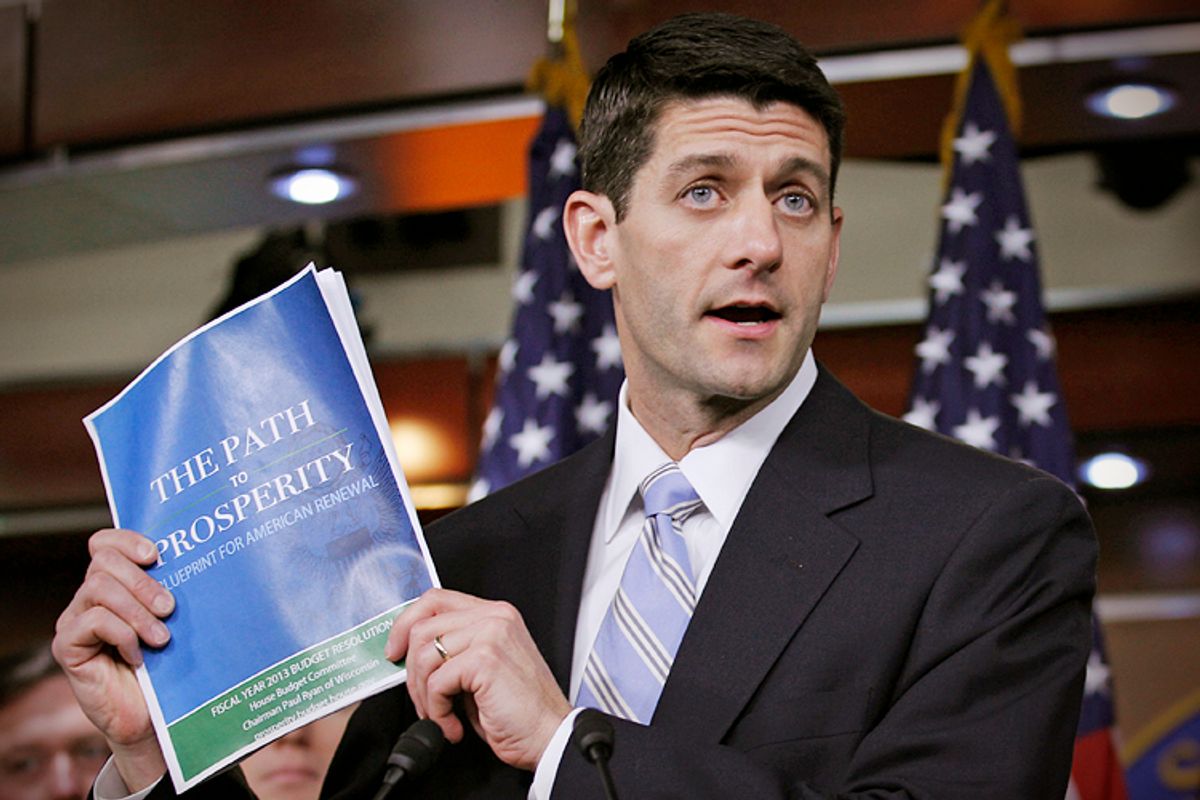

House Budget Committee Chair Paul Ryan’s new report on safety net programs and poverty is disappointing. Though it purports to be a balanced, evidence-based review of the safety net, it falls far short of that standard. It’s replete with misleading and selective presentations of data and research, which it uses to portray the safety net in a negative light. It also omits key research and data that point in more positive directions.

For several years now, Ryan (R-Wisc.) has proposed annual budgets that would deeply cut programs for the poor. The Ryan budgets have consistently secured between 60 and 67 percent of their budget cuts from programs for low- or moderate-income people. The true test of Ryan’s forthcoming budget with regard to poverty will lie in whether it follows past practice and targets programs for less-fortunate Americans for the lion’s share of its savings. Unfortunately, the new report may be, in part, an effort to lay a framework for severe cuts in low-income programs once again.

The report substantially understates both the nation’s progress in reducing poverty over the past 50 years and the safety net’s impact today.

* The report features the “official” poverty measure even though analysts across the political spectrum — and all three witnesses at a recent hearing that Ryan held, including the two Republicans he invited — have warned that the official poverty measure is deeply flawed for tracking changes in poverty over recent decades and for evaluating the impact of the safety net today. The official measure ignores a very large share of the safety net — including SNAP (formerly known as food stamps), tax-based benefits such as the Earned Income Tax Credit and Child Tax Credit, and low-income housing assistance, among other programs. Using a more comprehensive measure of poverty that analysts broadly favor, known as the Supplemental Poverty Measure (SPM), Columbia University researchers recently found that poverty had fallen markedly, from 26 percent in 1967 to 16 percent in 2012. Ryan buries this fact, failing to note the deep reductions in poverty under the SPM since the 1960s until page 201 of his report.

* Moreover, the SPM shows that in 2012, the safety net cut poverty nearly in half — shrinking the poverty rate from 29 to 16 percent. Yet in its 200-plus pages, the Ryan report fails to mention these findings. The report similarly glosses over the role of Medicaid and CHIP in reducing the numbers of uninsured. For example, nowhere does the report note that due to these programs, the share of children who are uninsured has now reached an all-time low.

The report overstates both the marginal tax rates that most low-income families face and their impact.

* The report argues that much of the safety net creates a “poverty trap” because “some” families can face marginal tax rates (the rate at which a family loses benefits as its earnings rise) of “nearly 100 percent” and that these high tax rates discourage people from working. The report fails to explain that very few families face marginal tax rates this high. It also fails to acknowledge that the leading research in the field does not support the contention that the safety net creates a poverty trap that does more harm than good.

* A new study by Johns Hopkins University economist Robert Moffitt, one of the leading scholars in the field, examines marginal tax rates for recipients of SNAP and other programs and concludes that high marginal tax rates are a significant problem “only for a small portion of the SNAP caseload.”

* Moffitt and two other researchers reviewed the research on the safety net’s overall impact on poverty, specifically taking work disincentives into account. They found that after accounting for these effects, the safety net remains highly effective at reducing poverty, cutting the number of people in poverty by about half.

The report criticizes Medicaid and health reform for discouraging work, but it ignores how health reform significantly reduces work disincentives for working-poor parents.

* The report cites two reports from the early 1990s that suggest parents on Medicaid were less likely to work, presumably because if they worked and their earnings exceeded the Medicaid eligibility limit, they would become uninsured. But, the Ryan report ignores the fact that health reform sharply reduces these Medicaid work disincentives for parents. As we’ve previously explained, before health reform’s coverage expansions took effect this year, Medicaid eligibility for working parents ended in the typical state at just 61 percent of the poverty line; once parents’ earnings climbed above that level, they could become uninsured. Today, in states implementing the Medicaid expansion, low-income parents remain eligible until their incomes equal 138 percent of the poverty line and, if their income rises farther, they can receive subsidies to purchase coverage in the new health insurance exchanges. Health reform thus addresses the very same Medicaid work incentive issue for parents that the report raises. Yet the report never mentions it, portraying health reform and its effects on work solely in a negative light.

The report ignores other important research that undercuts its assertions.

* The report distorts research on the 1996 welfare law. The report implies that the increase in single parents’ labor force participation and the decline in child poverty in the 1990s were overwhelmingly due to that law. However, a highly regarded study by University of Chicago economist Jeffrey Grogger found that welfare reform policies such as time limits and work requirements accounted for just 13 percent of the total rise in employment among single mothers in the 1990s. The Earned Income Tax Credit (which policymakers expanded in 1990 and 1993) and the strong economy were much bigger factors, accounting for 34 percent and 21 percent of the increase, respectively.

* The report misrepresents data and research on “deep poverty.” The report never acknowledges research showing that, while the welfare law increased employment, it also increased the share of mothers and children living in deep poverty. Nor does the report acknowledge that SNAP, of which the report is critical, shrinks the number of children below half of the poverty line by 30 percent, from 4.9 million to 3.5 million in 2012, using the SPM.

• The report omits important research showing that Head Start has long-term positive impacts for children. The report focuses on research that shows that gains from Head Start fade during elementary school. But, important research by Harvard’s David Deming shows that gains re-emerge over time — that children who attend Head Start are less likely to be out of school and out of work, and less likely to be in poor health, years later.

* The report sometimes uses data to imply that a program isn’t working when the data likely means the program is serving a very disadvantaged population. For example, the report says that people enrolled in both Medicaid and Medicare are in worse health than other seniors who receive Medicare alone, implying that Medicaid is harmful to health. That’s deeply misleading. People eligible for both Medicare and Medicaid are a considerably sicker group; they are, for example, more likely to be receiving expensive longterm care services such as nursing home care — since Medicare does not cover long-term care.

To be sure, the nation has not made as much progress over the last 50 years as policymakers hoped when President Johnson declared war on poverty, and various programs and policies can stand improvement. But, the Ryan report is far from a fair and balanced presentation of the data and research evidence.

Shares