoffrey Chaucer, we can find an especially pure version of it—an easygoing, entirely comfortable readiness to acknowledge the related but different planes on which authors and characters dwell. To give but one example: Chaucer ends his extremely moving account of Troilus and Criseyde’s doomed love affair (a more sympathetic account, I would argue, than even Shakespeare’s version in "Troilus and Cressida") with the words

Go, litel bok, go litel myn tragedye . . .

. . . And kis the steppes, where as thow seest pace Virgil, Ovid, Omer, Lucan, and Stace

as if sending his poem out into the world in this literary ancestor-acknowledging manner won’t endanger or contradict the felt reality of his tale. As indeed it does not. What you might think of as the Wizard of Oz syndrome, that moment when the great and powerful Oz reveals himself as the little man working the effects from behind the curtain, can apparently coexist quite nicely with our continuing belief in the magic that little man produces.

Shakespeare is even braver than Chaucer in invoking this paradox, for he sometimes has his characters themselves deliver the envoi. At the end of "The Tempest," when Prospero is renouncing the sorcery that has enabled him to rule his island throughout the play—the magical powers that have in essence brought the play into being—he comes forward in his final speech and asks us for our applause without in any way breaking character. Even more riskily, in "Antony and Cleopatra," the doomed, captured Cleopatra, formerly the rebellious queen of Egypt and the proud mistress of Antony’s heart, deplores what she can already foresee as the result of her captivity: a future in which

. . . quick comedians Extemporally will stage us, and present

Our Alexandrian revels: Antony

Shall be brought drunken forth, and I shall see

Some squeaking Cleopatra boy my greatness

I’ th’ posture of a whore.

In Shakespeare’s own time, these lines would have been delivered by the boy actor playing the female part. In other words, this actor had to criticize his own squeaking delivery at the same time as he convinced the audience of the character’s palpable existence. And the character, through her lines, had to persuade us that this existence would in some ghostly form extend forever—allowing her as well as us to “see” this performance—even as its mortal version ended tragically, and at her own hands, less than two pages later in the script.

Theater, the art form which gave us the very notion of “suspension of disbelief,” specializes in such moments of contradiction. Real humans, just like us, are standing bodily before us onstage, representing actions and emotions that cry out for our sympathy, our hatred, our anxiety, our laughter, our distress. We do not really forget that they are actors, just as we don’t forget that the sets they occupy bear little or no relationship to reality, or that the lines they speak have been written for them by someone else. All these factors, far from being detrimental by-products, are built into the effectiveness of the theatrical form. As audience members, we are indeed in a suspended state, where real emotions about non-real events can course through us. But what is being suspended is not, precisely, disbelief. Logic, evidence, empirical truth: these elements that make up scientific belief, or even juridical disbelief, do not enter into it. We are not, as audience members, being asked to weigh in on the innocence or guilt, truthfulness or falsity, worthiness or unworthiness of the people we see before us onstage—not, at any rate, in the same way we would have to make such judgments in a courtroom. Our relationship to stage actors and the characters they represent is both more remote and less antagonistic than that. Precisely because we are not a jury of their peers, we can do things for them, and they for us, that would not be possible in our normal reality. For the two or three-hour duration of their performance, we give them life; and they, in turn, allow us to become pure vessels of feeling, afloat in a world that for the moment seems as real to us as one of our own dreams.

The theatrical work, in this sense, reinvents itself each time it is performed. However old the script may be, it impresses us with its newness, its aliveness to our own present circumstances, even as it confesses its embeddedness in the predetermined past. This is true, at any rate, of good theater. It all hinges on quality. And the same is true, though in a different way, if the literary work is a poem or a novel. What Chaucer succeeds in doing in "Troilus and Criseyde"—reminding us of the existence of his poetic ancestors and at the same time leaving us enthralled by the freshness of his verse tale— cannot be done by just anyone. Cervantes is not the only novelist who can call our attention to the book in our hands and still make it live for us, but he is the best of them. The level at which the trick is performed matters deeply. If it is good enough, it ceases to be deception. Formal ingenuity, practiced at this level, becomes almost transparent. Far from being an intrusion from the outside, the author’s intervention in his tale comes to seem an essential part of that tale.

One of the ways twentieth-century authors developed to remind us of their existence was the use of the footnote. What began as a sort of pseudo-scholarly addendum in T. S. Eliot’s “The Waste Land” had become, by the time of Nabokov’s "Pale Fire," a whole story in itself—an epic meant to rival and even eclipse the fragile literary work to which it was attached. After that came the essays and novels of David Foster Wallace, Nicholson Baker, Jonathan Lethem, and their many imitators, in which the footnote represented both a mimicry of academic style and a method of ironic self-commentary, so that to have second thoughts (and perhaps even third and fourth thoughts, each appropriately numbered on the page) was a way of signaling that some kind of thought was at any rate taking place. The typography of the footnote—the fact that it came in a different size from the regular type, often accompanied by a number, and always with a placeholder embedded in and noticeably interrupting the writing itself—appealed to these novelty-seeking litterateurs, as did its placement on the bottom of each page, usually with a thin half-line fencing it off from the text above. By reminding readers of the actual print technology through which the writer was communicating with them, these typographical oddities reinforced the sense that some kind of veil was being pierced; at the same time, the footnote offered opportunities for new veils, new masks and disguises, new ways in which the author could seem to argue with or undermine himself.

Yet this twentieth-century invention was not really new at all. One has only to look back to Jonathan Swift’s "A Tale of a Tub," composed in the late seventeenth century and first published at the beginning of the eighteenth, to find a similar game being played with footnotes. I do not recommend reading the whole of "A Tale of a Tub": like many of its twentieth-century descendants, it is so taken with the cleverness of its form that it disregards the problem of readable content. But the footnotes themselves can be a delight, as when Swift has his anonymous editor comment on the anonymous text, “I cannot guess the Author’s meaning here, which I would be very glad to know, because it seems to be of Importance.” Some of the notes are even embedded in little blank rectangles in the text itself, a format which the twentieth-century authors would surely have borrowed if they could, since it interrupts the tale even more pointedly than the normal kind of footnote.

You needn’t read far into "A Tale of a Tub" to get the point. In fact, the pinnacle of its self-undermining humor occurs a mere three or four pages into the text, where we are confronted with all the typographical elements battling together at once. A footnoting dagger-sign in the text is followed by four and a half lines of asterisks, amid which the words “Hiatus in MS.” are inscribed in smaller italic type. The text then resumes as before; but if we follow the dagger to its twin below, we get the Editor’s footnote:

Here is pretended a Defect in the Manuscript, and this is very frequent with our Author, either when he thinks he cannot say any thing worth Reading, or when he has no mind to enter on the Subject, or when it is a Matter of little Moment, or perhaps to amuse his Reader (whereof he is frequently very fond) or lastly, with some Satyrical Intention.

This single footnote is, to my mind, the best thing about "A Tale of a Tub," just as the best part of Swift’s equally clever (and equally impenetrable) "Battle of the Books" lies in the first sentence of its preface, where the again anonymous author proposes to define satire for us. “Satyr,” he says, “is a sort of Glass, wherein Beholders do generally discover every body’s Face but their Own; which is the chief Reason for that kind Reception it meets in the world, and that so very few are offended with it.” I think this comment goes a long way toward explaining why satiric authors like Don DeLillo and Thomas Pynchon were so loved by their late-twentieth-century audiences. It is not difficult to charm one’s readers when one seems, by giving them the wink, to include them in the inner circle of those who know better. Great satire, to last, needs to be offensive even to those who agree with it.

“A Modest Proposal” is Swift’s breathtaking achievement in this genre. Even now, nearly four hundred years after its first appearance, to read it is to be taken aback. It starts calmly enough, with potentially disturbing ideas masked in scrupulously inoffensive prose:

It is a melancholly Object to those, who walk through this great Town, or travel in the Country; when they see the Streets, the Roads, and Cabbin-doors crowded with Beggars of the Female Sex, followed by three, four, or six Children, all in Rags . . . I think it is agreed by all Parties, that this prodigious Number of Children in the Arms, or on the Backs, or at the Heels of their Mothers, and frequently of their Fathers, is in the present deplorable State of the Kingdom, a very great additional Grievance . . .

I think it is agreed: in that phrase lies the special brilliance of the voice that Swift has invented to put forth his little idea. A half-century before Adam Smith’s “invisible hand” and a century before Jeremy Bentham’s utilitarian doctrine, he has come up with the simple expedient of maximizing public good by eliminating any sentimental concern for the individual. It is all a matter of pounds, shillings, and pence: those who have money will buy the new product from those who do not, and everybody will measurably benefit all round. For “no Gentleman would repine to give Ten Shillings for the Carcase of a good fat Child; which, as I have said, will make four dishes of excellent nutritive Meat, when he hath only some particular Friend, or his own Family, to dine with him.” Swift goes on to suggest that, when the market fully emerges, butchers will proliferate to handle these mothers’-milk-fed year-old offspring of the poor—“although I rather recommend buying the Children live, and dressing them hot from the Knife, as we do roasting Pigs.”

You do not need to know anything about famine conditions in eighteenth-century Ireland or the political relations between the Irish and the English to find this little essay chilling (though that knowledge will certainly enrich your reading of certain lines). The voice speaks to us now, about our poverty, our wealth, our political championing of the national good, and our penchant to make welfare decisions in light of budgetary considerations. We are eating those babies still. And Swift is onto us: this is the writer-reader pact turned on its head, with all that cozy winking and mutual self-congratulation turned into something horrifying. What he invented, in “A Modest Proposal,” was not just that fatuously self-satisfied narrative voice, but the whole idea of a counterfactual work of nonfiction. This is what I meant when I said earlier that even an essay could be made up and also truthful. Swift’s essay is both, and we can still hear its gruesome honesty echoing down the corridor of four centuries.

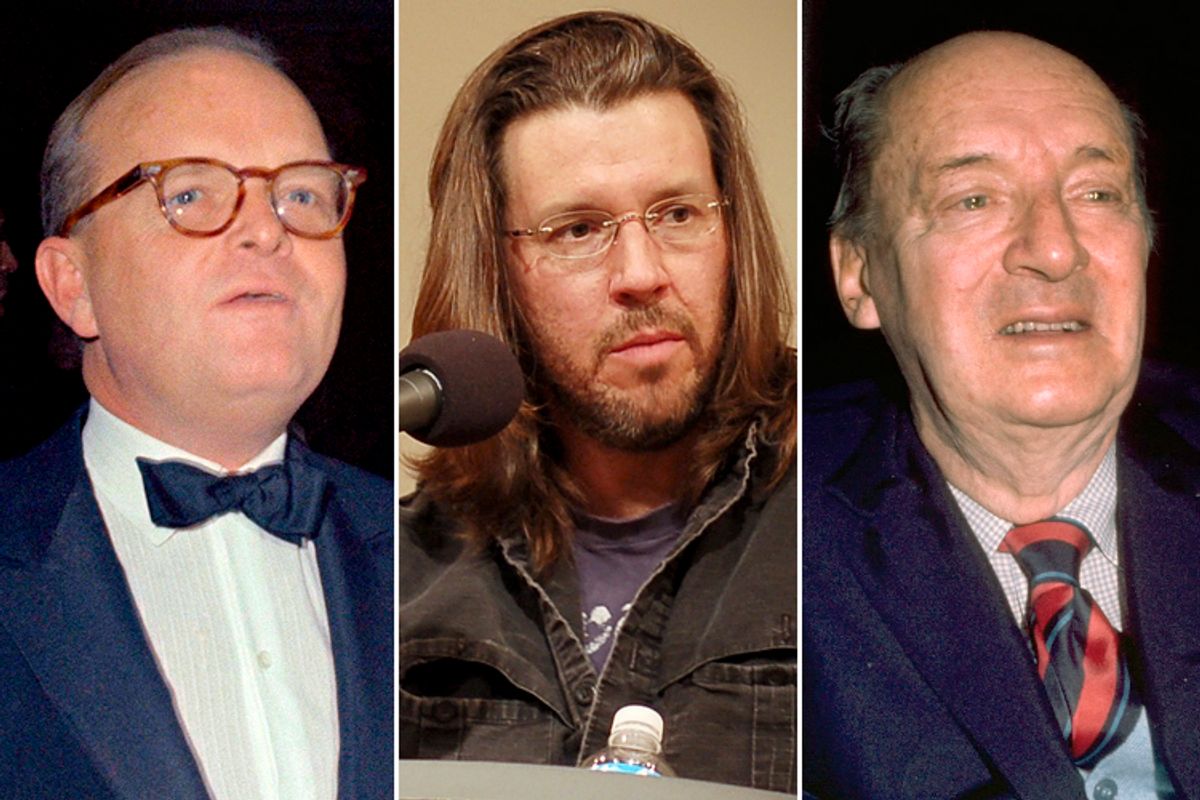

One can’t tell yet whether nonfiction novels like Truman Capote’s "In Cold Blood" and Norman Mailer’s "The Executioner’s Song" will last as long. Probably not, since very little literature endures as well as “A Modest Proposal” has. But I do not mean to criticize Mailer and Capote on this account. Their efforts to create a new genre that fit their own time were both brave and compelling. It is probably no coincidence that these two books, like Swift’s essay, dealt with the subject of murder, for that is a subject that habitually causes us to mingle lies with truths.

"In Cold Blood" came first chronologically, but it is "The Executioner’s Song" that has, over time, stayed with me as the greater book. My profound affection for Mailer, which stretches beyond this single work and covers much of his nonfiction writing, is something I can’t fully explain. I do not particularly care for war stories or boxing or Marilyn Monroe or ancient Egypt; I have little patience with masculine posturings about violence and sexual prowess. But there is something about Mailer’s voice that I have always loved—not the voice of the fiction, which often strikes me as crude and undeveloped, but the sinuous, chatty, abrasive, self-mocking voice of the essays and nonfiction books. Mailer can be just as crazy in his nonfiction as he is in his fiction (witness his bizarre theories about cancer, or about the communal need for blood revenge), but in the memoirs, essays, and political accounts, that craziness is couched in a prose style that knows itself better than we can ever know it. A good Norman Mailer sentence is a complicated work of art that can be unpacked in many ways, but at its heart there is always a simple mechanism: a two-way mirror that allows the author to reflect on himself even as we peer in at him.

The odd thing about "The Executioner’s Song" is that it manages to capture something of this reflective quality even though, for perhaps the first and only time in his nonfiction work, the author is utterly absent from its pages. In this case, the two-way mirror is there primarily for our benefit. If we are alert enough, we can see our avid, amoral selves reflected back at us even as we examine the ostensible subject: the murders committed in 1976 by Gary Gilmore, and the media circus that surrounded his execution. But this self-reflectiveness does not account for the full extent of the book’s value, nor for its allure. What makes it succeed as a narrative work of art is that Mailer, aided by his enormous respect for reality and history, is able to create credible literary characters out of actual people. This is not as easy as you might think. Read just about any news story about a killing or a trial and you will see what I mean, for in most cases all we get—if that—is a wisp or shred of character, a fleeting phrase or a single descriptive term. Only a novelist (as Janet Malcolm suggested) can really know about the interior lives of his characters; the nonfiction writers have to guess.

Malcolm happens to be one of the few writers whose journalistic characters, like Mailer’s, have the fullness of people in a novel. Yet her authorial voice couldn’t be more different from his. Where Mailer is loud and heated, Malcolm is subdued and cool. If he bodily intrudes on almost every situation he is observing—"The Executioner’s Song" is the great exception, in this regard—she tends instead to dwell in the shadows, emerging only intermittently. (I suppose "Iphigenia in Forest Hills" would be her equivalent exception, her single instance of placing herself onstage in the drama.)

I suspect I am drawn to them both for similar reasons, which may well be connected to the fact that all three of us are fascinated by murder stories. This preoccupation is not quite the same as the one that causes millions of people to consume mysteries (though I share that one, too). Mailer and Malcolm feed a somewhat different level of curiosity. The whodunnit aspect is relatively submerged in their work: we might know who the killer is from the very beginning of the story, or we might never find it out. Even the why remains relatively opaque, in a book like "The Executioner’s Song" or "The Journalist and the Murderer," because part of the point of each of these books is that we cannot hope to plumb the causes and motivations behind extreme violence. The central characters themselves, those characters who began as real people, do not appear to understand fully why they have done what they are accused of doing; they either cannot or will not explain it to our satisfaction. And yet we have a desperate desire to know.

That, among many other things, is what Malcolm’s and Mailer’s books are about—our readerly desire to penetrate what Joseph Conrad, in "The Secret Agent," wryly called the “impenetrable mystery . . . destined to hang for ever over this act of madness or despair.” Conrad’s wryness comes in large part from the fact that he is ostensibly quoting the overheated language of a newspaper account. (Another part of it, though, comes from the mere fact that he is Conrad: that kind of distance was always inherent in his worldview.) It is through newspapers that most of us get our first intimations of such murderous and self-murderous acts, so it should not be surprising that the news media themselves form a large part of the subject of both "The Journalist and the Murderer" and "The Executioner’s Song." Yet it is surprising, in that we have rarely witnessed it before. We have hardly ever seen the newsgathering telescope turned in both directions at once. That dual perspective, that capacity to look both outward and inward at once, is part of what makes Malcolm’s and Mailer’s works “novel” in both senses: new, and also fiction-like. The great authorial innovation, which is both structural and ethical, lies in turning the reflecting mirror back on the investigating press at the same time as the reader is forced to credit the discoveries of that flawed press—a category which includes, naturally, the author of the work in hand.

Something like that double-sided mirror also appears in the work of Roberto Bolaño, one of the few recent fiction writers who has been able to bridge the gap between overt formal invention and a steadfast investigation of human behavior. Bolaño, a Chilean novelist who died in 2003 at a very young but also very old fifty, was obviously a fan of the French surrealist poets and their often bizarre followers. In book after book, his characters club together to start literary movements whose main function appears to be to confound bourgeois expectations. As elements in the novels, we are offered meandering and incomplete plot summaries, digressive anecdotes that overwhelm their settings, ridiculous journal titles, cut-and-paste versions of poetry, and all manner of stylistic tics that cover the ground between piquant entertainment and purposeful tedium. Sometimes Bolaño’s novels even partake of these experimental quirks as well as describing them. But always, underneath, lies a recognizable, morally astute, amused but serious narrative voice which cares about the fates of specific characters. This is as true of the unfinished "Woes of the True Policeman"—whose central figure, Amalfitano, is one of the most appealing characters in all of Bolaño’s work—as it is of fully achieved novels like "Distant Star" and "By Night in Chile." And indeed, the fact that his final novel remains unfinished does little to damage its emotional impact on us, for it is in the nature of Bolaño’s fictional worlds that they trail off: incompletion is one aspect of their special kind of realism, just as our inability to know everything is one of the truths they leave us with.

If I had to name a single quality that makes Roberto Bolaño’s fiction compelling, it would be his capacity for stringent, hard-nosed sympathy. This is not the same as universal empathy or divinely inspired forgiveness or any of that softheaded nonsense. Bolaño is never blind to the crimes of humanity and of particular humans. They are, after all, his major subject. But he is able to create fictional works that enter equally into his own mind and the minds of others, even when those others are killers, or hypocrites, or madmen, or literary critics. It is not that he leaves behind notions of good and evil, but that he makes them seem inadequate as categories. There is a continuum that links his monsters and killers, on the one hand, and his writers and dreamers, on the other—or rather, a mirror, with those on opposite sides twinned in the reflective surface.

Overtly and covertly, the idea of twins and other paired figures pervades Bolaño’s universe. Sometimes he gives us a fictional stand-in for himself, a character named Arturo Belano. More often the narrator himself is a Bolaño-like figure who gets paired with someone else. At the end of "Distant Star," for instance—a short novel about a right-wing Chilean killer named Carlos Wieder, in which twins, mirrorings, and pairings have riddled the plot—the Bolaño-esque narrator is sitting in a café in Catalonia, reading Bruno Schulz:

Then Carlos Wieder came in and sat down by the front window, three tables away. For a nauseating moment I could see myself almost joined to him, like a vile Siamese twin, looking over his shoulder at the book he had opened . . . He was staring at the sea and smoking and glancing at his book every now and then. Just like me, I realized with a fright, stubbing out my cigarette and trying to merge into the pages of my book.

“Sympathy” is too paltry and flaccid a word for the state of mind this describes. It is a powerful and unwilled form of identification, a Houdini-like vanishing act that allows Bolaño to merge with his scariest and most repellent creations as much as with his likable ones.

Nowhere in his work is this strategy clearer than in "By Night in Chile," a short masterpiece published just three years before his death. The whole novel is a rant, or contemplation, or act of memory taking place in the mind of its main character, Father Urrutia Lacroix, also known as the literary critic H. Ibacache (he is his own twin, in other words, like all the other double-named villains in Bolaño’s work). Now on his deathbed, Father Urrutia is recalling his experiences as a Chilean literary figure before and after the coup. He thinks back on an encounter with Pablo Neruda; he remembers various figures of the left and (mostly) right; and he recounts— not just once, but three times—his glimpsed or imagined vision of the basement torture chamber where an American agent interrogated suspects during his wife’s literary salons. All of this is done in a vibrantly alive yet hushed voice that floats somewhere between willed stupidity and luminous knowledge, between self-communion and self-justification, between exhilaration and despair.

That there is indeed a hidden connection between despair and exhilaration is made explicit by a character in another novel, the female narrator of "Amulet": “And when I heard the news it left me shrunken and shivering, but also amazed, because although it was bad news, without a doubt, the worst, it was also, in a way, exhilarating, as if reality were whispering in your ear: I can still do great things; I can still take you by surprise, silly girl, you and everyone else...”

"Amulet," which was written immediately before "By Night in Chile," was like a dry run leading up to the greater work. Bolaño made two advances in the later novel: he put the narrative into the mouth of a dislikable character, and he eliminated himself entirely from the book. There is no Arturo Belano in "By Night in Chile." There is no Bolaño figure of any kind, unless we count the “wizened young man” of whom the priest seems so afraid, but he could be anybody, including Death. In "By Night in Chile," the author has finally done exactly what he feared so greatly in "Distant Star": that is, merged bodily with his most despicable character. Without even the separateness of “vile Siamese twins,” they have become a single person, a frightened and dying man living off the memories of his Chilean past, dreading the annihilation of himself and all his writings. There could be no character less like the real Roberto Bolaño than Father Urrutia—a member of Opus Dei, a smarmy literary careerist, a right-wing snob, a religious hypocrite, a worm in the service of Pinochet. And yet for the duration of "By Night in Chile" we are horribly and, yes, exhilaratingly inside him.

It is rightly said of W. G. Sebald, a writer with whom Bolaño is sometimes compared, that all his characters are essentially versions of their author. This, I think, is a flaw in his novels, particularly "Austerlitz," which purports to be about someone else. A similar flaw afflicts an even greater writer, Franz Kafka, whose strongest works are almost unbearable because of the airlessness of their self-enclosure. Roberto Bolaño is an author who risks exactly this charge and then triumphs over it. Finally, it is not that all his creations are projections of himself, but the opposite: in his novels, he becomes a mere figment of his characters’ reality, a shadow in their dreams. Like the French surrealist poets he so admires, he carefully sets up the trick mirrors, constructs all the cunning aesthetic parallels, assures us that he is playing with us— and then smashes the whole construction to bits. When the dust clears, all that’s left (but it is more than enough) is a moment of true feeling.

The desire to innovate is not what lies at the heart of books like these. If it were, they would feel much flimsier, morally and aesthetically, than they do. In each case, the author’s primary aim is to reveal the truth, and the novelty of form is just a by-product of that aim. This is the paradox that lies behind formal inventiveness: you can only achieve an exemplary kind of novelty if it is not, primarily, what you are trying to achieve. As an end in itself, stylistic innovation is merely a way of showing off, a useless if mildly entertaining trapeze act; only when harnessed to the author’s fervent truth-telling does it become significant.

To tell the truth in literature, each era, perhaps even each new writer, requires a new set of authorial skills with which to rivet the reader’s attention. We are so good at lying to ourselves, at lapsing into passive acceptance, that mere transparency of meaning is insufficient. To absorb new and difficult truths, we need the jolt offered by a fresh style. Yet what is startling at first eventually hardens into either a mannerism or a tradition. Even Swift’s “A Modest Proposal,” if read too early and too often (in a classroom setting, say), can come to seem a mere example of Satire. So every writer—every good writer, every writer who really has something to say—must figure out for herself a new form in which to say it. The figuring need not be conscious, and the innovation need not be dramatic or obvious; we can be affected by style without necessarily perceiving the sources of the effects. But if we do perceive them, they cannot detract from our sense of the writer’s seriousness (a seriousness that, in the case of an innovator like Mark Twain, may partake of a great deal of humor). The structural and stylistic eccentricities must seem—and be— essential, not merely ornamental.

Excerpted from "Why I Read: The Serious Pleasure of Books" by Wendy Lesser, published in January 2014 by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, LLC. Copyright © 2014 by Wendy Lesser. All rights reserved.

Shares