Look around the blogosphere, and there seems to be a serious crisis of conscience among feminists -- one that even predates Roxane Gay's trailblazing new book on the subject. One woman wonders: “I Love Wolf Whistles and Catcalls: Am I a Bad Feminist?” Another asks: “Am I a Bad Feminist Because Sometimes All I Want for My Life is to Get Married, Have Babies and a Nice House Out in the Country?” And: “Can a Beauty Editor Be a Feminist?” Everywhere you turn, there’s an overwrought unburdening by a woman wringing her virtual hands over the prospect of feminist failure — confiding her self-diagnosed Bad Feminism, unpacking its minutiae, and then ultimately concluding that, damn it, she’ll call herself a feminist if she wants to. Who says we can’t have it all?

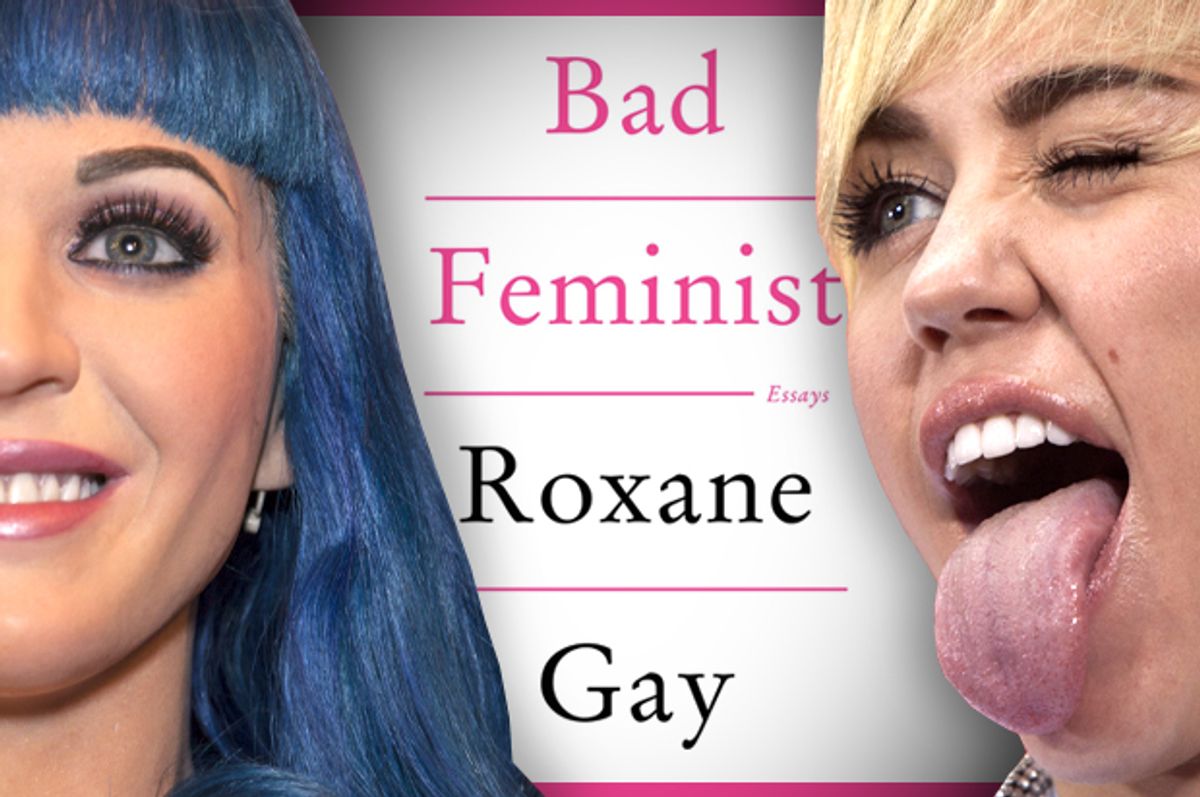

Perhaps it’s not surprising that people find themselves so easily tied in ideological knots over feminism, given that it still occupies such a contested place in American culture. Miley Cyrus rushes to proclaim that she’s “one of the biggest feminists in the world,” while Katy Perry and Shailene Woodley blithely disavow the term; meanwhile, right-wingers like Sarah Palin valiantly attempt to co-opt the term for uses the second wave never intended, and the consumer marketplace shills Dove products and Pantene shampoo with watered-down feminist rhetoric about self-acceptance and empowerment. Is it any wonder that many of us aren’t sure where and how the term is rightly applied?

“Choice” feminism started as the belief, coined somewhat peevishly by Linda Hirshman in her 2007 manifesto “Get to Work,” that a woman’s freedom to choose trumps her right to equality. But in the years since — and thanks to “Sex and the City’s ' Charlotte York, who in one memorable episode chanted “I choose my choice!” like a mantra — it’s devolved into the idea that anything is a feminist choice so long as a feminist chooses it: not just relationships and kids and career but also religion, sex work, dieting, breast implants, stiletto heels, gun ownership, capitalist megalomania. The morass of choice is at the heart of these most recent self-flagellating screeds. And the specter of being a “bad feminist” tends to crop up around the issues that have most confounded choice feminism: marriage, children, beauty standards and the attendant rituals surrounding all three. Debates around changing your name in marriage, for instance, are perennial headline-grabbers, with a staunch defense of both sides erupting periodically in mainstream newspapers and online. Likewise, strenuously argued “High heels are feminist!/No, they aren’t!” back-and-forths pop up as regularly as Anthony Weiner dong shots.

But in a world where we’re all choosing our choices, there seems to be a lot of second-guessing going on. At first, I likened these confessions to a parallel trend, that of the “bad mom” memoirs and essays that regularly circulate through the blogosphere and publishing world. But they’re not the same at all. The performativity of those, at least, has something of a rationale: It’s less about actually being a bad mom than it is about showing that you fancy yourself a cool, nonconformist mom. Trumpeting your feminist infractions, on the other hand: Sure, you’re being honest. But is it an honesty that anyone needs?

If this were a true revelation about acting against agreed-upon feminist goals, that would be one thing. An essay titled, I don’t know, “Am I a Bad Feminist Because I Picket My Local Planned Parenthood Every Weekend, Yelling ‘BABY KILLER!’ Repeatedly?”: That would be the work of a bad feminist. She’s actively working to curtail the bodily autonomy of other women. She gets to call herself a bad feminist, because she is. You, the Thought Catalog writer who dreams of being a stay-at-home mother with a country house? You’re just an oversharer.

I would hope that this goes without saying, but in case it doesn’t: None of these writers — the country-home coveter or the catcall fan or the beauty editor — are at risk of being drummed out of feminism, greeted at the clubhouse with a “GO HOME, TRAITOR, WE SAW YOU SMILE AT THAT DUDE WHO WHISTLED AT YOU” sign on the door. Because there is no official body. There is no clubhouse. Yes, there are a scant few people out there who have appointed themselves an unofficial feminist police force, patrolling Twitter and Op-Ed columns and jumping at every opportunity to point out how others are Doing Feminism Wrong. But these people are a tiny fraction of a multifaceted, increasingly inclusive movement. To make them the face of feminism is not only counterproductive but also disingenuous.

Much more often, the people these essays confess to fall into two camps. There are those of us who understand that life as a feminist unfolds as a series of small and large negotiations within a system (let’s call it “patriarchy”) that’s the only one we’ve ever known. It’s important to be honest about the ways that years and years living within this system has circumscribed women’s lives and labeled their choices and beings as valid and invalid, valuable and worthless, credible and crazy. And it’s just as important to acknowledge that everything from clothing to child-rearing to an appreciation of horror films comes with a series of internal negotiations. In other words, we’re not going to judge you, or at least we’ll try very hard not to judge you.

The other camp — and these are often the ones you’ll find commenting on articles and think pieces about feminism, even on this very site — have no interest in anything other than discrediting the movement. They’ve been the type responsible for the slings and arrows (and loogies and epithets) that feminism has fielded since its inception. These folks? They will judge you. But they’d be judging you whether or not your bold confession that watching “Keeping Up with the Kardashians” makes you feel like less of a feminist. Do you really want to give them specific ammunition?

When I got engaged to my husband 13 years ago, a few people asked whether I was going to have a “feminist” wedding. I answered that, in truth, I felt like the only significant way to impose feminism on a wedding would be to not get married at all. I had my reasons for choosing to go the marriage route, as most self-identified feminists do, but I didn’t feel the need to enumerate them then, and I don’t feel the need to do so now. But I understand why the question was asked, because marriage — and heterosexual marriage, certainly — is not a feminist act. Full stop. You can be the feminist-iest feminist around, but your all-male bridesmaids or Wiccan-Unitarian officiant do not, in themselves, have the juice to upend centuries of an institution in whose original incarnation women were just part of a property arrangement that also involved farm animals. It may be a wonderful, unique day for you and your betrothed; in the larger picture, however, your individual choice isn’t remaking that institution in a feminist mold.

But as feminism has become increasingly individualistic it’s given rise to the belief that one’s personal choices — where to live, what career to have, what culture to support — do add up to one’s politics. And weddings are a reliably fraught arena in which feminist identity is often a victim of unreasonably high expectations for subversion. Tracy Clark-Flory wrote a few months ago in Salon about the way her hope of an enlightened entrance into marriage slowly but surely bowed under the weight of the puffy-dress status quo. In “Where Did My Feminist Wedding Go?” Clark-Flory wrote that “Despite reading every book I possibly could on the tyranny of the wedding industry, I fell victim to it.” At the same time, she assured us that she wasn’t throwing a bouquet, being given away by her father, or changing her last name. Such articles seem to perform a fevered calculus in which everything about weddings — everything except marriage itself — is freighted with varying sizes of feminist baggage.

It’s worth noting that the writers of bad-feminist confessions pieces are almost always young, white and evincing a certain level of education and financial comfort. If you’ve ever read a progressive male writer struggling publicly to reconcile his love of, say, Crossfit or mixed-martial-arts competitions with his belief in anti-capitalism or anti-militarism, let me know. I haven’t seen one, and I don’t expect to. Many of these fellows surely have habits and pop-culture indulgences that don’t jibe with their political and social-justice leanings. But, to make a pretty sweeping generalization, they seem to get that those things need not be in lockstep. They just don’t seem to experience the quotidian compromises of their daily lives as fodder for tortured think pieces. Maybe it’s worth considering why.

Indeed, choice feminism as a whole has been the province of a specific kind of feminist. And I know I’m not the only person who has gotten a little weary of the idea that — as the Onion so famously put it — women are now empowered by everything a woman does. It is choice feminism that has gotten us to a place whereby one woman can be both a super-feminist and a traitor to feminism for choosing to, say, get a boob job.

The rise of these confessions seems to have less to do with an increase in the number of women realizing the limitations of choice feminism, and more to do with the demands of capitalism in the age of 24-7 content. Most of these essays appear on websites that rely on numerous daily updates and increasing page views; they’re another way to fill space that’s demanded by the constant need for new content. But the fact that women are the ones who answer this demand by mining their perceived failures in feminism seems to reflect a larger sense that feeling insecure, conflicted and even fraudulent is the realm in which female writers often receive the most validation.

Marriage, children, fashion, beauty, sex — all of these are places where we have become used to seeing women expose their lives to public scrutiny. From fictional characters like Bridget Jones and Hannah Horvath to historical self-obsessives like Mary MacLane to the real-life scribes on sites like xoJane, Jezebel and the Frisky, memoir has not only become an indelibly gendered form, but a literary brass ring that can be cannily gamed by the right person with the right story. It makes sense that young writers might look around and conclude that the best way to get their writing noticed is to come out with a few blazing rounds of recrimination and failure. But the failure can’t be too risky or high-stakes. Feminist failure, then, is perfect.

“Contemporary feminism often demands performance,” notes Roxane Gay in "Bad Feminist," “so when these women are writing these articles, they are, I think, performing their feminism. They're also trying to sidestep some of the more obvious criticisms they might face by putting the most vulnerable point out there up front.” Gay, while not among the young, white hand-wringers populating the blogosphere, does know from pondering feminist failure. She writes:

So much responsibility keeps getting piled on the shoulders of a movement whose primary purpose is to achieve equality, in all realms, between men and women. I keep reading these articles and getting angry and tired because these articles tell me that there’s no way for women to ever get it right. These articles make it seem like there is, in fact, a right way to be a woman and a wrong way to be a woman. And the standard appears to be ever changing and unachievable.

Gay also points out that “Feminism can, at times, feel rigid and not accepting of women as we actually live our lives. I openly embrace feminism that allows women to be human, flawed, and contradictory, but also feminists who believe in the equality of women from all walks of life. When we see these articles about bad feminists, we are perhaps seeing young women push back against some of the more rigid or perceived-as-rigid constraints of feminism as we have known it until now.”

Indeed, part of lived feminism (as opposed to the theoretical feminism quite a few of us learn as we take on the identity, often in college) is understanding that it is impossible to square our ideals of feminism with every aspect of our lives, and that it’s just not worth beating ourselves up over small capitulations to the entrenched patriarchy most carry around within us. But what I do want to stress is this: It is not helpful to write about each and every one, particularly not for an audience that, in large portions, is inclined to demonize feminism and feminists. Doing so begins to look like pointless self-flagellation. And — again, considering that huge numbers of commenters on any given feminist article are antagonists who have already reduced the movement to stereotypes — it trivializes feminism, making it look even more like the exclusive realm of elite women who are squandering time and energy bickering over whose shoes are more authentic to the sisterhood.

So say it with me: Not everything a feminist does is a feminist act. You are large. You contain multitudes. And you are under no orders to reveal those multitudes to thousands of readers and commenters who already want to discredit you. Feminism is more than a collection of personal likes and dislikes. And that’s why choice feminism as a whole is a dangerous frame for a political and social movement. If everything is feminism, then nothing is. And if we feel the need to disavow everything we do and everything we desire, how much easier is it to discount what we claim to really want?

All these bad-feminist articles do is reinforce the belief that feminism is the purview of a legion of judgy women policing the mostly superficial choices of others. No one wants to submit to a purity test, because everyone would fail. Look at the history of the women’s movement, filled with people who had strong and commendable ideas and goals but who were also bigoted, intolerant and had terrible taste in music. Margaret Sanger was a eugenicist. Susan B. Anthony was racist. Betty Friedan was a notorious homophobe who, unrelatedly, once chased her husband down a Fire Island beach with a knife. Acknowledging these things doesn’t discount their achievements; all it does is make them human.

There’s a line in the sand somewhere, of course; for instance, if you are actively working to deny equal rights and/or bodily autonomy for women, calling yourself a feminist is ridiculous, since your political positions run counter to the very definition of it. (Ahem, Sarah Palin.) But the fact that you enjoy the “unfeminist” musical stylings of Taylor Swift? That does not impact the nuts-and-bolts status of gender equality. There’s no reason to atone, publicly or privately, for it.

In the end, neither of the two assertions that characterize choice feminism — “I’m a bad feminist for doing X,” and the flip side, “X is a feminist act” — is particularly helpful to either defining what feminism is or arguing that it remains a relevant political and social identity. If, say, wearing high heels or having short hair or feeling flattered by catcalls is what makes or breaks your feminism, perhaps it’s more fragile than you think.

Andi Zeisler is the cofounder of Bitch Media, and has been writing about feminism and popular culture for 18 years. She watches a lot of E! Find her at @andizeisler.

Shares