In the autumn of 1977, a film crew transformed the working-class West Berlin neighborhood of Wedding into the Warsaw Ghetto. Government officials in Poland and the Soviet Union had refused to give the production company permits to shoot in either country. The city did double duty as the capital of the German Reich and as occupied Poland. Although the German authorities allowed the movie studio to film there, the reception in Berlin was anything but universally positive. Swastikas were painted onto cameras, and rolls of film disappeared. One passerby was so angry about the Hollywood production that he threw bottles at the set. An old man screamed, “I killed you Jews once before. I’ll kill you again.”

The cast and crew persisted. After the blockbuster success of the miniseries "Roots" on ABC, about an African slave and his descendants, executives at rival NBC wanted their own miniseries, one with the emotional resonance of slavery. They chose the Holocaust. The director, Marvin J. Chomsky, had been one of the directors of "Roots" and was a television veteran, with episodes of "Star Trek," "Gunsmoke," "Mission: Impossible" and "Hawaii Five-O"among his credits. The novelist Gerald Green, author of "The Last Angry Man," was given the difficult task of squeezing the fates of millions of Jews into one identifiable and sympathetic group, the Weiss family.

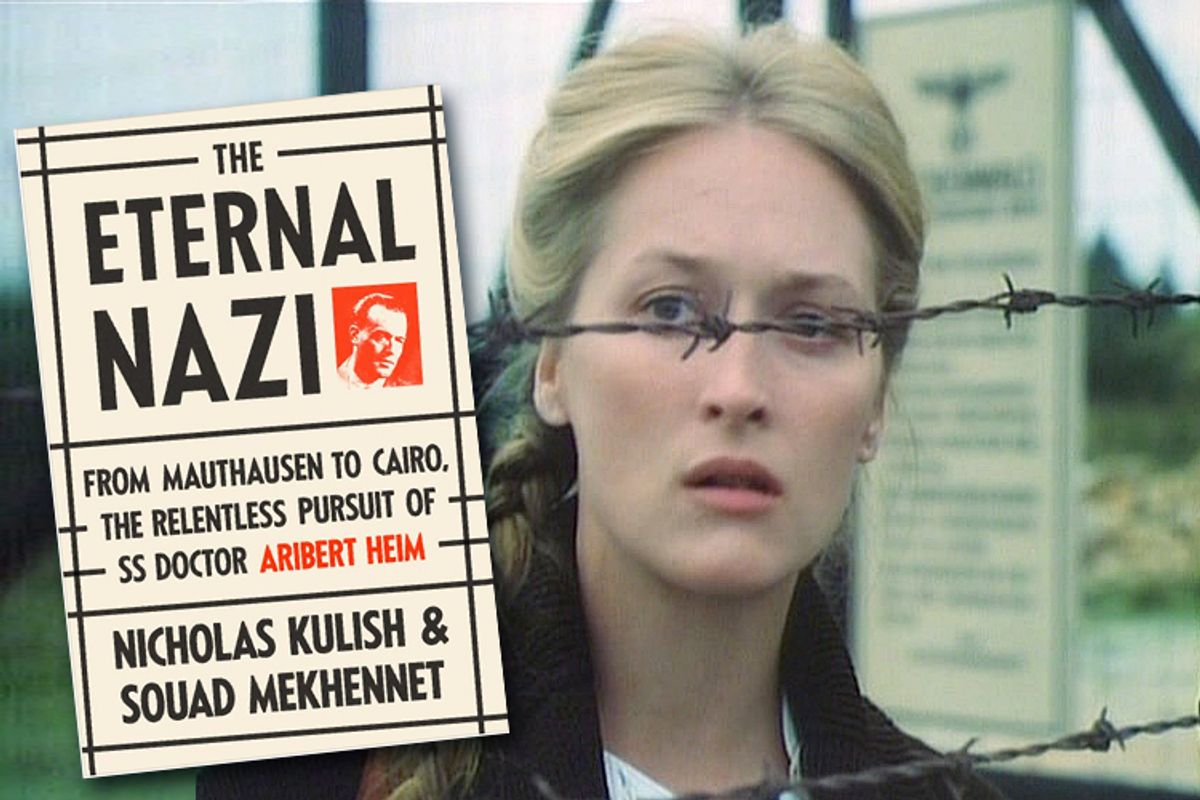

A single ambitious SS officer, Erik Dorf, played by the actor Michael Moriarty, later of "Law & Order" fame would serve as the primary carrier of German guilt. James Woods and Meryl Streep also starred in the miniseries as a recently married couple who would face unimaginable trials. Few would have predicted at the time that a mainstream entertainment aimed at an American audience would have a significant and lasting effect on Germany’s attitude toward its war crimes. The result was an unlikely national catharsis that would lead to greater public support for the pursuit of war criminals decades after the war. Far from flagging with the passage of time, investigations into Nazis were pursued with new vigor and growing resources. This continues today.

*

As The New York Times reported on the front page this week, prosecutors from what is known as the “grandchildren’s generation” are still hard at work trying to win convictions of death camp guards. Now they are using three-dimensional virtual models of camps to help juries visualize what they would have witnessed. They have access to the kinds of computerized databases that were not available to their predecessors. The other thing that was missing for the first German Nazi hunters was probably the most important element: popular support.

Today Germany is studded with plaques and bristling with statues in honor of the victims of the Holocaust but its people were not always so quick to accept or even discuss the war crimes and genocide committed by the Nazi regime. One of the main reasons they are hunting Nazis nearly 70 years after the war is that neither the Allies nor the Germans themselves did enough in the postwar years.

After the war, many German citizens, struggling with deprivation and occupation, blamed the upper echelon of the Nazi leadership for their own suffering at the end of the war and were happy to see them brought to account. Others grumbled about victors’ justice, a complaint that would grow with each new trial. Many Germans equated the civilians killed in Allied bombing raids over Hamburg and Dresden with the massacres in the east. The German people might have tolerated seeing Nazi leadership in the dock, but they wanted their privates, sergeants and lieutenants home, whether they served in the Wehrmacht or the Waffen-SS.

In the meantime the desire to hunt down war criminals quickly faded on the Allied side. The soldiers who had witnessed the gruesome scenes of death at the liberated concentration camps rotated back home. The famous Nazi hunter Simon Wiesenthal, who spent his early days tracking down perpetrators alongside the Americans, felt a distinct lack of drive among many of the U.S. officers. There were a few anti-Semitic comments that rang in the Holocaust survivor’s ears, making it that much harder to deal with the growing apathy on the part of his associates.

The focus of American enmity was rapidly shifting away from the defeated Nazis and toward the Soviets and Joseph Stalin’s rising ambitions in Europe.

The year 1947 was a fateful one for Germany. Talks had completely broken down between the Western Allies and the Soviets. Within two years, Germany was divided into two states, the German Democratic Republic in the east and the Federal Republic of Germany in the west. In his first government address in September 1949, the newly elected chancellor of West Germany, Konrad Adenauer, spoke for much of the nation when he declared, “Those truly guilty of the crimes committed during the National Socialist period and in war should be punished with all severity.”

The term “truly guilty” implicitly limited the circle of perpetrators worthy of prosecution. The pressure to discontinue the hunt for Nazi perpetrators continued to mount. That same year a group of lawyers founded the Heidelberger Juristenkreis, a lobbying and legal aid group for detainees and convicted war criminals. Even in the Soviet sector realpolitik calculations and desire to win over the Germans under their control brought the Russian search for Nazi war criminals to a halt. After convicting some seventy thousand prisoners of war, the Soviets declared an end to their own Nazi trials on September 14, 1950.

For a silent majority in Germany there was not so much support for Nazi sentiments as a desire to move on. Although many Germans were in favor of holding the most senior Nazi leadership accountable, they also believed the thousands of Wehrmacht soldiers still held captive in Siberia needed to come home. Leading politicians argued that the remaining detainees in the hands of the Americans, British, and French should also be released.

The German attitude was to ignore and rebuild and they managed to do so with stunning alacrity. The 1950s became known for what is called the Wirtschaftswunder or economic miracle. A few tough prosecutors pushed cases, like the Ulm trials of Einsatzgruppen members in 1958 and the Auschwitz trials in Frankfurt a few years later. A team was created to hunt down Nazi war criminals later that same year.

The enormity of the task—often compared to Hercules cleansing the Augean Stables—became clearer the deeper they delved, discovering, for instance, that the Gestapo had issued false identity papers to its officers in the spring of 1945. Building cases was an uphill battle in an uncooperative and at times obstructive justice system. Officials were as likely to warn former comrades of an imminent arrest as to help them arrest the accused.

Police officers regularly asked how they could stand to betray their own. The investigators were called “Nestbeschmutzer,” literally ones who soiled their own nests, but in spirit more like those who denigrate their country. They were cursed to their faces. Taxi drivers often refused fares to their headquarters, so they had to give nearby addresses in order to be picked up. “As a result of these hostilities,” one of the investigators, Alfred Aedtner, would later write, “more than a few asked to be relieved from the special commission. They were replaced with others for whom it did not go any differently.”

Aedtner described how he once appeared at the Stuttgart apartment of a police commander who had overseen the murder of more than ten thousand Jews, Communists, and partisans in the region around Minsk when he was a member of Police Battalion 322 during the war. The man’s wife loudly cursed Aedtner and his colleagues, saying the impending arrest was “worse than Gestapo methods.” She told him that it was beneath her husband to be arrested by such “little people.”

*

At the time of filming, Meryl Streep was a young Yale drama graduate, better known for her work on Broadway. It would be a little over a year before she received the first of her 18 Academy Award nominations for her supporting performance in the Vietnam movie "The Deer Hunter." James Woods was also still starting out, with half a dozen films under his belt.

Nazis were go-to villains in the 1970s for the entertainment business, with hit movies and books like "The Boys From Brazil," "The Odessa File" and "Marathon Man." Miniseries were a big deal in those days too, a precursor of the short-run, big-budget series now associated with HBO or AMC. But in the age of "Game of Thrones" and "True Detective" those old miniseries from the ’70s can look rather chintzy. When it aired on U.S. television in 1978, "Holocaust" generated significant controversy.

The author and survivor Elie Wiesel called the miniseries “untrue, offensive, cheap,” and “an insult to those who perished and to those who survived.” Particularly galling for many was the juxtaposition of genocide with bright and gaudy commercials for household products, which many deemed indecent, if not downright obscene.

The Holocaust miniseries aspired to be something more than a thriller about Nazi doctors in the jungle or a plot to start a Fourth Reich. This was miniseries as history. Many prominent voices said it fell far short. Writing in the New York Times, the television critic John J. O’Connor attacked what he called the “sterile collection of wooden characters and ridiculous coincidences” necessary to submit a single family to the events of Kristallnacht, the terrors of Auschwitz’s selection ramp, the Warsaw Ghetto uprising, and more. The miniseries was middlebrow entertainment, a sort of Holocaust “Forrest Gump,” at the infamous massacres of Babi Yar instead of fishing on a shrimp boat on the bayou.

Yet for all the criticisms, the miniseries was a professional production with star actors that brought the history of the Holocaust into millions of homes. German public television purchased the foreign rights in Germany for $600,000. The fact that it was state-owned television meant that the decision was politically charged from the start, urged by leading members of the left-leaning Social Democrats and largely opposed by the right-wing Christian Democrats.

“‘Holocaust’ puts the horror within boundaries, presents it in the same familiar limiting format as Westerns and murder mysteries, all of which we view as entertainment and something not quite real, not quite the truth,” said Helmut Oeller, the program director of Bavarian television, Bayerischer Rundfunk, who was against the broadcast.

Public critiques of the program’s commercialism, the soap-opera quality of its filming, and the historical inaccuracies led the directors of the main television network, ARD, to demote the miniseries to its regional stations. Expectations for the program were low and falling. Germans, it was widely believed, were tired of hearing about a war more than three decades in the past, tired of lectures about their culpability. The strange foreign word “Holocaust,” taken from the Greek holos and kaustos, for “completely” and “burned,” was almost unknown in Germany.

“The problem will be getting people to turn on their sets when it is broadcast,” said Heinz Galinski, leader of the Jewish Community of Berlin, with whom Wiesenthal had corresponded on the Heim case.

But not everyone, it turned out, was feeling apathetic about the renewed attention to the murder of the European Jews. Right-wing groups opposed to the broadcast were in some instances ready to take action to prevent "Holocaust" from airing. At 8:40 p.m. on a Thursday evening in January 1979, a ten-kilogram bomb detonated near Koblenz, severing television cables belonging to the regional public television station. Barely twenty minutes later another explosion destroyed the cables running from an antenna not far from Münster. A right-wing radical group claimed responsibility, saying its goal had been to prevent the airing of a documentary called "The Final Solution" in the run-up to the broadcast of "Holocaust." Weeks before the miniseries was scheduled to air, threatening phone calls to German television stations had begun.

The concerns of anti-Semites and unreconstructed Nazis were well-founded. When the four-part, seven-and-a-half-hour miniseries finally aired in Germany, viewers tuned in by the droves, with more than twenty million West Germans watching. One station, Westdeutscher Rundfunk, hosted “Midnight Discussions” after each episode, and roughly thirty-five thousand Germans called in. Viewing groups were started for singles because the program was considered too traumatic to watch alone. Nearly two-thirds of those surveyed by West German television and the Federal Office for Political Education described themselves as “deeply shaken.” After the broadcast the Holocaust turned into an inescapable national debate in Germany, on the front page of every newspaper, the cover of every magazine, discussed from elementary schools to universities, which would soon register a surge of interest in studying the crimes of the Nazi era.

Many things contributed to the change in attitudes. It was an evolution, from the hard, thankless work of the early investigators to the ’68 generation’s rejection of the mores and morals of the older generation. From Eichmann’s trial onward a series of events had chipped away at the German psyche, but the miniseries had a significant, measurable effect.

The Bundestag in Bonn was due to debate the statute of limitations for Nazi war crimes. A survey of twenty-eight hundred people before the program aired found only 15 percent of Germans wanted the statute of limitations rescinded. Two weeks later that figure had leaped to 39 percent. A majority of Germans, 51 percent, said before the miniseries aired that Nazi trials should end. After the program was broadcast, the number dropped to 35 percent.

“In the house of the hangman,” Der Spiegel wrote, “the rope was spoken of as never before.”

Meryl Streep played a key role in this national reckoning. Unlike most of the actors who portrayed either Jews or Nazis she was the Good German. Streep was blonde and angelic, loyal and true, dedicated in her love for her Jewish artist husband. A viewer could embrace the idea that the country was guilty while maintaining a notion of individual purity. The problem of collective versus individual guilt in some ways persists to this day.

*

No freedom for killers,” chanted the protesters dressed in concentration camp uniforms. They barged into the Bundestag chamber and disrupted the already-charged debate over the statute of limitations for Nazi war crimes. The window for prosecutions in cases of murder had been extended for four years in 1965 and for ten years in 1969. To many conservatives it was time to say enough. But Hans-Jochen Vogel, Germany’s justice minister, worried that war criminals might return from hiding the moment the statute expired.

At Wiesenthal’s insistence the Jewish Documentation Center in New York had printed up thousands of postcards with a picture of a German soldier shooting a woman with a baby in her arms. “This must never come under the statute of limitations,” the postcard read in German, English, and French. The postcards were sent to Chancellor Helmut Schmidt of Germany.

The awareness that Nazi war criminals were going unpunished had grown in the United States. On March 28, 1979, the U.S. congresswoman Elizabeth Holtzman of New York announced that the Justice Department was launching the Office of Special Investigations with a budget of $2.3 million to uncover and deport Nazi fugitives in the United States.

“There should be absolutely no question that the Department of Justice and the U.S. government will act unequivocally and vigorously to deny sanctuary in the United States to persons who committed the worst crimes in the history of humanity,” Holtzman said.

Six months after "Holocaust" aired, lawmakers in Bonn gathered to vote on the statute of limitations. A no vote would likely have served as a symbolic close to the pursuit of war criminals, even if fugitives like concentration camp doctors Josef Mengele and Aribert Heim could still have been prosecuted, because criminal charges against them had already been filed. But new prosecutions would not have been possible the next year if the vote had failed. On July 3, the Bundestag voted to suspend the statute of limitations for capital crimes by a narrow vote of 255 to 222, in no small part thanks to a schlocky American miniseries and a talented young actress named Meryl Streep.

From the book "THE ETERNAL NAZI" by Nicholas Kulish and Souad Mekhennet. Copyright © 2014 by Nicholas Kulish and Souad Mekhennet. Published by arrangement with Doubleday, an imprint of The Knopf Doubleday Group, a division of Random House Inc. All rights reserved.

Shares