Eleven-score and 18 years ago, our forefathers brought forth on this continent – OK, they weren’t our actual forefathers, in most cases – a new nation, conceived in liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal. It’s been a mixed bag, to say the least. Ever since, we’ve had trouble figuring out what that word “liberty” is supposed to mean, in the American context. And even if we set aside the use of “men” as a 19th-century convention, the proposition that all of them are created equal was a gigantic rhetorical dodge, even in Abe Lincoln’s day. Women and enslaved African-Americans and Native Americans driven off their lands and white men of all classes stand equal and naked before the Lord, in other words, but not before the law or anywhere else this side of heaven.

It’s Fourth of July weekend in the second decade of the 21st century, and our backyard cookouts, beach getaways and fireworks displays are somehow meant to symbolize our fealty to the ideals of the American Revolution. As we are now dimly and uncomfortably aware, that globe-rattling 18th-century event was shot through with hypocrisy and contradiction. It’s difficult to feel any national unity when we can’t agree on what ideals we’re talking about, which version of the revolutionary narrative we like best or exactly why it was worth bothering about. Were the Founding Fathers building a Christian nation or a monument to Enlightenment reason? (In either case, they papered over some big problems.) Do we prefer the soaring democratic rhetoric of noted slave-rapist Thomas Jefferson, or the pragmatic cynicism of proto-Wall Streeter Alexander Hamilton?

As I wrote last year after a visit to the living-history park at Colonial Williamsburg, no one amid a crowd of hundreds had any answer for the actor playing infamous turncoat Benedict Arnold, when he rode into Virginia’s colonial capital at the head of a Redcoat regiment. (That actually happened, in 1781.) You losers threw away British security over a few pennies in taxes, Arnold scoffed – what was that all about? There was some mumbling and booing among the masses. “Religious freedom!” someone shouted. “We’re taxed too much!” said someone else. Tithe to the Church of England and you may worship as you please, Arnold retorted. And your taxes under the Continental Congress are many times higher than the Crown ever dreamed of imposing. No one said much after that; you got the feeling people knew there must be a bigger answer than God and taxes, but they couldn’t come up with it.

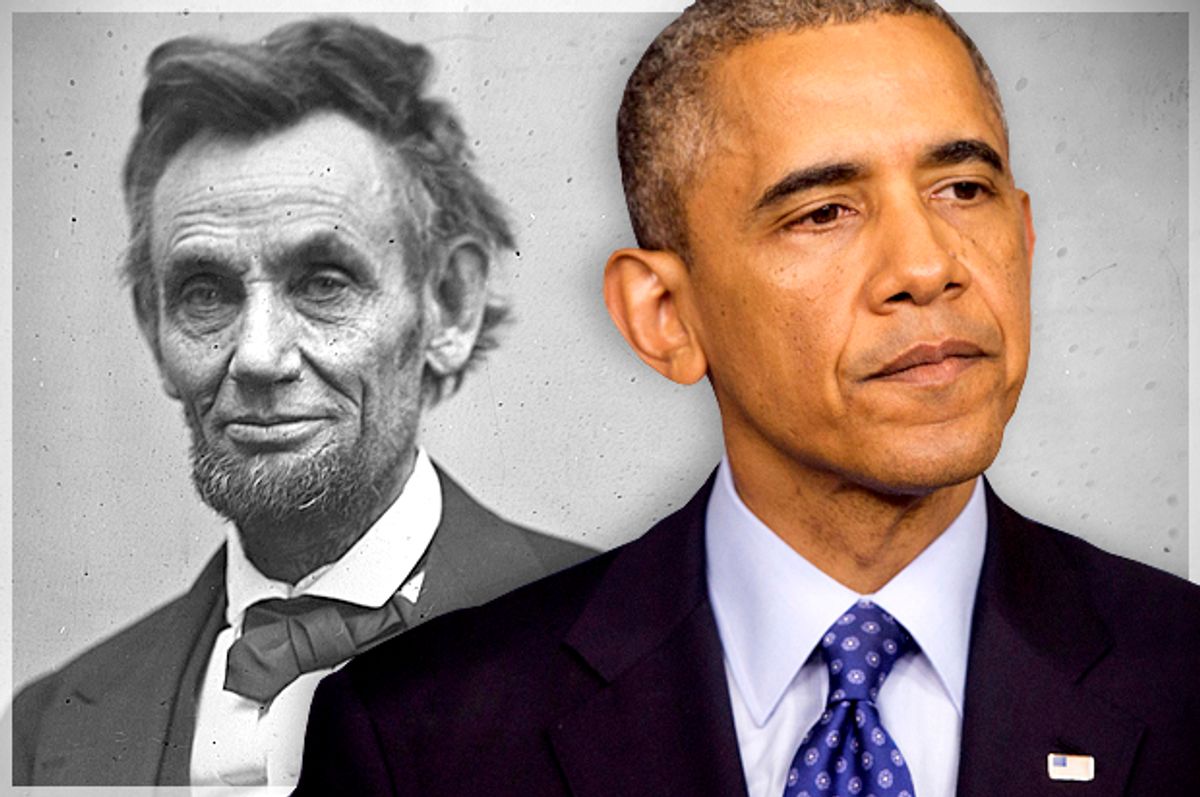

Political and cultural divisions go back to the birth of our republic, and well before that: Colonial Williamsburg vividly conveys the sense that even in open rebellion Virginia considered itself English, in a way Massachusetts did not. (That Anglocentric historical sense colors the character of the Old Dominion to this day.) We’ve certainly had periods of political paralysis and intractable conflict before; Lincoln’s greatest speech, the one I misquoted above, came at the climax of one such episode. He was, of course, trying to build a sense of unity and shared national identity out of the chaos of the Civil War and the shameful compromises of the decades before that. In effect, Lincoln argued that American history up to that point had been a faulty prelude or a dress rehearsal for the real thing. Consecrated by the “honored dead” of Gettysburg, the nation would have “a new birth of freedom,” and those highfalutin Fourth of July phrases in the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence – so flowery compared to Lincoln’s blunt, brief address – would finally start to mean what they said.

I don’t need to recite the succeeding 150 years of tumultuous American history to convince you that it wasn’t quite that simple – not for women, not for African-Americans, not for Native Americans and not for the generations of immigrants who were only beginning to become part of the American fabric. Not for anybody, really. But Lincoln’s genius lay precisely in the fact that he saw the American republic as a work in progress, and did not delude himself that redeeming its promise could happen overnight. His words were and remain seductive and prophetic, not least because he speaks to our desire for narrative fulfillment, our BBQ-flavored, Fourth of July yearning to believe that the American enterprise has a sacred purpose and was not fatally undermined by its initial clusterfuck of compromises.

I’m aware of the attitude I’m supposed to hold in order to be a decent 21st-century liberal, which is that America is crawling in its imperfect fashion toward the realization of Lincoln’s vision of liberty and equality. There are absolutely things to celebrate on our national holiday, even if they come with asterisks. Racism and sexism linger on, but old-school open discrimination is broadly illegal. Gay people can get married in more and more places (soon nationwide, no doubt), and the helpless apoplexy of Rick Santorum and Antonin Scalia at that fact is pleasant to contemplate. Blow a doobie on the streets of Seattle or Denver, and the beat cop will wish you good morning. (That particular struggle for liberty will take longer to go nationwide, for peculiar political reasons.) We elected a black president, who couldn’t have anointed himself as Lincoln’s heir or the fulfillment of his prophecy any more obviously.

To paraphrase Martin Luther King, Jr., who was himself paraphrasing the 19th-century Unitarian minister Theodore Parker, we are to take comfort in the idea that the arc of the moral universe has a long-ass bend, but one we can see slowly bending toward justice. I’m not much of a good American liberal, as it happens – personally and professionally, I’m the guy who’s always going to tell you the glass is slightly less than half-full – but I believe that too. I’m less convinced that the United States of America is the divine instrument of that long arc, or that our country will be around to see it touch down one blessed day, or whether that even matters.

This is hardly breaking news, but the cultural and political divisions of Lincoln’s day are still with us, in subtly altered form, while the sense of national unity he meant to be his legacy long ago dissipated. It’s a truism to say that the Civil War never really ended, but that doesn’t make it untrue. That unresolved conflict looms up in our rear-view mirror like an onrushing tractor-trailer out of Quentin Tarantino’s nightmares, emblazoned with the Rebel flag and loaded with the Confederate undead. If we want to hoist a PBR or four to the social-justice victories of the last several years on this Fourth of July, well and good. But let’s also recognize that the country we see around us is pretty close to ungovernable, and that Barack Obama’s quest to become the Lincoln of his time – the Great Unifier 2.0 – has already failed.

When I started thinking about a holiday-weekend column, it occurred to me that almost everything I have written since I started doing weekly political commentaries, and almost everything my fellow columnists at Salon write, boils down to observations on the ungovernable nature of America. Consider just the past few days: Michael Lind wrote a persuasive essay about how the bipartisan political system (never mentioned in the Constitution) marginalizes all kinds of nonconformist or dissenting opinions, including but not limited to libertarians, Tea Partyers, anarchists and socialists. That system’s supposed intention is to enable middle-ground compromise, but in the current context it produces overheated rhetorical warfare and total legislative paralysis in Washington (often over meaningless technical matters) while enabling an elite bipartisan consensus on all kinds of big stuff that the public largely hates, like the care and feeding of Wall Street bankers, our disastrous foreign policy and the secret national-security apparatus.

Freelancer Paul Rosenberg chipped in with a speculative piece about how the religious right, feeling itself losing power in the country and even within the Republican Party, now longs to join forces with neo-Confederate wingnuts who dream of an all-Christian, all-white secessionist republic carved out of the Deep South or the Great Plains. I actually think the prospect of armed Christian insurrection is something of a liberal bugaboo, but Christian soldiers are waging war on numerous other fronts. As Katie McDonough and Elias Isquith have reported all week long, the Supreme Court’s 5-4 decision in the Hobby Lobby case suggests how much the Roberts Court has become a sock-puppet for religious extremists and corporations, legislating from the bench and awarding those interests with victories they couldn’t win through the normal political process.

The subtext of all these stories – and for that matter, of the piece I wrote a few weeks ago about the demise of democracy – is that the most powerful and affluent nation the world has ever seen is now eating its own internal organs, in political terms, and none of us has the slightest idea what to do about it. One can make sense of the current state of the conflict, tactically and strategically: Yes, the internal forces of social justice have won some important victories, mainly on LGBT rights. But the forces of retrograde amnesia, of big money and white male hierarchy and Bible-pounding superstition, have counterattacked vigorously in areas where they think they have the upper hand, including reproductive rights and climate science and unlimited corporate power. As the rest of us have finally noticed, on those fronts that side is winning one glorious victory after another.

You can’t blame Obama for not being Abe Lincoln, especially when there are so many other things to blame him for. He wanted to be a president of unity and reconciliation, one who renewed our national sense of purpose and aimed it at something or other, maybe climate change or inequality. But his defeated opponents did not want to unify or reconcile with him about anything, so he hasn't done any of that stuff. Obama may have been reminded of the lesson Malcolm X preached some decades ago: It’s no good believing in the brotherhood of man if other men don’t want to be your brothers.

There’s certainly no other politician on the national stage capable of bringing our endless civil war to an end – not Hillary Clinton, not Jeb Bush, not Ted Cruz, not anybody. (Do I take malicious glee in the prospect of a 2016 Clinton-Cruz showdown, the all-time horror-show of American presidential elections? No. That would be wrong.) But Obama may find himself in the unfortunate historical role of James Buchanan rather than Lincoln, meaning the hapless dude who tries to patch the widening cracks in the dam and leaves office just before it gives way.

Am I forecasting some near-term implosion of the American nation-state, which even in its debilitated condition remains the world’s biggest military superpower as well as the principal host organism for global capitalism? I guess not; that would be a wildly incautious prediction, relying on numerous implausible things all happening at once. I am saying that the public is getting sick of the anti-democratic game of Freeze Tag in Washington, in which Republicans and Democrats take turns being “in charge” and doing nothing, and that it isn’t sustainable into the indefinite future. Let's also observe that if someone had told you in 1983, at the height of Reaganite Cold War hysteria, that the Soviet Union would be history in less than a decade, well, that person would have sounded nuts. Now go get those chicken wings and ice down some brews. And remember: You read it here first.

Shares