LIMA, Peru — Expressing intense differences of opinion at Ivy League universities is not exactly new. It is actually the schools’ lifeblood.

LIMA, Peru — Expressing intense differences of opinion at Ivy League universities is not exactly new. It is actually the schools’ lifeblood.

But it’s not every day that you hear an eminent Harvard professor accused of being a “bandit” and “financial hit man.”

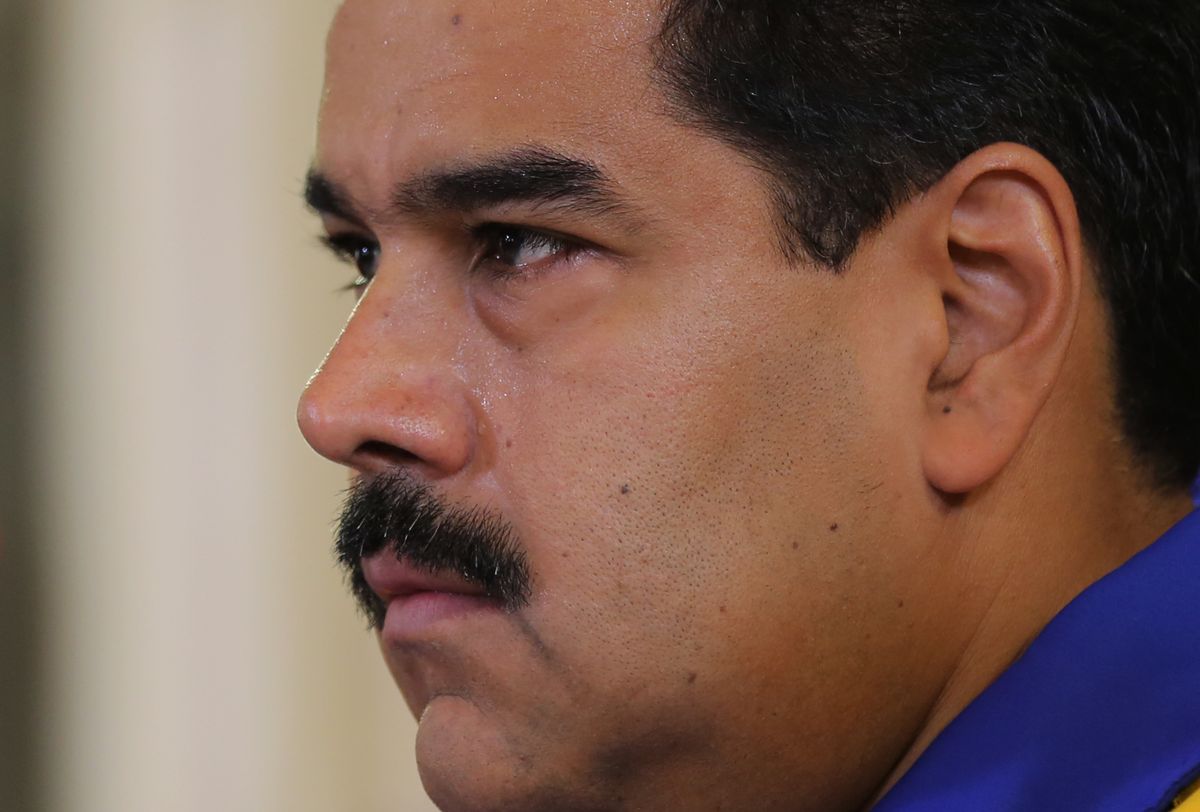

That’s how Nicolas Maduro, Venezuela’s beleaguered and increasingly thin-skinned president, reacted last week to an opinion piece co-authored by economist Ricardo Hausmann about whether the nation should default on its debts.

The article reportedly even contributed to a drop in Venezuela’s bond prices.

Maduro, political heir to Hugo Chavez, instructed Venezuela’s attorney general to take unspecified “actions” against Hausmann, who heads Harvard’s Center for International Development and is a former Venezuelan planning minister.

Hausmann, you might think, has good reason to worry about the Venezuelan economy. Inflation is around 60 percent. The official fixed bolivar-to-dollar exchange rate is less than a tenth of the black market rate. And the country is plagued by shortages of a lengthy laundry list of basic necessities, from bread to cancer drugs.

Meanwhile, Venezuela has one of the world’s highest murder rates, with rich and poor fearing to leave their homes even in broad daylight.

The governments of Maduro and his late mentor Chavez have managed all that despite Venezuela having the world’s largest oil reserves.

The Harvard prof has history with the Chavistas. Hausmann’s brief time in office was in the elected but deeply unpopular government that Chavez sought to overthrow by force in 1992.

That coup failed and the brash young army colonel was jailed — but not before he gave a televised speech that rocketed him to fame and effectively launched his successful 1998 presidential run.

Since taking office last year, Maduro has ramped up Chavez’s intolerance for criticism, rights groups say, jailing several opposition leaders and overseeing the closure of critical TV and radio stations.

But what may really have hit a nerve with the president is Hausmann’s suggestion that the government’s insistence on honoring its debts to wealthy bondholders is hurting ordinary citizens.

“The fact that his administration has chosen to default on 30 million Venezuelans, rather than on Wall Street, is not a sign of its moral rectitude,” wrote Hausmann and co-author Miguel Angel Santos. “It is a signal of its moral bankruptcy.”

That’s a blow to Chavismo — which claims to rule on behalf of Venezuela’s long-neglected poor majority.

Maduro’s rant brought a predictable rallying around Hausmann. Harvard accused the president of intimidation.

“It is in the open exchange of opinions and ideas that people and nations can learn and prosper,” the dean and provost of the Kennedy School, where the professor is based, said in a statement.

Meanwhile, academics and other supporters penned a sharp open letter backing Hausmann and accusing the Maduro administration of confusing “dissent with treason.” Signatories included Mexico’s last president, Felipe Calderon, a Harvard fellow himself.

Hausmann was on a plane as GlobalPost worked on this story. But in earlier comments to Bloomberg News, he slammed Maduro’s scare tactics.

“This is Exhibit A in how Venezuela is not a democracy,” Hausmann said. “He [Maduro] uses his position as head of state to intimidate people who think differently.”

Maduro’s televised fury will do nothing to fix his country’s sinking economy. Many economists say Venezuela’s desperate situation appears set to get worse before it gets better.

In a cabinet reshuffle earlier this month, Maduro even ousted his oil minister, Rafael Ramirez, viewed as a pragmatist who favored reforming the “Bolivarian” socialist economic policies that have driven the country to ruin.

“He was the one person in the government that had at least been floating balloons about reforming the exchange rate or raising gas prices,” said Harold Trinkunas, a Venezuela expert at the Brookings Institution, a Washington, DC foreign policy think tank.

Shares