It is said that in 16th-century Prague, a giant made of clay stalked the slums from moonrise till sunbreak. He kept a vigil, this earthen colossus, and guarded the Jews of the ghettos in an era of pogroms. By nightfall in Prague, when the townsfolk kept inside, heeding their curfew, marauders slinked along the streets to heave bricks through windows and scrawl obscenities on lintels.

In 1580, a rabbi arose who promised a manmade messiah. Judah Loew, a mystic called the Maharal, whispered spells and commands into a clod of mud and sculpted a monster to crush the vandals and brutes. A clockwork man, a witless machine, the sentinel followed the rabbi’s orders to the letter: “Clear the precinct after dusk.” The creation meted out justice with alarming aplomb, splitting skulls and snapping femurs. Blood dappled the cobblestone lanes, and soon the oppressors avoided the ghettos altogether. Enjoying a safe season, the Jews roamed their neighborhood freely after dark. Yet the golem had not forgotten his instructions — empty the streets — and turned on his people for lack of other targets. For seven nights in a row, until the rabbi reversed his magic, the giant ran amok. The golem had become a goliath, plucking heads and limbs from the torsos of innocents.

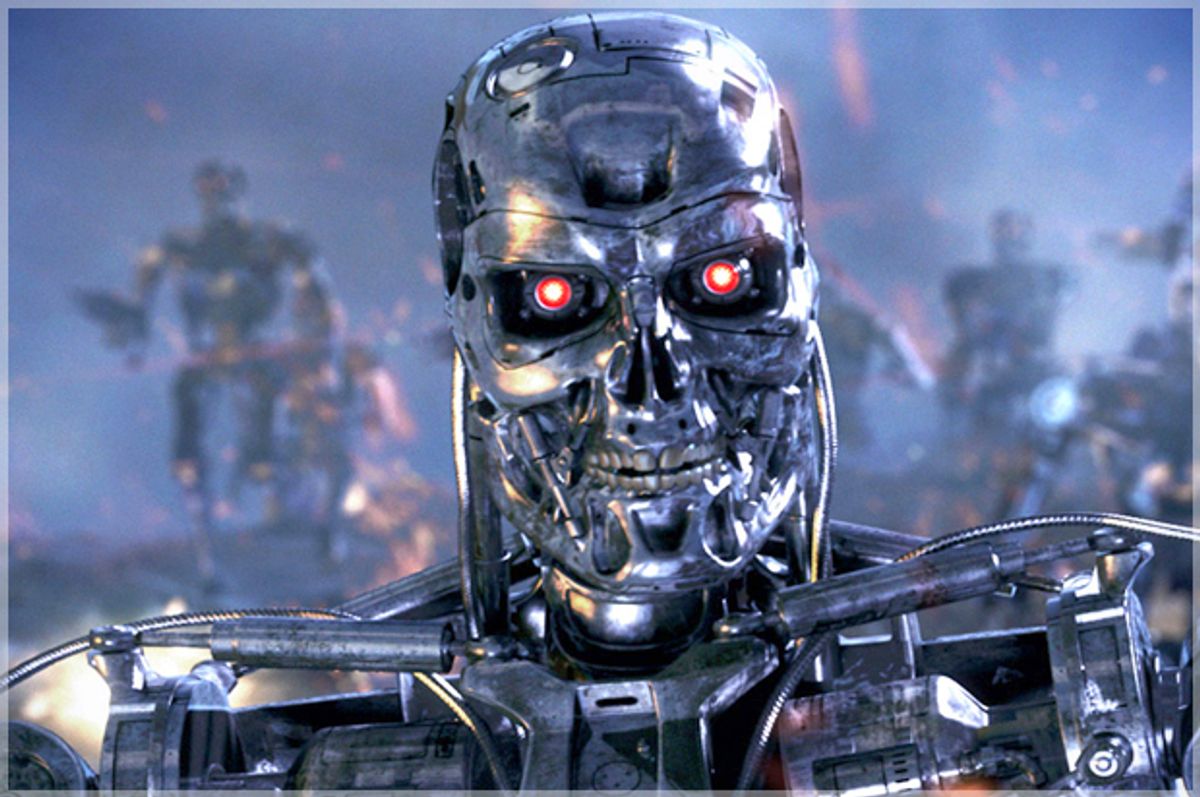

Fairytales are for campfire powwows and bedside reveries. Their bugbears seldom intrude on the political realm. Yet the golem isn’t mere nursery chatter. The likeness of this beast, the archetypal war machine, is alive and well in the here and now. While the Czech maintain that he lies sleeping in the attic of a Prague synagogue, they are mistaken. The golem, if you can stomach the comparison, resides in the United States. He resides there and in Russia and South Korea. Today he is built not from clay and spells but toothed gears and pneumatic pistons. He has machine guns for arms and infrared cameras for eyes. These nations are churning him out on an assembly line, powered by the wheels of war. Soon his kin may watch the streets of a hundred thousand Pragues, their sidearms smoking incessantly over mountains of brass shells.

The United Nations has its own name for our latter-day golems: “lethal autonomous robotics.” In a four-day conference convened on May 13 in Geneva, it described them as the imminent future of conflict, advising an international ban. “Lethal autonomous robotics (LARS) are weapon systems that, once activated, can select and engage targets without further human intervention,” the council said in a report released before the session. The UN called for “national moratoria” on the “testing, production, assembly, transfer, acquisition, deployment and use” of sentient robots in the havoc of strife.

The ban cannot come soon enough. In the American military, Predator drones rain Hellfire missiles on so-called "enemy combatants" after stalking them from afar in the sky. These avian androids do not yet cast the final judgment — that honor goes to a lackey with a joystick, 8,000 miles away — but it may be only a matter of years before they murder with free rein. Our restraint in this case is a question of limited nerve, not limited technology.

Russia has given rifles to true automatons, which can slaughter at their own discretion. This is the pet project of Sergei Shoygu, Russia’s minister of defense. Sentry robots saddled with heavy artillery now patrol ballistic-missile bases, searching for people in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Samsung, meanwhile, has lined the Korean DMZ with SGR-A1s, unmanned robots that can shoot to shreds any North Korean spy, or doe-eyed refugee, in a fraction of a second.

Some hail these bloodless fighters as the start of a more humane history of war. Slaves to a program, robots cannot commit crimes of passion. Despite the odd short circuit, metal legionnaires are immune to the madness often aroused in battle. The optimists say that androids would refrain from torching villages and using children for clay pigeons. These fighters would not perform wanton rape and slash the bellies of the expecting, unless it were part of the program.

Yet the program would have inherent vices, and these are the pivot points of the scare.

On pages and projection screens, dystopian fabulists envision a world where android slaves revolt, re-gifting their manacles to their human masters. Sheer fantasy, that future. Such thoughts plague only bug-eyed conspiracists in dark basements and comic-book fiends in extended adolescence. Even so, no myth wants entirely for truth. The truth here is more mundane but equally unacceptable.

“’Autonomous’ needs to be distinguished from ‘automatic’ or ‘automated,’” the UN report observes. “Automatic systems, such as household appliances, operate within a structured and predictable environment,” while “autonomous systems can function in an open environment, under unstructured and dynamic circumstances.” The embattled android would make its own decisions in the fickle, murky, feverish arena of war. Given the shifting ethical complexities of every second in the killing fields, the judgment and deeds of a robot would be utterly unpredictable and inveterately inadequate.

By the UN’s reckoning, combat calls for “human judgment, common sense, appreciation of the larger picture, understanding of the intentions behind people’s actions, and understanding of values and anticipation of the direction in which events are unfolding.” A poverty of context would afflict these iron shooters, inuring them to matters of insight and mercy. Imagine a coward girding himself in a human shield, and tell me whether the war machine would pause or let the napalm drench them both like rain. The walking Gatling gun would be equally ill-equipped to make the most standard distinctions required by international law. When pitted against all the learning disabilities known to modern neurology, the binary brain often fails in sub-simian ways, and the electric gunman would find it hard to sort active combatants from civilians, let alone soldiers about to surrender.

Along with the inevitable crimes against humanity would come an excuse for strategists intending to perpetrate them. “A responsibility vacuum would emerge,” the UN forewarns. The horrors of war recuse themselves in bureaucracy. In her monograph, "On Violence," the philosopher Hannah Arendt notes that “in a fully developed bureaucracy, there is nobody left with whom one can argue, to whom one could present grievances, on whom the pressures of power could be exerted.” A war waged by an army of androids, outfitted with weapons but not will, would offer the ultimate gift of bureaucracy: total unaccountability. An automaton cannot answer for its actions. After torching a hut of huddled women and children, no robot would hear its Miranda rights and monologize in front of a jury. All violence would become anonymous in this faceless infantry, and the powers would write off all evils as errors. For military leaders, rampant murder would devolve to mere negligence.

Even as naïfs tout a lessening in the loss of life, even as they say that shattered machines would be better than soldiers brought home in boxes, death on the opposite side would swell to unprecedented proportions. A robot army would reduce the human risk of invasion, trimming the threshold to war. “Modern technology allows increasing distance to be put between weapons users and the lethal force they project,” the UN report avers. With our smart bombs and Predator drones, we can — and do — already waste villages by pressing red buttons from the comfort of recliners in Fort Drum and Langley. A commander should sink his nose into the stink of war, into its pong of burning flesh, smoking gunpowder and evacuated bowels. Kept from the nausea of butchery, an aggressor can kill without even meaning it. Victims become mere tallies in spreadsheets, signs of some vague progress. The UN notes that robots “would add a new dimension to this distancing, in that targeting decisions could be taken by the robots themselves. In addition to being physically removed from the kinetic action, humans would also become more detached from decisions to kill — and their execution.” Besides numbing us to what it means for others to suffer in war, our bandoliered androids would help us forget what it means for us to suffer in war. The cost of conflict would be purely economic, a chance of busted springs and fried wires. Skirmishes abroad would become noncommittal, capricious and arbitrary, opening the gate to perpetual carnage.

The wayward automaton is a time-honored fear, going back as far as ancient Greece. Daedalus was famed for the hubris of fitting his son, Icarus, with waxen wings that melted in the sun, but he was equally well known for tinkering with “living statues,” or androids. In Plato’s "Meno," Socrates tells Callistratus that “you have not observed with attention the images of Daedalus. If they are not fastened up, they play truant and run away.” Yet even Daedalus shied from rigging his toys with the tools of homicide. Millennia later, that danger is real and present, and in May 2014, a host of Nobel Peace laureates released a letter demanding a ban. “Billions of dollars are already being spent to research new systems for the air, land, and sea that one day would make drones seem as quaint as the Motel T Ford does today,” the notice reads, signed by Archbishop Desmond Tutu, former President F. W. de Klerk of South Africa, former President Lech Walesa of Poland, and many others. (Notably absent was the recipient of the 2009 Nobel Peace Prize, President Barack Obama.) “It is unconscionable that human beings are expanding research and development of lethal machines that would be able to kill people without human intervention,” the signatories say.

These robots are our golems — utterly unpredictable, entirely unaccountable, alarmingly enabling. The horizon of war reeks of their casualties, with every blue face, every lank arm, the output of an arbitrary machine. It is said that in sixteenth-century Prague the rabbi Judah Loew felled his golem once and for all by scribbling met, the Hebrew word for dead, on its head. Let us retire our golems before they inscribe the same word on ours.

Shares