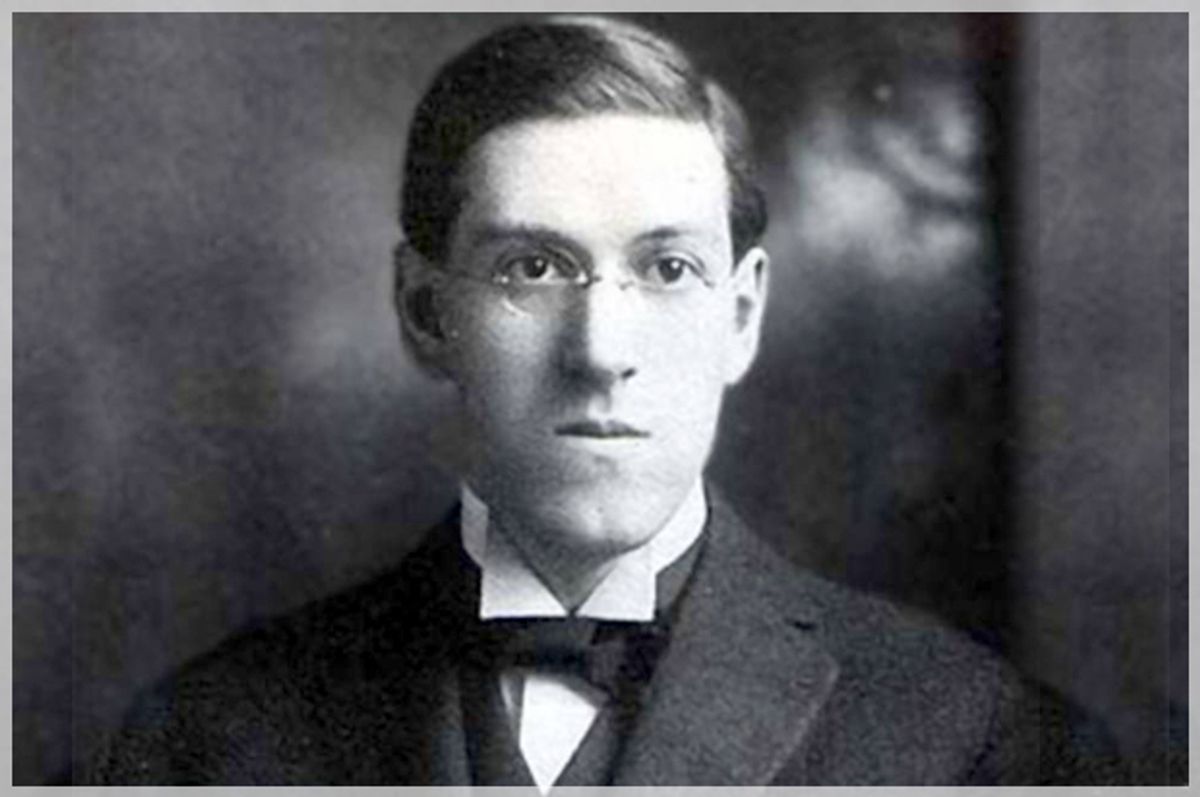

The World Fantasy Awards, presented at the World Fantasy Convention every fall, have been around for almost 40 years. The trophy for such categories as Novel, Short Fiction and Anthology is a caricatured bust of H.P. Lovecraft, author of such classics of weird fiction as "At the Mountains of Madness" and "The Call of Cthulhu." Lovecraft is a beloved figure in pop culture, and an influence on everyone from the Argentinian metafictionist Jorge Luis Borges to the film director Guillermo del Toro, as well as untold numbers of rock bands and game designers.

But not everyone who wins a "Howard" likes the idea of keeping Lovecraft's face around the house. Nnedi Okorafor, who won the WFA for best novel in 2011 ("Who Fears Death"), wrote a blog post about her discomfort with the trophy after a friend showed her a racist poem that Lovecraft wrote in 1912. Enough dissatisfaction has accumulated to inspire another writer, Daniel Jose Older, to petition the WFA's administrators to change the award to a bust of the late Octavia Butler, an African-American author more commonly identified with science fiction.

Whether or not Butler would be the right choice (other commenters have suggested a non-portrait design), what's most surprising about the ensuing debate over the proposal is how defensive it has made some members of Lovecraft's extensive following. The fuss has accentuated some of the shortcomings of our increasingly fan-driven culture.

To anyone who's read all of Lovecraft's fiction plus even a smattering of biographical material, his venomous racism is self-evident; it's right there on the page. (For a more detailed examination of the author's prejudices as expressed in both work and life, see Phenderson Djeli Clark's excellent essay "The ‘N’ Word Through the Ages: The ‘Madness’ of H.P. Lovecraft" at Racialicious.) A writer of intense, morbid and cloistered passions, Lovecraft expressed a pervasive disgust with physical existence itself, as well as the cosmic dread for which he has often been celebrated. Yet he reserved his most intimate revulsion for those human beings he regarded as, for example, "a bastard mess of stewing Mongrel flesh without intellect, repellent to the eye, nose and imagination," to quote just one typical description (in this case of New York's Chinatown), from his letters.

Perhaps the most egregious response to the WFA petition has come from the prominent scholar and Lovecraft biographer S.T. Joshi, who posted several responses to Older's campaign on his blog. A remarkable combination of the pompous and the grotesquely arch, these salvos have the unconvincing hauteur of someone who wishes to appear wittily above the fray when in fact he is angry and not about to drop it any time soon. ("I suppose the poor fellow is unaccustomed to intellectual debate. It is true that my response may have been the equivalent of swatting a fly with a sledgehammer — but it was the principle of the thing, you see," etc.)

Yet even Joshi cannot deny that Lovecraft was racist. Instead, he strives to portray this fact as immaterial for reasons that include: Everyone was racist back then; Lovecraft's racism was perfectly natural when you consider his upbringing; getting upset about Lovecraft's racism serves no purpose; there are many other aspects to Lovecraft's life and work; anyone who knew anything about Lovecraft would be aware that he was a smart guy who was generous to his friends; and, finally, "the WFA bust acknowledges Lovecraft’s literary status in the field of weird fiction and nothing more. It says nothing about Lovecraft’s personality or character." (The contradiction between the last two points -- if Lovecraft's personal behavior is irrelevant to Older's complaint, then it's also irrelevant to Joshi's defense -- apparently escaped the biographer.)

Some of Lovecraft's defenders in this matter are probably bigots themselves. ("If his racism was necessary for him to create those brilliant works of art, than [sic] thank god for his racism," one commenter wrote. "It cannot be surprising that a man who so valued architecture and the written word would have issues with cultures which [sic] had never mastered either, such as that of Africa and Native America.") But others simply feel that their hero has been attacked and wish that critics would stop talking about it. David Nicke, author of a "pseudo-Lovecraftian" novel, "Eutopia," reported on his blog that he attempted to raise the topic of Lovecraft's "xenophobia" on a couple of panels at horror and science fiction conventions and was politely but firmly shut down.

We live in a culture increasingly dominated by fandoms, and while the enthusiasm of fans can be invigorating it's not always conducive to critical thought. When we love a writer's work -- and I must confess that I do love Lovecraft's, if not everything about it -- we often have an attendant and childish desire to idolize its maker. In Lovecraft's case, this impulse is particularly perverse because the power of his fiction derives from the hot mess of its creator's psyche. Like Poe, Lovecraft speaks to a gnarled, doomy and phobic corner of human nature that all of us visit from time to time.

This is leavened by the undeniable camp appeal of his prose style, with all its wheezing, creaking, gibbering, florid and hilariously hyperbolic excesses: "I felt the strangling tendrils of a cancerous horror whose roots reached into illimitable pasts and fathomless abysms of the night that broods beyond time." Some readers cannot tolerate such cavalcades of bossy adjectives; the critic Edmund Wilson once complained, "Surely one of the primary rules for writing an effective tale of horror is never to use any of these words -- especially if you are going, at the end, to produce an invisible whistling octopus.” Which is a fair cop ... and yet, and yet. For the Lovecraft buffs I know, the silliness is a significant part of the charm.

If there was ever a writer who should not be taken too seriously, it's this one. Although Lovecraft's stated theme -- the terror of confronting the insignificance of humanity in an unfeeling, unthinking universe -- is as heavy as it gets, the latent content of carnal, particularly sexual, revulsion often threatens to take over. The oozing goo, the primordial squids! Whatever Lovecraft thought he was doing, he wasn't big on self-awareness, or else he'd have been Beckett. Freud and his theories of repression and sublimation become impossible to resist when you're tracing this author's energy to its source -- that is, to all the stuff Lovecraft was avoiding thinking about while allegedly facing the unthinkable. This is what makes his fiction go.

And race is part of it. Lovecraft's contempt for and horror at what he saw as the degraded, brute physicality of non-WASPs was really his dread of physicality itself. Like most racists -- and despite the "man of his time" defense, Lovecraft was worse than many of his day -- the loathing he directed at others was a deflected form of self-hatred. That doesn't excuse it, any more than you get a pass on kicking a puppy because you had a bad day at the office.

The unsavory manifestations of Lovecraft's dread can't be surgically removed from his fiction by an act of willful blindness, as some fans seem to think. (And of course, it's a lot easier to ignore the hateful elements of someone's work when it's not directed at people like you.) To the contrary, they help us to understand it, but to do that we need to be able to accept the truth that even great artists -- greater ones than Lovecraft, certainly -- have their ugly sides, and that ugliness can be inextricable from their greatness. Art, being human, is an expression of the whole self. This isn't the same as accepting Lovecraft's racism. You can acknowledge, contemplate and discuss that racism without feeling obliged to reject the work as a whole.

Every fan needs to grow up eventually. Those who rage at writers who call attention to Lovecraft's racism are as petulantly territorial as the tantrum throwers harassing the feminist video-game critic Anita Sarkeesian for daring to point out demeaning depictions of women in that medium. Sarkeesian prefaces her video critiques by noting, "As always, please keep in mind that it's entirely possible to be critical of some aspects of a piece of media while still finding other parts valuable or enjoyable." Who needs to be told that? Too many of us, apparently.

Of all the people currently expressing their reservations about Lovecraft and the WFA trophy, I've yet to find one who's telling others to stop reading him. In fact, most of these critics continue to enjoy his work for its imaginative scope, gothic sensibility and any number of other reasons. The World Fantasy Award, however, is another matter. It's an expression of the values of a community, not a reader's private choice. When Joshi writes, "If Nnedi Okorafor and China Miéville [another WFA winner who objects to the trophy] are so offended at owning the WFA, they should simply return it and be done with the matter," he is essentially telling writers like Okorafor that they must accept an honor from that community in the form of a man who considered them to be "semi-human" and filled "with vice." Suck it up, or get out. I'm pretty sure this is not the message the World Fantasy Convention meant to send when they gave Okorafor the prize in the first place.

Shares