The conservative book industry is dying, says BuzzFeed's McKay Coppins. That sounds like a ripe topic for some schadenfreude, if it's actually true. There is some amusing information in the piece, like the fact that Jeb Bush's big immigration book sold fewer than 5,000 hardcover copies. But Coppins uses the screwed-up economics of publishing books by (or "by") politicians to illustrate what he claims are the larger problems of the conservative book industry, when it is proof mainly that it's not worth it to give any politician a book advance of any size.

Still, things are apparently dire. Longtime conservative editors are despairing. It is "increasingly difficult to turn a profit on midlist books." The death of the exurban bookstore chain has depressed sales. Insiders worry that the entire market is "an overcrowded field of preachers feverishly contend[ing] for the attention of the same choir."

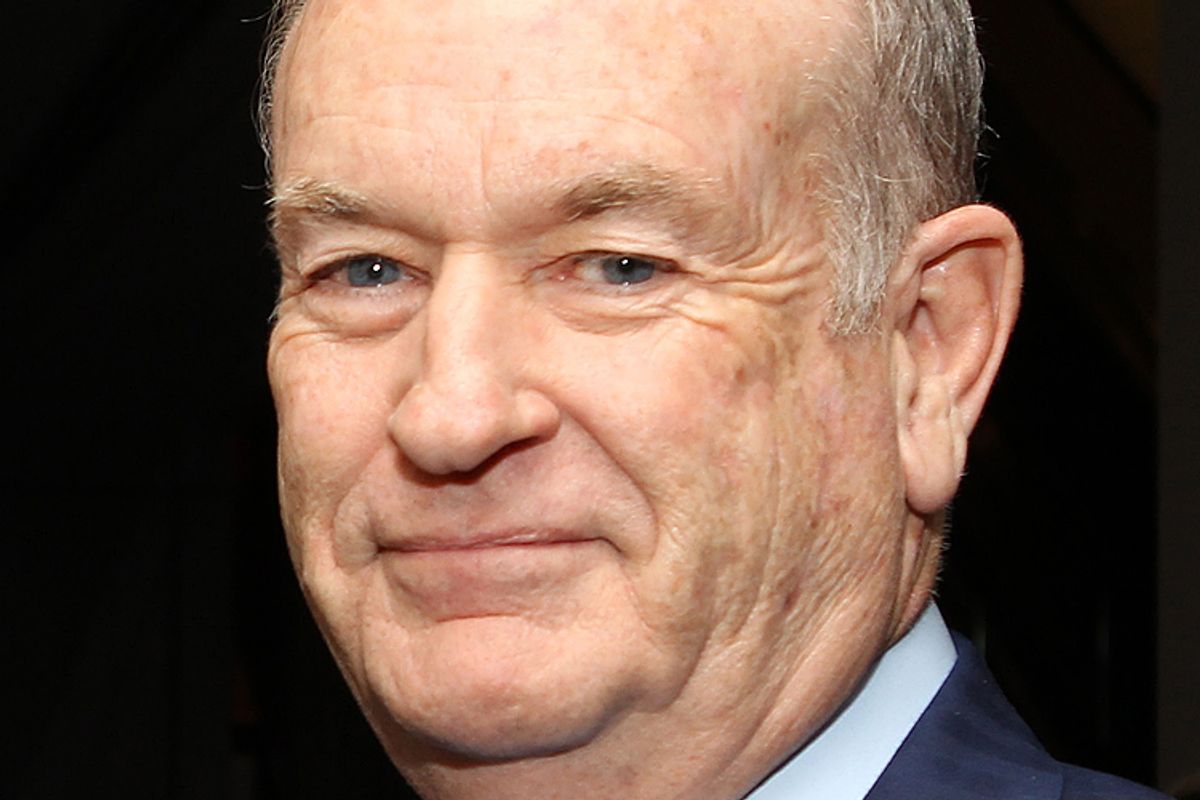

Are we actually at the end of the "gold rush," though? While the audience is not exactly growing, conservative books still sell well. Bill O'Reilly's "Killing Jesus" and Charles Krauthammer's amusingly titled "Things That Matter" were two of the best-selling books of 2013, and both are still on the Times Best Sellers list. Conservative books have also always benefited from a well-oiled promotional machine that frequently includes bulk sales and "book clubs." That machinery still exists, and still helps prop up books that couldn't otherwise survive in the supposed marketplace of ideas. (Writers for Regnery, the right-wing publishing house that helped start the modern conservative book industry, sued it in 2007 for depriving them of royalties by selling books at steep discounts to book clubs and giving them away to newsletter subscribers. The dubious argument behind the suit was that those books would have sold nearly as many copies, at full retail price, through traditional retail means.)

While conservative publishing may be on the decline -- like all publishing, and for most of the same reasons -- it's decidedly not yet dead. The actual problem Coppins highlights in his story is that conservatives now believe that there are too many conservative books and that most of them aren't very good, and they blame this on "the genrefication of conservative books," meaning the fact that they are usually published by imprints and marketed differently from "regular" hardcover nonfiction books. This was initially supposed to be a positive development, but, alas:

Many of the same conservatives who cheered this strategy at the start now complain that it has isolated their movement’s writers from the mainstream marketplace of ideas, wreaked havoc on the economics of the industry, and diminished the overall quality of the work.

While for years explicitly conservative books (that is, books marketed to movement conservatives) were mainly published by independent houses like Regnery, the biggest publishing companies all fell all over each other to start their own conservative "imprints" in the late 1990s and early 2000s to capitalize on the fact that crappy conservative books sold really, really well. This was apparent way back in 1992, when Simon and Schuster made a mint on Rush Limbaugh's "The Way Things Ought to Be." (Simon and Schuster has stuck with Rush, also publishing his most recent literary work, "Rush Revere and the Brave Pilgrims: Time-Travel Adventures With Exceptional Americans.") The publishers started separate imprints for these books in part because they were embarrassed to have their prestigious brands tainted by them, but also because conservative books generally couldn't meet most publishing companies' (already lax) standards of quality and accuracy.

The problem is not that shunting conservative books off into imprints somehow caused conservative books to become worse and fail to appeal to people outside the shrinking world of dedicated movement conservatives. The problem is that conservatives are embarrassed by which sort of conservative books conservative audiences actually want to buy and read. Conservatives don't want to read good, smart books. They mostly want to read Fox and talk radio hosts writing about presidents. What's "killing" conservative books seems to be embarrassment.

Which is understandable. The right likes to think that intellectuals and academics like Allan Bloom and Dinesh D'Souza spurred the explosive growth of movement conservatism in the 1980s and 1990s, when it was actually mostly Rush Limbaugh. That's a harmless belief when you're winning, but when you're facing death by long-term demographic trends, you reexamine the people you've yoked yourself to. Right-wing intellectuals imagined breaking into mainstream publishing would lead to a thousand "The Closing of the American Minds" and "God And Man At Yales." Instead, it's Rush Revere and "Liberal Fascism." Conservative books are bad for the same reason that talk radio and the Washington Examiner aren't as high-quality as the New York Times and NPR: The movement is rotten, and held together mainly by resentments that are dying out with the Silent Generation. Those who most loudly stoke those resentments -- or those who simply appeal to that generation's sour nostalgia -- sell the most copies.

Conservatives frequently complain of being frozen out of the culture industry, though, like all industries, the culture industry will produce or sell anything it expects to profit from. There is actually plenty of room for conservatives in film, music, television and publishing -- the biggest publishers in the world have been selling books by conservative pundits for years -- and if conservatives don't like the products they themselves create and sell to one another, they can't exactly blame the liberal media.

Shares