Just before she picks up the phone for another interview about her latest album, the ambitious “I’m Not Bossy, I’m the Boss,” Sinéad O’Connor has a run-in with an Italian journalist who isn’t interested in her craft. “He said that if he could only talk to me about music, there wasn’t much to talk about,” she explains. “So he’d rather not bother talking at all.”

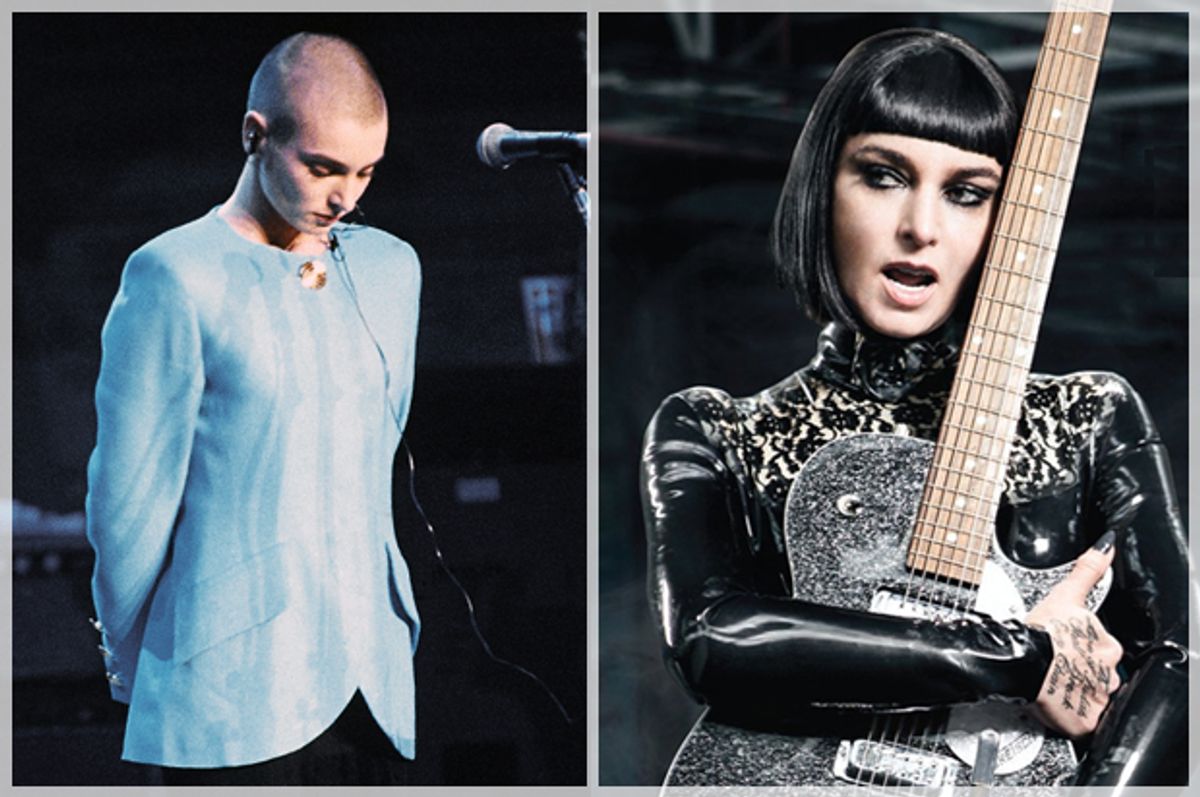

It’s the kind of comment the Irish singer-songwriter hears surprisingly often. She has courted controversy through her career, starting when she showed up on album covers and in videos with her head shaved bald. Journalists and even fans rarely let her forget that time back in 1992 when she ripped up a photo of the pope on “Saturday Night Live” or that time in 2013 when she penned an open letter to Miley Cyrus. For many listeners she is less a musician than a tabloid star.

That is, however, a grievous misperception. O’Connor is first and foremost an artist with a formidable voice, a gutsy interpretive style and a songwriting approach that changes with every album. Her 1988 debut, “The Lion & the Cobra,” was feisty and angry, full of snarling guitars and banshee howls. She wielded her scimitar voice mightily, yet showed a confident hand in songcraft. She followed it up with the quieter “I Do Not Want What I Haven’t Got” in 1990, mixing folk strums with programmed drums and landing a smash hit with a cover of Prince’s “Nothing Compares 2 U.” Rather than explore any one particular musical vein, she has experimented with big band, reggae and liturgical music, exhibiting the kind of range that generally earns male musicians endless praise.

O’Connor has refused to simply fade away, as so many ’90s singer-songwriters have done, and in 2012 she released the unlikely comeback album, “How About I Be Me (And You Be You)?” Her rawest and liveliest record in years, it paired searing songwriting with minimal backing, pushing her vocals to the forefront to remind listeners that she has one of the most unique instruments in pop music. Here was O’Connor reborn, a songwriter who had found some distance on her own troubles yet could still fearlesslty inhabit every note she sang. “I’m Not Bossy” builds on those triumphs, expanding her musical range with forays into psych-rock, love songs and one of the heaviest numbers she’s ever committed to tape (“Harbour”).

O’Connor spoke to Salon recently about her recent troubles in the music business, her new approach to songwriting, the rejuvenative power of the blues, and finally stepping up to be her own boss.

The album title “I’m Not Bossy, I’m the Boss” was inspired by the Ban Bossy campaign. What made you identify with that project?

In the music business, male and female artists are treated as if we are working for the people who are in fact working for us. I could be wrong, but I imagine it’s more exaggerated when you’re female. And I have had over the years great difficulty when it comes to being respected and even being acknowledged as the boss, so it can be very hard to get people to act on your instructions. I’ve called up various people who were working for me over the years and asked to see such and such a document, and I’ve been told that I really don’t need to see it. When you assert yourself as a female boss and put your foot down on important matters, you can be treated as if you’re just being difficult or bossy. People generally flounder for the nearest man that they can relate to as a boss.

Around the time the campaign kicked off, I was going through these issues and was having a hard time being heard on a particularly important matter. So I identified with the campaign from the point of view of being a female who has experienced over the years a certain amount of abuse for being assertive. I think Sheryl [Sandberg, the Ban Bossy founder] has hit on something very important. There is this attitude toward females. It does start when you’re a little girl, but it also exists when you’re a grown woman. It’s not okay to be assertive if you’re a woman. So I was just very inspired not only as a woman but as a boss. The campaign helped me exert a bit more control in my business and to feel safer about behaving like a boss.

The album was originally titled “The Vishnu Room,” but you changed it a few months before the release.

That was made possible by the fact that the record company wanted to change the cover. After we had done the cover shot, I thought, why don’t I get done up like a girl? We could do two or three shots to create some publicity for the album. That’s all that was supposed to happen with those shots, but when the record company saw them, they asked if they could put one on the cover. I said okay. Plus, it was a good opportunity to change the title. It was good luck all around.

The album has a strong narrative thread. It seems to tell the story of a woman dealing with strong desires and romantic betrayals. Were you writing toward a larger story, or is that how the songs came out?

I was deliberately writing toward something, so I’m really pleased to hear you say you noticed that. I used to write from a very different platform. I grew up in a very abusive situation, and I had a lot of shit to get off my chest. So I used to write a lot about me. It was all about my life. Once I got that all off my chest, I changed the platform from which I write, and I’m more inclined to use characters the way someone who writes books does. And they’re really characters on this album. I wanted to convey a narrative. It’s a romantic album; I wanted to write love songs, which I’d never done before. But I also wanted to illustrate the maturing of a female character. She matures from a romantic girl who puts the idea of romance on a pedestal into someone who understands the difference between love and romance. She learns that when you only have desire, that’s not safe. You have to have something else.

On “The Voice of My Doctor,” which is the sixth song on the album, there’s a very sudden shift in tone, where it goes from romantic to very raw and angry. How do you prepare to create that kind of performance?

The great thing is that you don’t prepare. I am what I call a Stanislavski method singer but I write the characters that I play. When you’re up on the stage or in the studio, you don’t really know what the character is going to do. You can’t plan for it as such. You have the words that are written on the page, but you don’t know how they’re going to come out or how that character is going to express herself through you. That’s what’s so fun about it. It’s your job to see what happens. You just have to get yourself out of the way.

Does that change the way you sing some of your older material? Do you see a younger version of yourself as a character to play?

The way I’ve been trained as a singer is a method called bel canto, where you don’t use notes or scales. You use the emotion of the characters. The rule of bel canto is that you don’t sing a song you can’t emotionally identify with. If as a method singer I cease to find anything inside myself that I can use in a song, then I don’t perform that song anymore. But that hasn’t happened very often. For example, I’ve been singing “Nothing Compares 2 U” for 25 years, and I’m always able to find something every night. I’ve grown beyond using my own experiences. Now I imagine I’m other people talking to other people. I know I sound mental, but that’s what I have to do. It will vary from night to night, but I usually have a plan in my head as to who I’m imagining I am and who I’m talking to.

Does that approach present difficulties when you’re working on an album and you can’t find the emotional hook for a particular song?

You would find it with new songs because they’re always exciting and fresh. If you came across a difficulty, it would be with older songs, which aren’t really character songs. I didn’t actually get around to writing character songs until that last album. Up until that point, all the songs I wrote were extremely autobiographical, so there was always something I could identify with. They might mean something slightly different to me now that I’ve matured a bit, but it’s still me. On my first album there are a couple of songs that I can’t do anymore. One is called “Drink Before the War” and the other is “Never Get Old.” I love those songs, but I wrote them when I was 15 and pissed off at my headmaster. I can’t identify with them anymore. Also, “Troy.” I don’t perform that song because I don’t feel that anger anymore. I can’t act it. I wrote those songs when I was a teenager and can’t identify with them at the age of 47.

When you made the switch from autobiographical to character-driven songwriting, was that freeing? Nerve-wracking? Both?

It was very exciting. It was quite a surprise. There are a lot of writers in my family — not of songs but of novels or stories. So in a way, I ought not be surprised. Once she had expressed everything that needed to be expressed, I put the suffering Sinéad O’Connor to bed. I guess I found what would have been there had the suffering not been there, which was really just a writer. It wasn’t a conscious decision. Characters just started to appear. It’s very freeing because you can write about stuff you could never write about otherwise. You can be someone else. That’s symbolized by the cover.

Writing this album, I was very influenced by blues. That’s really what’s at the heart of this album, even though it’s not a blues album. I spent the last two years listening to a lot of blues — not the sad kind, but the happy funky blues. Chicago blues. People like Magic Sam, Buddy Guy, Howlin’ Wolf, Elmore James, Guitar Slim, Sonny Boy Williamson and Freddy King. I listened to a lot of what they had to say about songwriting, too. They talked constantly about the facts of life — just saying things very simply. When you look at the blues catalog, it’s really about love and romance. I imbibed so much of that into myself that it changed how I wrote and how I wanted things to sound, and that’s why it’s a very guitar-driven album. Everything’s really short and sweet, with the odd exception.

What sparked that obsession?

After the last album I went on tour, and I had been put on a medication by the name of Tegretol. It’s for an illness that it appears I didn’t actually have, and I had a bad reaction to the medication. It makes you suicidal, unfortunately. When I discussed it with my health care provider and told him I was having difficulty with the medication, he didn’t realize I was having this reaction and doubled it. So the reaction was stronger and I had to leave the tour. I actually Googled whether or not this stupid medication could kill me, and I saw a warning box that said, if you’re having this reaction, get to a hospital. Within a day of me doing that, I was assailed by all manner of businesspeople who weren’t allowing me to recover. Financially speaking, everybody was trying to fuck me over. There was no consideration for the fact that I was unwell, and nobody was prepared to wait a few months before they tried to extort large amounts of money out of me. I had to find an accountant who discovered that over the years there had been all manner of stuff going on. It was all a bit depressing, and I thought, if I’m ever going to survive in the business of music, I need to fall more in love with music. Because otherwise I’m going to run.

A friend of mine, an Irish artist named Don Baker, is into blues and he said to me, this is a good time to start investigating blues. So I did, and I instantly fell in love. I’d been aware of blues before then, but I went on a journey. I became very interested in watching live performances on YouTube. I didn’t want to deal with the types of people I would have to deal with in order to stay in the business. It can be ugly — a very vampiric arena. But the blues were a great blessing. It’s all I listen to and all I watch before I go on stage. Howlin’ Wolf became my performing idol. In a way I think there has always been some male artist, like Bob Dylan or Van Morrison or Buddy Guy, who are musical godfathers to me, I suppose is the best way to put it. You can follow them along the road and they keep you alive as a musician.

How has that obsession with blues changed how you perform?

Even before that, I was all about live performance. But the business end of music had made me not want to perform live and not want to deal with music at all. But these guys made me realize that you can stay in music and not lose your soul. You can have fun playing music. That’s a really important thing to get back — the fun and the soul of it, making music for the sake of making music. It didn’t really change the way I perform, but it gave me enormous excitement to perform. I used to be very shy about performing. I was very self-deprecating in a lot of ways. I couldn’t understand why people liked me. I felt like an impostor. But these blues guys… you couldn’t watch them and not want to play like them. They really gave me back my joy in being a musician.

Shares