In the inaugural post for his new blog at the Intercept, former Washington Post reporter and Huffington Post bureau chief Dan Froomkin makes an argument that is pretty widely held by opponents of the post-9/11 national security state, but still deserves our closer inspection. If we take a hard look at Froomkin’s idea, we’ll find that while it carries with it elements of truth, it ultimately misses something fundamental about the character of the United States — something that explains our political class’s overheated rhetoric about ISIS, and why truly ending the war on terror will be harder than many of us once believed.

First, though, let’s look at Froomkin’s argument, which goes more or less like this: Due to weakness or villainy, President Obama has continued many of the anti-terrorism policies embraced by his predecessor, policies that are the result an understandably traumatized people’s desire for safety in the wake of the September 11 attacks, and which are themselves an unethical break from tradition. As Froomkin puts it, Bush’s “extremist assault on civil liberties, human rights and other core American values” was supposed to be “an aberration” in U.S. history, but instead has been “institutionalized” under Obama.

The result of this institutionalization, Froomkin claims, is that returning government “to a pre-Bush-era respect for basic human dignity and civil rights” will be “a hard, long fight.” The window for erasing Bush the younger from American history is closed, Froomkin implies, and we are all now stuck in the forever war and panoptical surveillance state that Bush, Cheney, Rumsfeld and the rest gave us. Obama blew it, and now “the hopes for any change are slim.”

Now, here’s where ISIS comes in. As the media debate over what is to be done with the extremist group continues to unfold, I can’t shake the feeling that Froomkin’s vision of an idyllic pre-Bush America — where “respect for basic human dignity and civil rights” reigns supreme and where a “rejection of decision-making based on fear” is a reasonable expectation — unknowingly blames wild emotion and the office of the presidency for mistakes that, in truth, resulted from a toxic mix of psychology and ideology that is seductive to us all. To tweak Shakespeare: The fault, dear reader, is not in our politicians, but in ourselves.

Before we start apportioning blame, however, we should better understand the “toxic mix” that is so prevalent right now in the ISIS debate. The sentiments being combined are our psychological need as human beings to feel our lives have meaning, and our ideological need as Americans to feel that our country is an instrument of Providence (or Progress, as secular people call it) that spreads justice and liberty throughout the globe. Taken in isolation, neither of these two impulses are necessarily bad. There are virtues to seeking a life worth living; and the belief in America as a chosen nation can sometimes compel us to hold ourselves to a higher standard. But when they’re combined, as they have been by many of those who are most vigorously promoting yet more war, the result — a belief that, in order to lead the world, America can and must vanquish evil — can be fatal.

When it comes to fitting ISIS into the role of cosmic evil that the "good" are obligated to fight (i.e., turning ISIS into what John Quincy Adams once called a “monster to destroy”) there’s plenty of material to work with. ISIS’s beliefs and practices are nihilistic and cruel in the extreme, and their propensity for genocidal violence is all too well documented. Anyone who doubts the nightmare that would be a world in which ISIS is more than a stateless, abnormally large paramilitary group — and is instead an actual nation-state with an actual army and an actual reliable source of revenue — is advised to read this remarkable and harrowing report of how one man survived an ISIS massacre. Many of these men behave like bloodthirsty monsters, make no mistake.

Yet because so few people, even hawks, would agree with the idea that the U.S. should destroy all forms of evil across the globe, those who seek to imbue their lives with meaning by demanding other people kill the “bad guys” must persuade the rest of us that the ISIS threat is existential in nature, one America and the world cannot ignore and must squarely face. Anyone who’s been near a cable news-playing TV or a Twitter timeline lately is familiar with the process; but for those blessed enough to be insulated from the hysteria, here are some examples of the arguments offered by those who want war against ISIS. They tend to go something like this:

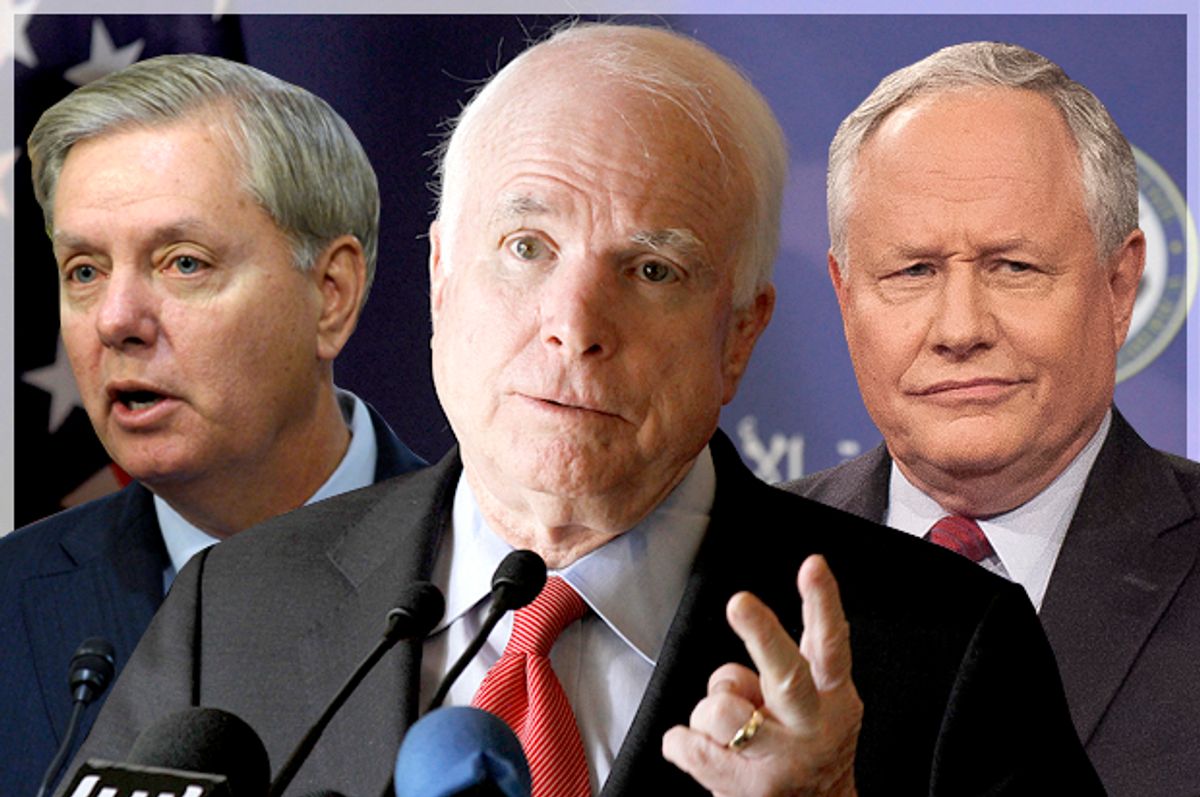

- ISIS, according to Sen. Lindsey Graham, is “a direct threat to our homeland,” one that is “coming” to our shores.

- “They are getting stronger all the time,” Sen. John McCain warns. “[T]heir goal, as they have stated openly time after time, is the destruction of the United States of America.”

- “[I]n my lifetime we have not seen a more grave threat to America and to democracies worldwide [than ISIS],” tweets Mia Farrow, the actress who’s now nearly as well-known for her activism in support of human rights.

- The danger represented by ISIS is so serious, Bill Kristol says, that it justifies a bomb-and-see approach: “What’s the harm of bombing them at least for a few weeks and seeing what happens?”

- “Simply put,” writes Quartz’s Bobby Ghosh, “[ISIS] is an unholy combination of al-Qaeda, the Khmer Rouge, and the Nazis.”

In all of the examples above, as well as the countless more that have gone unmentioned, ISIS is described not only as a world-historic evil, but one that (somewhat paradoxically) the United States can easily defeat, if it would only make the effort. Kristol’s quip about “seeing what happens” after dropping yet more bombs in the Middle East may be extraordinary for its glib hubris, but it’s merely an unpolished expression of the idea behind so much of the criticism being sent the president’s way for his “we don’t have a strategy yet” gaffe — namely, that there is a military strategy to defeat ISIS, somewhere in the ether; and that the president and countless regional experts are mistaken when they say ISIS is fundamentally a political problem, one that only Iraqis and Syrians themselves can solve.

Whether they know it or not, the people making these arguments simply assume that evil can be defeated. And whether they know it or not, they also assume that America can and must be the one to do it. Embedded in these assumptions is a rejection of those who’d argue that the world is too complex and unruly for any manmade entity to bring to heel. Also rejected are those who’d go even further, arguing that evil of the kind ISIS represents can never truly be defeated, can only ever be thwarted, managed and guarded against. In both cases, what’s really being rejected, on a deep psychological level, is the idea that the universe is far less under our control than we’d like to admit, and that each and every one of us — including even the president of the United States — is not really participating in a grand struggle of good vs. evil so much as just trying to hold on.

Of course, far from every American holds the worldview I’m describing. In fact, if you look at polling of the general public, a clear majority believes the U.S. is too involved in the affairs of other countries, too interested in acting as lawmaker and policeman for the rest of the world. So if America were a real democracy, a place where the views of elites mattered little more than those of the 99 percent, Froomkin might be right to imagine a recent past and distant future in which the war on terror — with all its military adventurism and its rollback of civil liberties — had actually ended, instead of merely switching to another name. And in the present moment, unfortunately, that is decidedly not the case.

Shares