The fact that GDP growth in the United States currently outpaces European growth by a large margin might lead one to believe that America’s economic future is brighter than Europe’s. Nothing could be farther from the truth.

The fact that GDP growth in the United States currently outpaces European growth by a large margin might lead one to believe that America’s economic future is brighter than Europe’s. Nothing could be farther from the truth.

Despite all the reflexive triumphalism, the U.S. economy has produced poor investment and wage outcomes for a generation. Meanwhile, northern European economies have achieved something that increasingly eludes the United States – a growing middle class.

Remember the famous line “I’ll have what she’s having” from the movie “When Harry Met Sally”? It is apt in our context: Americans need what northern Europeans have.

There are those who argue that making this point amounts to heresy. After all, the European Union is struggling to reorder its flawed architecture, stabilize public debt and, most important, regain a decent pace of economic growth.

Yet beneath those daunting challenges, the seasoned and potent internal institutions, crafted in the postwar years in northern Europe to broadcast prosperity widely, continue to function smoothly.

U.S. obsession with quarterly capitalism

Unfamiliar to Americans, these corporate governance and wage systems have succeeded precisely because they reject the American executive incentive structure. Europeans have studiously not embraced what Nobel Laureate Edmund Phelps has called “short-termism.”

At the core is the continuing U.S. obsession with quarterly capitalism. This is an unnatural focus for any business that can be explained only by the fact that a stock-optioned management is focused on near-term performance.

But its real life effects are truly problematic: For example, if that means being parsimonious with corporate outlays for R&D, wages, investment and the like in order to spike quarterly earnings, so be it.

In the U.S. model, what matters is not the long-term success of the company, but one’s own ability to extract maximum personal benefits while one is along for the ride. That is a most rudimentary form of capitalism, one that may compete with Manchester capitalism for the trophy in wrong-mindedness.

Europe does well

Let’s look at specifics and begin with productivity, the most important economic indicator of economic prowess. Since 1979, annual productivity per hour worked in northern Europe has grown one-third faster than in the United States year in and year out. Equivalence now exists on the factory floor in the United States, France and the Low Countries.

Weak U.S. investment is the most conspicuous reason. In a big change from the postwar years, investment by non-financial firms in Australia and northern Europe has outrun investment by U.S. firms in recent decades, as documented by Eurostat economists in 2009.

U.S. net investment is less than one-half the level it was in the late 1980s. Studies document that U.S. managers apply excessive discount rates when evaluating future investments. They do so by screening out worthwhile options, due to inappropriately short investment time-horizons compared to managers in these other rich countries.

An error to blame globalization

Quarterly capitalism arose in the United States from the incentive structure created by inept attempts in the 1970s and 1980s to address the age-old “agency problem.” According to that, management prioritizes returns by what it means for executive suites rather than for shareholders.

The unintended consequence of the solution manifests itself today in the weak corporate boards of publicly held U.S. enterprises.

In a short-term world, higher wage bills also affect corporate bottom lines, just like higher investment and R&D outlays. Unlike European counterparts, U.S. enterprises have made it their cause to compress wages. They have done so by weakening unions and by offshoring. (I have detailed this delinking of wages from rising productivity in my book "What Went Wrong.")

That decoupling has not occurred in Australia or northern Europe. Indeed, comprehensive employer labor costs and wages have grown roughly apace with productivity there. They now average $10 per hour more in purchasing power parity terms than in the United States.

Globalization is erroneously blamed for U.S. wage compression. That is an argument belied by the fact that higher-wage northern European nations are considerably more engaged in cross-border trade than is the United States.

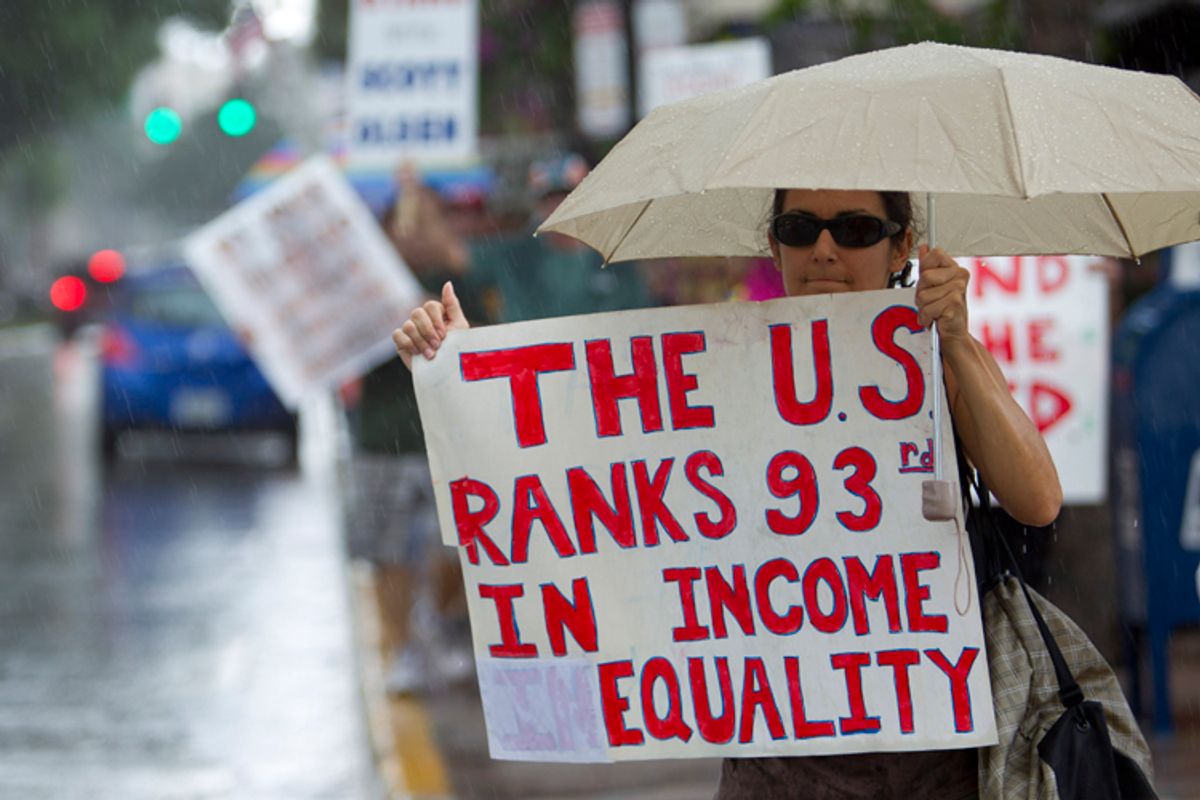

OECD statistics show that the top 10% of Americans receive $16 dollars in income for every $1 received by the lowest tenth. That is more skewed than the income distribution in Portugal and nearly comparable to Turkey, two economies dominated by thin layers of the affluent. The distortion of U.S. income distribution is twice as severe as any other rich democracy.

Improve skills and change corporate governance

In a short-term world, human capital investment can also be seen as a drain on bottom lines. Accordingly, U.S. firms have come to eschew up skilling, in stark contrast to nations abroad. That is why Australia and every nation in northern Europe has leapfrogged the United States to now have more skilled workforces, in contrast to the situation in 1998.

The ability of Australia and the northern European economies to broadly deliver rising real incomes during the era of globalization dramatized the American failure to do so.

The key remedy is to change the prevailing incentive structure. This would require confronting U.S. management with the architecture of northern European corporate governance and ending short-termism.

This would also mean adopting the successful German codetermination governance model in which employees sit on corporate boards (ironically, an innovation imposed by British and American officials in the early post-WWII era).

Viewed over the longer haul, as opposed to isolated annual quarters, corporate owners and shareholders will benefit from higher returns that result from higher investment, including in the workforce.

A healthy byproduct of codetermination has been higher wages, as nations across northern Europe have adopted local variations of the Australian wage determination mechanism, which links wages to rising productivity year after year.

Americans are fortunate to have well-tested models abroad to rectify the deficiencies of their own quarterly capitalism. The question is whether the American genius for adapting new technologies extends to practices from across the globe.

Doing so requires acknowledging that other countries’ models have something to offer and then overcoming resistance from those who benefit most from the current allocation of gains from growth.

Game on, American people.

Shares