At first, they died in the bullring, but the book that made them famous had swelled the crowds. By mid-century, the lack of space made it harder to outrun the bulls, so they began to die much earlier in the route, beyond Hotel La Perla, and most just before the bulls made their 90-degree turn onto Calle Estafeta.

I was there in Pamplona, standing on the balcony of the piso near this precarious juncture. It was 8 a.m.; the stone streets were shiny with rain. There was a wood barricade, like an outfield wall, that unnaturally ended Calle Mercaderes and forced the route right onto Estafeta. This is where I saw the first bulls slip, losing their footing at the turn, their bulk hitting the stones, their tonnage pounding into the barricade, the runners fleeing to the sidewalks, some, in fetal curls, waiting for death.

This was how the last American was killed in Pamplona, along this narrow corridor that offers no escape from the charging bulls. That morning, his killer, “Castellano,” had begun to run the 826 meters from the Cuesta de Santo Domingo to the Plaza de Toros at an unusually torrid pace, which frightened the runners and sent them scurrying. One of them fell.

Castellano plunged his horns into the limp American on the ground, goring his stomach and piercing through to his aortic vein. He began to crawl. But there were still more bulls in the stampede, and by the time the Red Cross unit got to Matthew Tassio, most of the blood had already drained from his body. He was dead just eight minutes after he finally reached the hospital.

Tassio's was the 14th death in the recorded history of San Fermín -- the festival most famous for hosting the annual "Running of the Bulls" -- and the last American to die there. One other has perished since, in 2003, and many others have been badly damaged by the bulls, but perhaps none have died as gruesomely as the American did in 1995. I wasn't in attendance for that run, thankfully.

In a year in which there would be no deaths, I came to Pamplona for the second time by bus from Madrid, passing through the sunflowers of Basque country. I had been invited by the correspondents of the Associated Press, with whom Dow Jones Newswire, my former employer, shared its local outpost to witness the Running of the Bulls from their prized perch.

That morning’s encierra would be the first of the new millennium. It was very wet and, even from the balcony, you could see the unevenness in the cobblestones. The only place to witness the run was from the balconies of the apartments along the route. When the bulls began to stampede, the runners, many still drunk and wearing all white save for a red pañuelico around their necks, filled all of the space in the corridors. It was a jogging gait until they saw the bulls. Most of them ran well ahead of the danger, but some were eventually chased down by the bulls.

I remember an American student who slipped nearly died on the curb by the cigarette shop on Estafeta, trampled, blood maroon in the grooves of the cobblestones, a small crowd coagulating around him to watch for death.

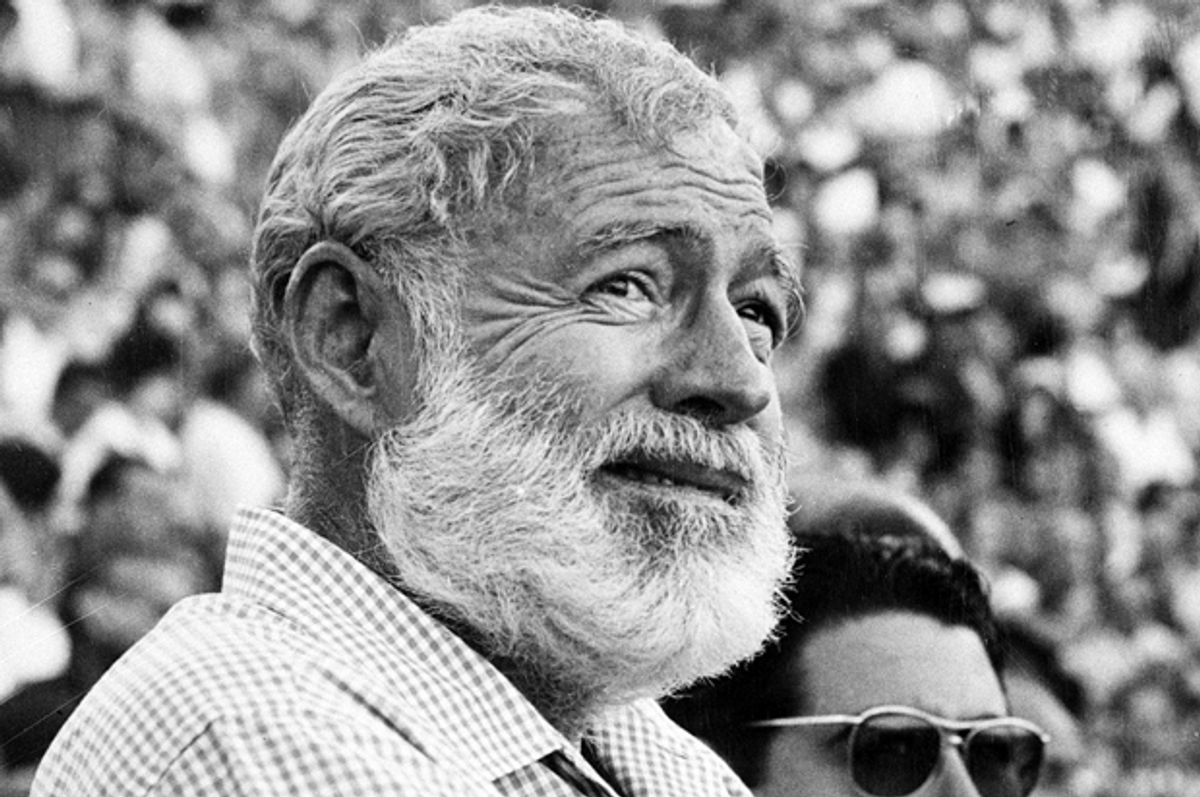

I remember the dense crowds, the public drunkenness, the street drink that kept you drunk and alert made from equal parts Coca-Cola and red wine. And, of course, I remember the monumental visage of Ernest Hemingway that hung down the side of the Hotel La Perla, where he set the novel that first recorded this mad dash from mortality.

* * *

It is not an overstatement to claim that Ernest Hemingway introduced Pamplona to the world. Until he first wrote about it in 1923 in an article for The Toronto Star Weekly, the San Fermín festival had been a regional affair: “As far as I know we were the only English speaking people in Pamplona during the Feria of last year,” writes Hemingway. “We landed at Pamplona at night. The streets were solid with people dancing. Music was pounding and throbbing. Fireworks were being set off from the big public square. All the carnivals I had ever seen paled down in comparison.”

This Toronto Star sketch of Pamplona comes from the appendix of new edition of “The Sun Also Rises,” released last week by Scribner’s to commemorate the 90th anniversary of its publication. The “updated” version will titillate Hemingway aficionados:

Drafted over six weeks across Spain (mostly in Valencia and Madrid) in the summer of 1925, set in Jazz Age Paris amid the psychic ruins of the Great War, "The Sun Also Rises" endures as one of the finest first novels ever written. Its itinerant narrative of Spain and France (they were largely unknowns to the American traveling public in 1925, but more on that later), depictions of café life and drinking, bullfighting and affairs with matadors, were all new to novels of the time. “No amount of analysis can convey the quality of 'The Sun Also Rises,’” went the original review of the book in The New York Times in 1926. “It is a truly gripping story, told in lean, hard, athletic narrative prose that puts more literary English to shame.”

Hemingway chose to evoke disillusionment through Jack Barnes, an expatriated American foreign correspondent living in Paris, and his married paramour, Lady Brett Ashley. Their romance is complicated, to say the least: Jake’s manhood was marred in the war and he cannot procreate (in his famous interview with The Paris Review in the 1950s, Hemingway was adamant that Jake was not a eunuch). The war injury was a crucial detail in the text, and an emblematic signature of the Hemingway code that ran through his subsequent work. His male characters bore physical or psychic wounds (sometimes both). Jake’s injury was an outward symptom of an interior crisis suffered in the wake of WWI.

Hemingway’s genius was present in Jake and Lady Brett as protagonists and antagonists. We inflict our own wounds, Hemingway seems to say, an insight that bears out even today: Contemporary disillusionment is concerned with the surprising, man-made ironies of modernity -- a dwindling sense of freedom, both existential and civil; the West's waning hegemony even amid unparalleled wealth and technology; a diminished middle class and shrinking American dream; and an ever present sense of looming doom (an attack of some kind, perhaps) by forces beyond our control. The Lost Generation time of “The Sun” was infected with its own disillusionment, owing to man-made origins from the tragic period of 1914–1918. This disillusion plays out in “The Sun” almost nihilistically; by the novel’s end, both characters are badly damaged by the preceding events, degraded, alienated.

* * *

The two opening chapters, cut by Hemingway but offered to readers in the new edition, were fortunate omissions. The original opening lines of “The Sun” sound an awkward, conversational, and Victorian tone, inconsistent with the remainder of the novel:

This is a story about a lady. Her name is Lady Ashley and when the story begins she is living in Paris and it is Spring. That should be a good setting for a romantic but highly moral story.

Yet, in the rest of the deleted chapter, and elsewhere in the early passages, the Hemingway voice is undeniably present. That voice has drawn veneration and ridicule. The essayist E.B. White, hardly the type for big-game hunting and encierros, penned a famous parody of Hemingway in The New Yorker in 1950, deriding his so-called declarative prose style. Yet much of Hemingway’s best writing strains this easy stereotype. He is far less aphoristic and quotable than, say, Don DeLillo (a veritable one-man factory of sound bites), and you would find it difficult to locate a pithy tweet among the prose of "The Sun Also Rises."

By the 1930s, Hemingway’s writing style had grown more intricate. “Green Hills of Africa” contains a buffalo of a sentence, 497 words spanning five pages, reminiscent of Faulkner or Gabriel García Márquez. That magical realist, in fact, had lionized Hemingway. Writing for the New York Times about a fleeting, chance encounter with Hemingway on Paris's Boulevard St. Michel, Márquez declares that “[Hemingway's] instantaneously inspired short stories are unassailable” and calls him “one of the most brilliant goldsmiths in the history of letters.”

For better or for worse, that unmistakably declarative, taut, gritty Hemingway music can overpower the substance of his stories, somewhat ironically drawing the attention back onto himself. Over the decades since his death in 1961, the Hemingway legend has bloomed and rebloomed many times over, until now there is a preoccupation with the Hemingway lifestyle, the man himself, in a way, morphing posthumously into a tourist destination, a literary Jimmy Buffet.

Those places in “The Sun” – Pamplona, Madrid, Paris – remain open for tourists, poet manqués, backpackers and the traveling gentility. But the tourism and concomitant commercialism have rendered quite a few of their landmarks ersatz. At the Closerie des Lilas in Paris’ Montparnasse district, where Hemingway set many scenes from his books (including my favorite, “A Moveable Feast”), practically the entire bar menu is a monument to Hemingway: daiquiris and mojitos, all made from Cuban rum, all named after Papa. After its much celebrated renovation, the Hotel Ritz saw fit to refurbish itself with a Hemingway-themed restaurant, L’Espadon ("The Swordfish"), in homage to Papa’s love of fishing, along with a Hemingway-inspired bar, which, no doubt, mixes up fanciful permutations of mojitos and daiquiris named after… you guessed it. The Spanish may have even more flagrantly exceeded the French in their quest to annex the Hemingway legend into their geography. Calle de Hemingway in Pamplona leads directly into the bullring. Placards outside restaurants on the Calle Cuchilleros in Madrid proclaim, rather declaratively, that “Hemingway ate here.” The website of Madrid staple Botin’s, the world’s oldest restaurant and where Hemingway set the final scene of “The Sun,” devotes cyber text to Papa, even directly quoting the final chapter.

A question worth considering: Were he alive today, could Hemingway have written a novel as great as “The Sun”? So much of its wonder derives from his keen eye for the undiscovered, heretofore unknown traditions. Ours, though, is a world of uber-awareness, search-engine omniscience. Those with wanderlust possess all manner of means to beam into a faraway place, efficiently and affordably, even instantaneously. One afternoon, in writing this essay, I called up Google Earth to view the squares and streets where I had been 14 years ago, astounded by the clarity of the street-level views. For the next few minutes, I flitted to and fro around the globe, a Peter Pan visiting Anthony Bourdain places.

* * *

I had first read “The Sun” in high school and was unaffected by it. Not until I had decided to move abroad after college and take up residence in Spain did I take up the text again. This time I clung to it, savoring every word about where to travel and where to eat and how to live like a good, knowledgeable expatriate.

Barcelona in July was a late-summer swamp. Soon, I missed the cool weather and took an overnight train north to the Basque country. In San Sebastian, I walked at dusk along the promenade that curled around the bay past the stalls that sold tiny, rare mollusks you picked like popcorn out of a cone of rolled newspaper. I saw some school kids perform the ancient Basque Riau-Riau dances and walked around the complicatedly arranged streets, names clotted with diphthongs, that smelled of the Atlantic, looking for Hemingway experiences.

That did not come until Pamplona.

It was late afternoon in August and very hot when I arrived. In my bag was a journal from my mother, some unremarkable reading, dirty clothes, a few measly legs left of a Eurorail pass I had purchased in Harvard Square the month before.

I had not thought the city would be so different after San Fermín, but I had come too late: the city was half-full. I roved for much of that afternoon, dodging in and out of curio shops and whatever else was open out of season. When it was dinnertime, I studied the menus of the restaurants off the Plaza Castillo until I found somewhere with a menu written only in Basque. I befriended a fellow traveler, Ryan, who was also from Massachusetts, and we made up plans to go drinking at a café in the Plaza Castillo afterwards.

By our third bottle of Estrella, an American couple approached to ask if they could join our table.

“We live in Paris and I am so tired of Paris that we have to leave. All I want to do is go back to Chicago but he won’t go,” she said.

“But Paris is so special,” I said. “Don’t you enjoy any part of it?”

“I despise it. They hate all Americans and you can smell the cheese in the cheese shops even from the street.”

She was menacingly beautiful and skeletal in that model way. Mark was a photographer, a little stout and balding, his shirt unbuttoned a touch salaciously. They had eloped some years ago and were living in an attic flat on the Île de St. Louis. When she began to flirt openly with Ryan, he would not look at her. When the couple began to quarrel, she kept saying she wished to return to America.

It was nearly midnight now and we were the only ones left in café in the colonnade of the plaza. Across the way, the lights were all out at the Hotel La Perla. There was only moonlight in the great square. When she finally began to kiss him, her husband placed his bottle on the table, stood, and shook his head at me. She was giggling the entire time.

Shares