Welcome to the wide world, Class of 2014. You have by now noticed the tremendous consignment of debt that the authorities at your college have spent the last four years loading on your shoulders. It may interest you to know that the average student-loan borrower among you is now $33,000 in debt, the largest of any graduating class ever. According to a new study by the Pew Research Center, carrying that kind of debt will have certain predictable effects. It will impede your ability to accumulate wealth, for example. You will also borrow more for other things than people without debt, and naturally you will find your debt level growing, not shrinking, as the years pass.

As you probably know, neither your parents nor your grandparents were required to take on this kind of burden in order to go to college. Neither are the people of your own generation in France and Germany and Argentina and Mexico.

But in our country, as your commencement speaker will no doubt tell you, the universities are “excellent.” They are “world-class.” Indeed, they are all that stands between us and economic defeat by the savagely competitive peoples of Europe and Asia. So a word of thanks is in order, Class of 2014: By borrowing those colossal amounts and turning the proceeds over to the people who run our higher ed system, you have done your part to maintain American exceptionalism, to keep our competitive advantage alive.

Here’s a question I bet you won’t hear broached on the commencement stage: Why must college be so expensive? The obvious answer, which I’m sure has been suggested to you a thousand times, is because college is so good. A 2014 Cadillac costs more than did a 1980 Cadillac, adjusting for inflation, because it is a better car. And because you paid attention in economics class, you know the same thing must be true of education. When tuition goes up and up every year, far outpacing inflation, this indicates that the quality of education in this country is also, constantly, going up and up. You know that the only way education can cost more is if it is worth more.

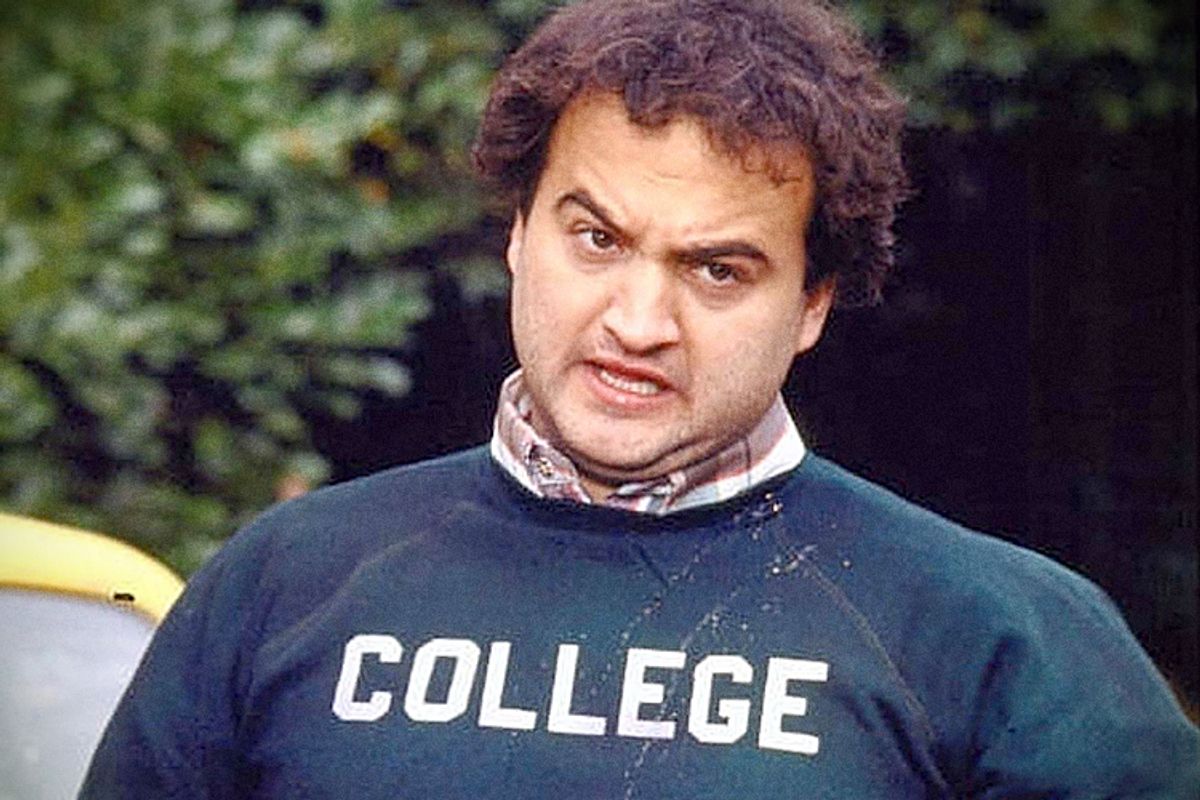

In sum, you paid nearly sixty grand a year to attend some place with a classy WASP name and ivy growing on its fake medieval walls. You paid for the best, and now you are the best, an honorary classy WASP entitled to all the privileges of the club. That education your parents got, even if it was at the same school as yours, cost them far less and was thus not as good as yours. That’s the way progress works, right?

Actually, the opposite is closer to the truth: college costs more and more even as it gets objectively worse and worse. Yes, I know, universities today offer luxuries unimaginable in the 1960s: fine gymnasiums, gourmet dining halls, disturbing architecture. But when it comes to generating and communicating knowledge—the essential business of higher ed—they are, almost all of them, in a frantic race to the bottom.

According to the Delphi Project on the Changing Faculty, only about 30 percent of the teachers at American colleges these days are tenured or tenure-track, which means that fewer than a third of your profs actually enjoy the security and benefits and intellectual freedom that we associate with the academic lifestyle. In 1969, traditional professors like these made up almost 80 percent of the American faculty. Today, however, it is part-time workers without any kind of job security who are the majority of the instructors on campus, and in general these adjuncts are paid poorly and receive few benefits. That is who does the work of knowledge-transmission at the ever-so costly, ever-so excellent American university: Freelancers. Contract laborers.

The awful lives of these workers is the subject of a vast and popular literature. Read around and you will discover that these adjuncts sometimes collect food stamps and live out of cars, that they race from job to job, that they inflate grades and endure whining rich kids and come to despise the academics they once sought to join. The most shocking tale of all (so far) concerned an 83-year-old adjunct at a university in Pittsburgh who was reduced almost to the level of a homeless person before dying last year from an illness that she endured without benefit of health insurance from her employer.

What makes all these stories so irresistible, of course, is their overwhelming sense of irony. These adjuncts are people who once believed they were signing up for a life of teaching, writing and highbrow contemplation. And just look at the world of shit they got instead. Many of them have PhDs and many work hard at teaching. But it seems that all the learning in the world, all the good grades and high test scores—which they had too, remember, just like you—don’t mean a goddamned thing when people have no bargaining power.

Yes, you are a screwed generation, Class of 2014, with a helping of debt that will take you many years to digest. But consider this other generation that has also been screwed, and screwed by the very same people who secured that millstone to your neck. You borrowed and forked over enormous sums in exchange for the privilege of hearing lectures . . . lectures that were then delivered by people who earned barely enough to stay alive. It is a double disaster of the kind that only we Americans are capable of pulling off.

Actually, it’s worse than that. This is a disaster not only for individual adjuncts but for the production of knowledge itself. What do we really expect college classes to be like when they are taught by people in such dire situations? Is our new precarious professoriate able to research or write at the same pace as its predecessor? How many of them feel secure enough in their position to defy the prevailing conventions of their disciplines?

“No major new works of social theory have emerged in the United States in the last thirty years,” wrote the anthropologist David Graeber in an important 2012 essay about this age of diminishing innovation. “We have been reduced to the equivalent of medieval scholastics, writing endless annotations of French theory from the seventies. . . .” I emailed Graeber and asked him to elaborate. Here’s what he said:

“If you look at the lives and personalities of almost any of the Great Thinkers currently lionized in the American academy, certainly anyone like Deleuze, or Foucault, Wittgenstein, Freud, Einstein, or even Max Weber, none of them would have lasted ten minutes in our current system. These were some seriously odd people. They probably would never have finished grad school, and if they somehow did discipline themselves to appear sufficiently “professional,” “collegial,” conformist and compliant to make it through adjunct hell or pre-tenure, it would be at the expense of leaving them incapable of producing any of the works for which they have become famous.”

It is not easy to discover how heavily any one school uses adjuncts, because the data depends on voluntary disclosures by the institutions themselves and because the number of adjuncts reported doesn’t tell us how many classes those adjuncts teach or how much time they spend on campus. Still, numbers do exist for some institutions, thanks to a survey done by the Department of Education. What you’ll find: some of the most expensive universities in America are also big employers of part-time, non-tenure-track labor. Remarking on this situation, a spunky website for the college-bound asks, “There’s No Other Way to Put It: They Like Adjuncts. What’re You Gonna Do?”

It’s a good question. What are you gonna do? The obvious answer, for adjuncts themselves, is to organize, and they are doing it all over the country. The rest of us need to ponder how to stop this insane situation from getting any worse. We might begin by understanding college less as a mystical place of romance and achievement and more as a cartel or a predator, only a couple of removes from a company like Enron or a pharmaceutical firm that charges sick people $1,000 per pill. We might ask why the numbers of university administrators have grown by some 369 percent since 1976, why college presidents are sometimes paid over a million dollars a year, and why state legislatures keep cutting education budgets and passing the burden along to students and their parents.

The word we always hear in connection to university price increases is “unsustainable.” The price tag of college can’t keep going up forever. But of course it can, and the party that will “sustain” it, just as soon as you get those loans paid off, will be you.

Shares