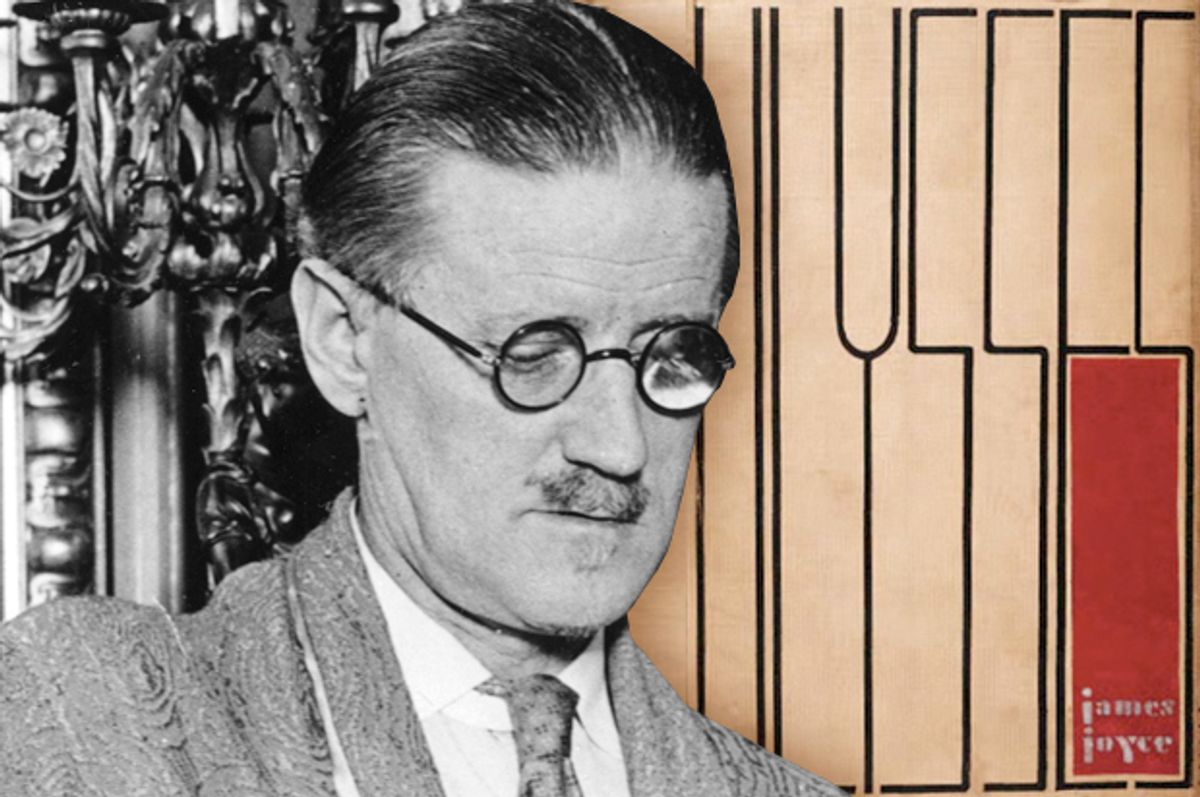

James Joyce's "Ulysses" changed literature and the world, not necessarily in the ways its author intended and certainly in ways we still don't entirely understand. One of the unexpected effects of the novel, which was first published in its entirety in Paris in 1922, was the most famous obscenity trial in U.S. history, conducted in 1933. That trial serves as the culmination of Kevin Birmingham's astute and gorgeously written "The Most Dangerous Book: The Battle for James Joyce's 'Ulysses,'" an account of the tortuous path Joyce's masterpiece took to print. Publishing is not the world's most fast-paced and high-stakes business, but when it came to introducing the English-speaking world to a novel that one critic deplored as "full of the filthiest blasphemies" and "afflicted with a truly diabolical lack of talent," the ride was a wild one.

Countless reams of paper have been consumed by writings on Joyce and "Ulysses," but Birmingham has two particular, little-discussed themes to bring to the table. First, and most peripheral to his narrative, is Birmingham's discovery of strong evidence that the eye problems that tormented and eventually blinded Joyce were caused by syphilis. (Birmingham concludes that a medication given to Joyce by his Parisian doctor in the late 1920s was probably "an obscure French drug called galyl," used only to treat symptoms of syphilis.) Birmingham expands on this a bit by arguing that the effects of pain and disability on the writer and his work have been underestimated. It's a credible argument, especially once you've read this book's squirm-inducing description of a typical eye surgery Joyce endured and learn that he went through the equivalent a dozen times over. But Birmingham never quite gets around to showing how Joyce's suffering shaped his work.

More central to the story is Birmingham's interest in the role women played in midwifing "Ulysses." There's the novel's muse -- Joyce's wife, Nora Barnacle, who could never be bothered to read the thing -- and his longtime patron, a genteel Englishwoman named Harriet Weaver, who published excerpts from the novel in her literary magazine as well as funneling the impecunious author cash amounting to $1 million in today's money. In the U.S., the two editors who first risked prison and fines to publish portions of "Ulysses" in their journal, the Little Review, were Margaret Anderson and Jane Heap. Then there was the bookseller Sylvia Beach, who, as her inaugural venture in publishing, produced the first full edition of the notorious novel despite the seemingly endless (and expensive) revisions Joyce insisted on making to the text, even after it had gone to proofs. When the Little Review was brought up on obscenity charges for publishing Joyce, female supporters filled the courthouse, and when a New York City bookstore needed middlemen to receive copies of "Ulysses" smuggled in from Paris, the volunteers were all women.

Birmingham underlines the irony in this: The obscenity laws that banned the novel in America and England were supposedly meant to "protect the delicate sensibilities of female readers." The first major push against the Little Review in the early 1920s was initiated by a businessman who discovered a copy of the magazine among his teenage daughter's possessions and freaked out after reading the section of "Ulysses" Joyce called "Nausicca." (It features a young girl named Gertie MacDowell displaying her legs to protagonist Leopold Bloom at the beach. The businessman's daughter claimed she never bought the magazine and that it had simply appeared in the mail one day. Sure.) This protective outrage represented a holdover from 19th-century notions of novels (especially French novels) as dangerous reading for young girls. How easily their impressionable minds could be filled with dreams of passionate love and their moral fiber loosened! It was not men like Bloom the censors feared would be inflamed by books like "Ulysses," but girls like Gertie MacDowell.

When "Ulysses" finally got a serious hearing a decade later -- thanks to the efforts of Bennett Cerf and his upstart publishing company, Random House, along with civil liberties attorney Morris Ernst -- one of the issues at hand was the definition of obscenity. It had long been viewed as consisting of any material that might "corrupt" a pure and impressionable mind. Many of the people trying to maintain the ban on "Ulysses," such as the assistant U.S. district attorney assigned to the case, Sam Coleman, acknowledged that it was not pornography; Coleman called the novel a "literary masterpiece." But under earlier understandings of obscenity, this hardly mattered. Justices were not even expected to take the whole work into consideration. If innocent women and children could be tainted by exposure to its raciest passages, then the work was illegal in the U.S.

United States v. One Book Called Ulysses overturned that conception of obscenity forever. Judge John M. Woolsey found that while the novel contained "many words usually considered dirty, I have not found anything that I consider to be dirt for dirt's sake." Furthermore, he told Ernst, "Ulysses" included "passages of moving literary beauty, passages of worth and power." The two elements are inextricable. As Birmingham puts it, Woolsey asserted that "the novel was transcendent, that it turned filth into art." That is, in fact, the point of it.

"The renovation of 'Ulysses' from literary dynamite to a 'modern classic' is a microhistory of the way modernism was Americanized," Birmingham writes. He's particularly adept at briskly and vividly sketching the way Joyce's literary project epitomized the modernist ethos. The novel "demanded unfettered freedom of artistic form, style and content -- literary freedoms that were as deeply political as any speech protected by the First Amendment." But what Joyce wanted to do with that freedom was not to preach political revolution but to speak with complete and comprehensive honesty about everyday and intimate experience. In "Ulysses," relatively straightforward accounts of the events in a single day in the lives of two Dubliners, Bloom and Stephen Dedalus, run counterpoint to their fragmented and cascading thoughts and fantasies -- the stream of consciousness. Birmingham writes, wonderfully, that "Ulysses" "split the ego" presented in Joyce's early novel, "A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man," into two characters "and that split is the fission through which the world pours out."

Because of the truth Joyce wanted to tell, "Ulysses" contains some of the most ravishing and profound passages in the English language and it is also pretty dirty. That made it not only one of the greatest novels ever written but the perfect book to overthrow the existing definitions of obscenity. "Ulysses," with the power of its language and vision, defied collective decorum to crack open the allowable and permit a new literature to emerge. Birmingham conveys the excitement of this insurrection with great skill, knitting together the story of Joyce's vexed personal life with those of the various characters who recognized and championed his genius even as they were often at each other's throats. (A smashing movie could be made about the interactions among Anderson, Heap, Ezra Pound and John Quinn, a finance attorney and art collector who funded the Little Review and seemed equally attracted and disgusted by the lesbian bohemianism of its two editors.)

One lasting legacy of "Ulysses" can be observed in the ubiquity of another Random House title, freely available in bookstores everywhere today although it would most definitely have been deemed obscene in 1933: E.L. James' "Fifty Shades of Grey." It turned out that the American public's resistance to "dirt for dirt's sake" was a lot less robust than its resistance to stream-of-consciousness narratives. "After 'Ulysses,' modernist experimentation was no longer marginal. It was essential," Birmingham writes. That's debatable, as is Birmingham's belief that there's a necessary link between the desire for sexually explicit art and "the larger struggle between state power and individual freedom." Nevertheless, the two have coincided at certain pivotal historical moments, and never more gloriously than in the battle for "Ulysses." It's a story that, as Birmingham puts it, forced the world to "recognize that beauty is deeper than pleasure and that art is larger than beauty." He has done it justice.

Shares