Here's a bold plan for rape prevention. Let's try not raping anybody.

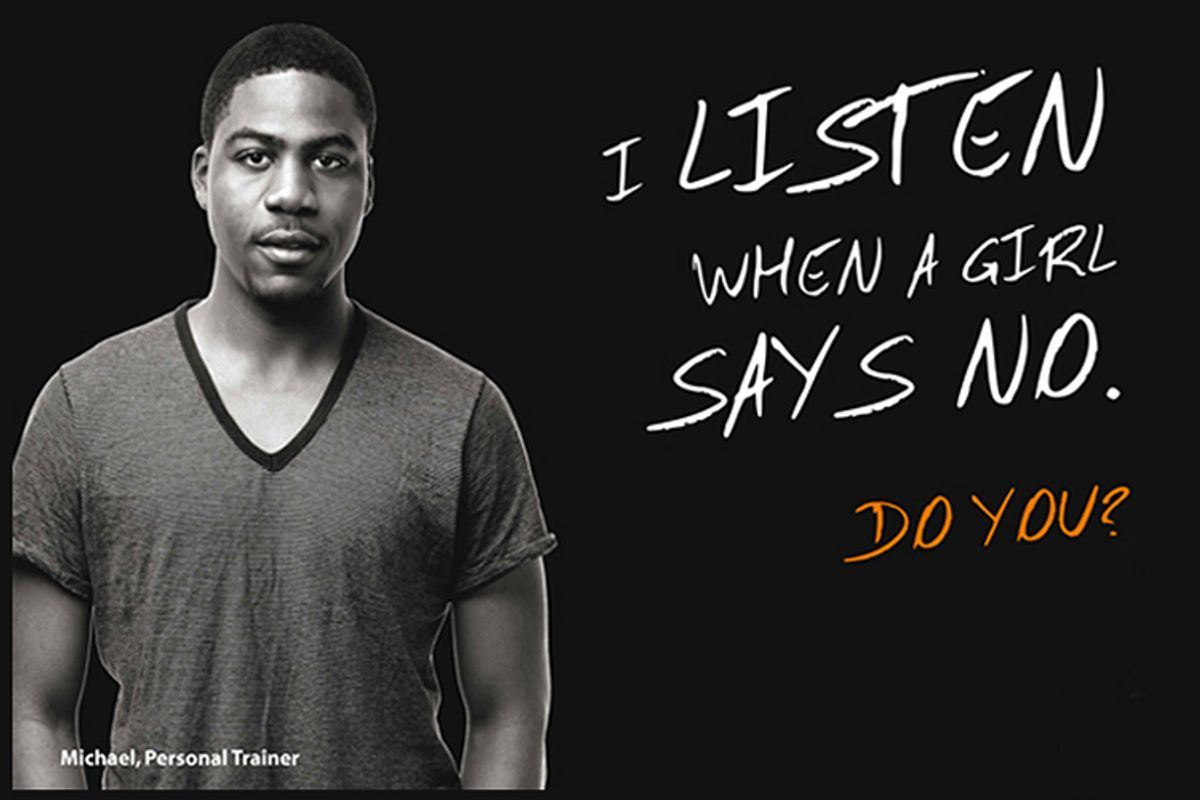

In Scotland Monday, police announced a new awareness campaign aimed not at potential victims – as plenty of campaigns traditionally do -- but squarely at potential offenders. The month-long campaign aims to teach men and women both straight and gay about the changes in Scottish rape law and what constitutes consent. With simple bold images, a variety of men are depicted with challenges like, "I'm the kind of guy who doesn't have sex with a girl when she's too drunk. Do you?" "I listen when a guy says no. Do you?" and I know when she's asleep it's a no. Do you?" On its site, the We Can Stop It campaign explains the updated changes to the law, including explicit definitions of consent, and the fact that a "victim can be male or female."

The definition of what constitutes rape, or "legitimate" rape as it has sometimes been fancifully known, can be confusing. Here in the U.S., laws vary from state to state. After schoolteacher Lydia Cuomo was anally and orally sexually assaulted by an off-duty cop in 2011, she campaigned – unsuccessfully -- to have the definition of rape changed in New York state. And under current Scottish law, rape is defined as "when a person intentionally or recklessly penetrates another person’s vagina, anus or mouth with their penis" – which narrows rape to something only a man can do, and only with his sexual organ. (I'm sure everyone who's ever been sexually abused by a female, or with an object other than a penis, will be super-relieved to know that at least in Scotland what happened to them wasn't a rape.)

Despite the limitations of Scottish law, though, the push to educate men is a necessary and powerful one. According to the BBC, "Police say one-in-six rapes takes place when the victim is asleep, and more than 90% are carried out by someone known to the victim." Those are astonishing numbers. It's pretty clear that helping men understand that not saying no does not mean saying yes, and that a person who was not actively fighting you off can still be a person you've sexually assaulted, is a cause worth fighting for.

The idea that the burden of preventing rape falls not just on the shoulders of potential victims is still a relatively new one. When Zerlina Maxwell suggested on Fox’s “Hannity” last year that "I think we should be telling men not to rape women and start the conversation there," she received a scathing response from critics. But as she eloquently put it, "You’re talking about this as if it’s some faceless, nameless criminal, when a lot of times it’s someone you know and trust. If you train men not to grow up to become rapists, you prevent rape." And as musician Henry Rollins bluntly asked after the Steubenville verdict, "What made these young people think that that what they did was OK?"

The prevailing notion of a rapist as the knife-wielding thug hiding in a dark alleyway does not bear out the experience of many survivors. Rapists are husbands and boyfriends and neighbors and people we trust and let into our lives -- which means that many of them are guys who can and must be encouraged to behave respectfully and responsibly before they're in a situation they don't understand the consequences of. Having men give the message to other men, in a manner that challenges without blame or shame, is a positive and effective way of changing the conversation around sexual assault for the better. And it works. The new Scottish campaign is similar to one launched in Canada a few years ago with the simple recurring message, "Don’t Be That Guy." In the wake of the public awareness push, sexual assault rates soon dropped dramatically.

Telling men not to rape seems like such a simple idea it's easy to dismiss it. It seems like it's politely asking muggers to stop snatching iPhones. Or worse, it gets twisted by "anti-feminism" groups as an attack on male behavior. But rape is a crime that rarely happens in a vacuum. And whenever there's an opportunity to replace ignorance with information, we have the chance to prevent somebody from becoming a victim – and somebody else from becoming a victimizer. As Major Crime and Public Protection Assistant Chief Constable Malcolm Graham explains, "There are a wide range of circumstances around each case – but the common factor is that where there is no consent, it is rape."

Shares