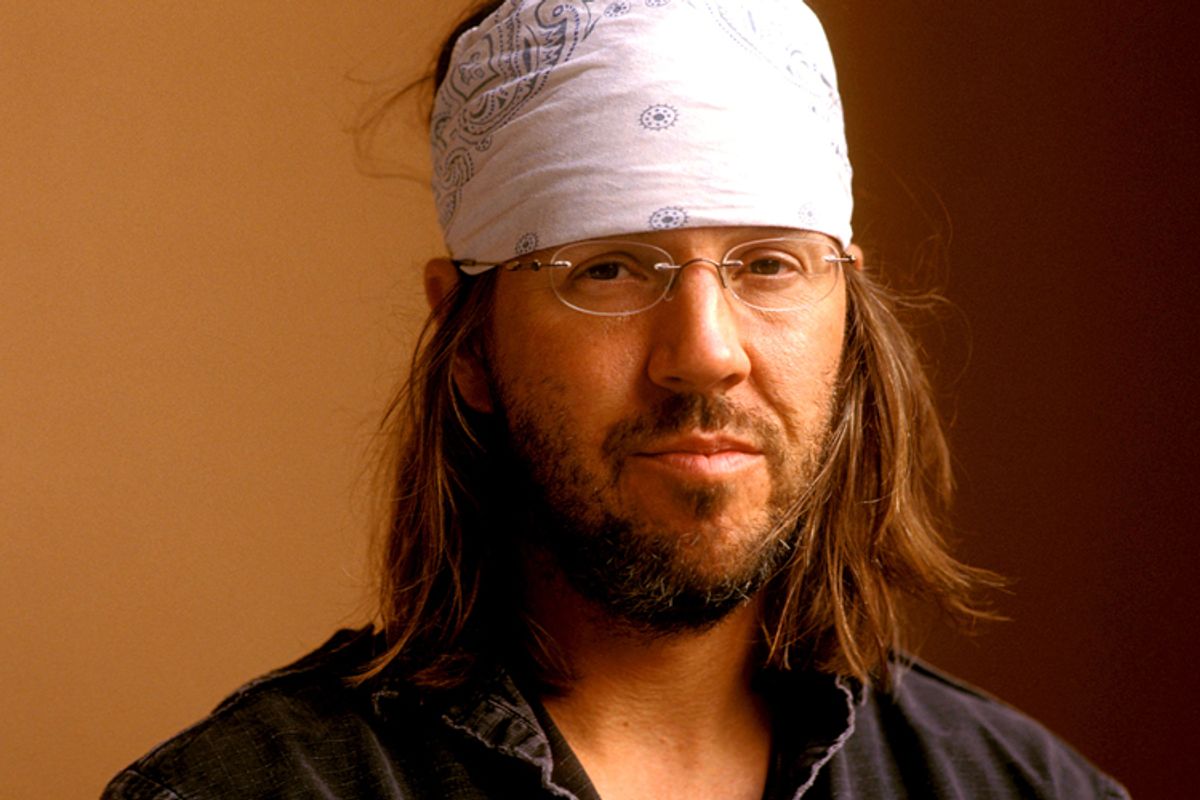

Percy Shelley famously wrote that “poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world.” For Shelley, great art had the potential to make a new world through the depth of its vision and the properties of its creation. Today, Shelley would be laughed out of the room. Lazy cynicism has replaced thoughtful conviction as the mark of an educated worldview. Indeed, cynicism saturates popular culture, and it has afflicted contemporary art by way of postmodernism and irony. Perhaps no recent figure dealt with this problem more explicitly than David Foster Wallace. One of his central artistic projects remains a vital question for artists today: How does art progress from irony and cynicism to something sincere and redeeming?

Twenty years ago, Wallace wrote about the impact of television on U.S. fiction. He focused on the effects of irony as it transferred from one medium to the other. In the 1960s, writers like Thomas Pynchon had successfully used irony and pop reference to reveal the dark side of war and American culture. Irony laid waste to corruption and hypocrisy. In the aftermath of the '60s, as Wallace saw it, television adopted a self-deprecating, ironic attitude to make viewers feel smarter than the naïve public, and to flatter them into continued watching. Fiction responded by simply absorbing pop culture to “help create a mood of irony and irreverence, to make us uneasy and so ‘comment’ on the vapidity of U.S. culture, and most important, these days, to be just plain realistic.” But what if irony leads to a sinkhole of relativism and disavowal? For Wallace, regurgitating ironic pop culture is a dead end:

Anyone with the heretical gall to ask an ironist what he actually stands for ends up looking like an hysteric or a prig. And herein lies the oppressiveness of institutionalized irony, the too-successful rebel: the ability to interdict the question without attending to its subject is, when exercised, tyranny. It [uses] the very tool that exposed its enemy to insulate itself.

So where have we gone from irony? Irony is now fashionable and a widely embraced default setting for social interaction, writing and the visual arts. Irony fosters an affected nihilistic attitude that is no more edgy than a syndicated episode of "Seinfeld." Today, pop characters directly address the television-watching audience with a wink and nudge. (Shows like "30 Rock" deliver a kind of meta-television-irony irony; the protagonist is a writer for a show that satirizes television, and the character is played by a woman who actually used to write for a show that satirizes television. Each scene comes with an all-inclusive tongue-in-cheek.) And, of course, reality television as a concept is irony incarnate.

For the generation that came of age during Vietnam, irony was the response to a growing distrust toward anything and everything. In the 1980s, academics such as Mark Jefferson attacked sentimentality, and Neo-Expressionists gave sincerity a bad name through their sophomoric attempts at heroic paintings. Irony was becoming a protective carapace, as Wallace pointed out, a defense mechanism against the possibility of seeming naïve. By the 1990s, television had co-opted irony, and the networks were inundated with commercials using “rebel” in the tagline. Take Andre Agassi’s Canon camera endorsement from that period. In the commercial, the hard-hitting, wiseass Agassi smashed tennis balls loaded with paint to advertise Canon’s “Rebel” brand camera. The ad wraps with Agassi standing in front of a Pollockesque canvas saying “Image is everything.” For all the world, it seemed rebellion had been usurped by commercialism.

This environment gave artists few choices: sentimentality, nihilism, or irony. Or, put another way, critical ridicule as experienced by the Neo-Expressionist (see Sandro Chia), critical acceptance through nihilism like Gerhard Richter, or critical abdication through ironic Pop Art such as Jeff Koons. For a while, it seemed no new ideas were possible, progress was an illusion, and success could be measured only by popularity. Hot trends such as painted pornography; fluorescent paint; sculpture with mirrors, spray foam, and yarn were mistaken for art because artists believed blind pleasure-seeking could be made to seem insightful when described ironically.

* * *

Recently, the Onion spoofed an ad campaign in which Applebee’s encouraged hipsters to visit their restaurants “ironically” and middle-aged adults to make fun of hipsters. The parody describes four “with it” young folks “seriously” eating their dinner at Applebee’s while ridiculing the food, service and atmosphere. Behind them sit three sad, middle-aged adults mocking the hipsters, sarcastically saying “because I know who the latest bands are I am too cool to eat a cheeseburger without making fun of it.” Neither group is genuinely happy about their meal or station in life. The Onion’s satire points out that irony and formality have become the same thing. At one time, irony served to reveal hypocrisies, but now it simply acknowledges one’s cultural compliance and familiarity with pop trends. The art of irony has lost its vision and its edge. The rebellious posture of the past has been annexed by the very commercialism it sought to defy.

Early postmodernists such as Robert Rauschenberg broke the modernist structure of medium-specificity by combining painting and sculpture. The sheer level of his innovation made the work hopeful. However, renegade accomplishments like Rauschenberg’s gave way to an attitude of anything-goes pluralism. No rules governed the distinction of good and bad. Rather than opening doors, pluralism sanctioned all manner of vapid creation and the acceptance of commercial design as art. Jeff Koons could be seen as a hero in this environment. Artists became disillusioned, and by the end of the 1980s, so much work, both good and bad, had been considered art that nothing new seemed possible and authenticity appeared hopeless. In the same period, a generation of academics came of age and made it their mission to justify pluralism with a critical theory of relativism. Currently, the aging stewards of pluralism and relativism have influenced a new population of painters, leaving them confused by the ambitions of Rauschenberg. Today’s painters understand the challenging work of the early postmodernists only as a hip aesthetic. They cannibalize the past only to spit up mad-cow renderings of “art for no sake,” “art for any sake,” “art for my sake” and “art for money.” So much art makes fun of sincerity, merely referring to rebellion without being rebellious. The paintings of Sarah Morris, Sue Williams, Dan Colen, Fiona Rae, Barry McGee and Richard Phillips fit all too comfortably inside an Urban Outfitters. Their paintings disguise banality with fashionable postmodern aesthetic and irony.

Likewise in contemporary fiction, Tao Lin has made a reputation off reproducing disaffected, hipster malaise. In "Shoplifting from American Apparel," Lin inserts himself as the protagonist Sam, a vegan writer who lives in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. Sam often feels vaguely “fucked” in a generally affectless world of name brands, Gchat and Facebook. He shoplifts a couple times and winds up in jail for a night. Occasionally, he mindlessly mistreats others for a laugh: inexplicably throwing a friend’s drink, hitting someone with a stick, and ordering someone to jump over a bush. The entire narrative is as disconnected from the larger society as the characters are from each other, and therefore it reads as a mimetic rendering of a soulless world rather than satire. New Tao Lins publish every day, feeding the culture’s desire to watch its own destruction.

But David Foster Wallace predicted a hopeful turn. He could see a new wave of artistic rebels who “might well emerge as some weird bunch of anti-rebels… who dare somehow to back away from ironic watching, who have the childish gall actually to endorse and instantiate single-entendre principles… Who eschew self-consciousness and hip fatigue.” Yet Wallace was tentative and self-conscious in describing these rebels of sincerity. He suspected they would be called out as “backward, quaint, naïve, anachronistic.” He didn’t know if their mission would succeed, but he knew real rebels risked disapproval. As far as he could tell, the next wave of great artists would dare to cut against the prevailing tone of cynicism and irony, risking “sentimentality,” “ovecredulity” and “softness.”

Wallace called for art that redeems rather than simply ridicules, but he didn’t look widely enough. Mostly, he fixed his gaze within a limited tradition of white, male novelists. Indeed, no matter how cynical and nihilistic the times, we have always had artists who make work that invokes meaning, hope and mystery. But they might not have been the heirs to Thomas Pynchon or Don Delillo. So, to be more nuanced about what’s at stake: In the present moment, where does art rise above ironic ridicule and aspire to greatness, in terms of challenging convention and elevating the human spirit? Where does art build on the best of human creation and also open possibilities for the future? What does inspired art-making look like?

In the visual arts, an analogous form to recursive irony emerged with non-painting. Magnus Plessen had been the most adept innovator of the style. Four years ago, his work included paintings such as “Ladder,” which was composed of a largely white canvas and an image of a ladder created using blue and brown tape. The few brushstrokes that had been applied were scraped away by a palette knife. His thoughtful pictures of vapidity and antipainting permeated the painting culture until every MFA program included a painter using tape as decoration rather than tool. But instead of resting on the motif and style of a new convention, he now makes paintings that describe creation rather than destruction. His recent work is, dare I say, beautiful. Magnus Plessen moves against the reductive provisional trend he helped create by making increasingly intricate paintings of richer color, form and complexity. His 2013 painting, also titled “Ladder,” is now a top-to-bottom color spectacular of blues, blacks, yellows and purples. Now, the only areas of white are the ladder, rather than vice versa. Feet and hands are now rendered with a sensitive touch rather than being wiped away. He has turned from tiny steps toward nothingness and begun leaping toward eternity.

* * *

In the history of this country, no artistic tradition has done more to elevate the human spirit than black American music. If one wanted to write a book that advanced the novelistic tradition and the possibilities for humankind, one could learn something critical from studying, for example, “Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen.”

The opening words:

Nobody knows the trouble I’ve seen

Nobody knows my sorrow

Nobody knows the trouble I’ve seen

Glory Hallelujah

In an interview with Bill Moyers, Professor James Cone of Union Theological Seminary explains the seeming contradiction between the grief of the refrain and the promise of the closing exaltation.

And you sort of say, sure, nobody knows the trouble I’ve seen. Nobody knows my sorrow. Sure, there is slavery. Sure, there is lynching, segregation. But, Glory Hallelujah. Now, the Glory Hallelujah is the fact that there is a humanity and a spirit nobody can kill.

One can hear that abiding spirit in the voice of Sam Cooke in his pop adaptation of the song, and in renditions by others like Louis Armstrong and Marian Anderson. Cornel West elaborates on the contradiction between the refrain and rejoinder.

Glory Hallelujah is a tragicomic moment. Going to struggle anyway. Cut against the grain anyway. Never view oneself as a spectator but always a participant. Never view oneself as somehow outside the struggle but always meshed in it.

Both West and Wallace call for participation over spectatorship. We must move toward the Glory Hallelujah, toward the possibility of something greater. The best art can inspire us and push us closer.

One attribute of a move toward something greater is to reject the safety of ironic remove and risk the possibility of failure. In the mid-2000s, an acclaimed novel was published nearly annually that heralded a turn toward meaning-making, sincerity and redemption. Interestingly, each of the following novels had a few critical detractors who cried “sentimentality,” which goes to show the risk was taken. Marilynne Robinson’s "Gilead" (2004) is a novel of letters written from a dying pastor to his 7-year-old son. The old pastor’s reflections are mixed with anxiety and loneliness, but most of all, a deeply-felt reverence for the richness of everyday life. He revels in the beauty of two friends laughing, sunlight on a child’s hair and two kids “dancing around in [their] iridescent little downpour, whooping and stomping as sane people ought to do when they encounter a thing so miraculous as water.” He finds forgiveness and gratitude in the present, overcoming the grief of unresolved feelings and the pain of troubled relationships. In Mary Gaitskill’s "Veronica" (2005), the narrator Alison is an ex-fashion model sorting through bits of her life and friendship with Veronica, who died of AIDS. Alison’s memories arrive as powerful feelings that bring meaning to her present life as a middle-aged office-cleaner with hepatitis C. Her friendship with Veronica is a locus from which self-reckoning and release arises. Lastly, it doesn’t get much bleaker than the post-apocalyptic world of "The Road" (2006). Cormac McCarthy chronicles a father and son attempting to survive among desperados in the ashen ruins of modern society. They travel toward the rumor of a human community. When the father dies, the hope for this possibility lives on in the son, who continues their journey on faith. From reverence, to reckoning, to redemption, these three novels mark a larger shift in tone from the ironic to the sincere.

Skeptics reject sincerity because they worry blind belief can lead to such evils as the Ku Klux Klan and Nazism. They think strong conviction implies vulnerability to emotional rhetoric and lack of critical awareness. But the goal of great art is the same whether one approaches it seriously or dubiously. To make something new, to transcend, one must have an honest relationship with what is: history, context, form, tradition, oneself. Dishonesty is the biggest obstacle to making original, great art. Dishonesty undermines a work’s internal integrity — the only standard by which a work can succeed. If the work becomes a vehicle for one’s ego, personal or political agenda, self-image, desire for fame, adulation, fortune — human as these inclinations may be — the work will be limited accordingly. Even a desire to affirm human dignity and elevate the human spirit can be corrupted by dishonesty in the form of sentimentality. For James Baldwin, Harriet Beecher Stowe’s "Uncle Tom’s Cabin" serves as a prime example. Baldwin writes:

Sentimentality, the ostentatious parading of excessive and spurious emotion, is the mark of dishonesty, the inability to feel; the wet eyes of the sentimentalist betray his aversion to experience, his fear of life, his arid heart; and it is always, therefore, the signal of secret and violent inhumanity, the mask of cruelty.

Great art must be achieved through the integrity of its own internal principles. Irony alone has no principles and no inherent purpose beyond mockery and destruction. The best examples of irony artfully expose lies, yet irony in itself has no aspiration to honesty, or anything else for that matter.

So, where does art rise above ironic ridicule and aspire to greatness, in terms of challenging convention and elevating the human spirit? Where does Glory Hallelujah meet integrity?

* * *

Every two years, the Whitney Museum of American Art celebrates the best and brightest American artists in an exhibition known as the Whitney Biennial. For decades now, the exhibition has been showcasing work that results from relativism and ironic parodies of Western art history (See Dan Colen). However, the latest Biennial includes more than just banal cynicism and retro restyling. It rebuffs “everything goes” regionalism and pluralism. Instead, irrefutable achievement is celebrated. For example, Amy Sillman and Dan Walsh continually bring their paintings to a higher level through relentless rigor and introspection. Take for instance the color used by these two great painters. Rather than resting on a trendy palette of black, white, fluorescents and metallics, Sillman makes paintings, such as 2010’s “Drawer,” that invoke inspiration from innumerable greens and purples. She uses color to demonstrate new ideas rather than remind us of what’s stylish. Likewise, Dan Walsh has spent years willing brilliant articulations of color onto canvas. “Grotto” (2010) weaves together brush marks of brown and yellow. Colors that could be viscerally off-putting become a seductive tapestry. Both Sillman and Walsh execute painting with a desire to make history rather than capitalize on it. Their work depicts the human experience of toil and triumph through paintings that can be described all at once as lame, beautiful, emotional and thoughtful. And, if there was any question the Biennial is extolling sincerity, the exhibition also includes David Foster Wallace.

Audre Lorde riffs on Shelley’s poet legislator line:

[Poetry] forms the quality of the light within which we predicate our hopes and dreams toward survival and change, first made into language, then into idea, then into more tangible action… The farthest horizons of our hopes and fears are cobbled by our poems, carved from the rock experiences of our daily lives.

For Lorde, poetry is the practical means by which we sustain ourselves and chart a new world. Artists must take responsibility for finding the form to make our dreams real. They must assess a work as honestly as possible, seeking integrity. At one time, irony served to challenge the establishment; now it is the establishment. The art of irony has turned into ironic art. Irony for irony’s sake. A smart aleck making bomb noises in front of a city in ruins. But irony without a purpose enables cynicism. It stops at disavowal and destruction, fearing strong conviction is a mark of simplicity and delusion. But we can remake the world. In poetry, in music, in painting, we can reimagine and plot coordinates into the unknown. We can take an honest look, rework and try again. The work will tell us if it has arrived or not. We have to listen closely. What do we see? What do we hear?

Matt Ashby lives and writes in Greenfield, Mass. Brendan Carroll is a painter based in Atlanta. His most recent show was reviewed in April's edition of Modern Painters.

Shares