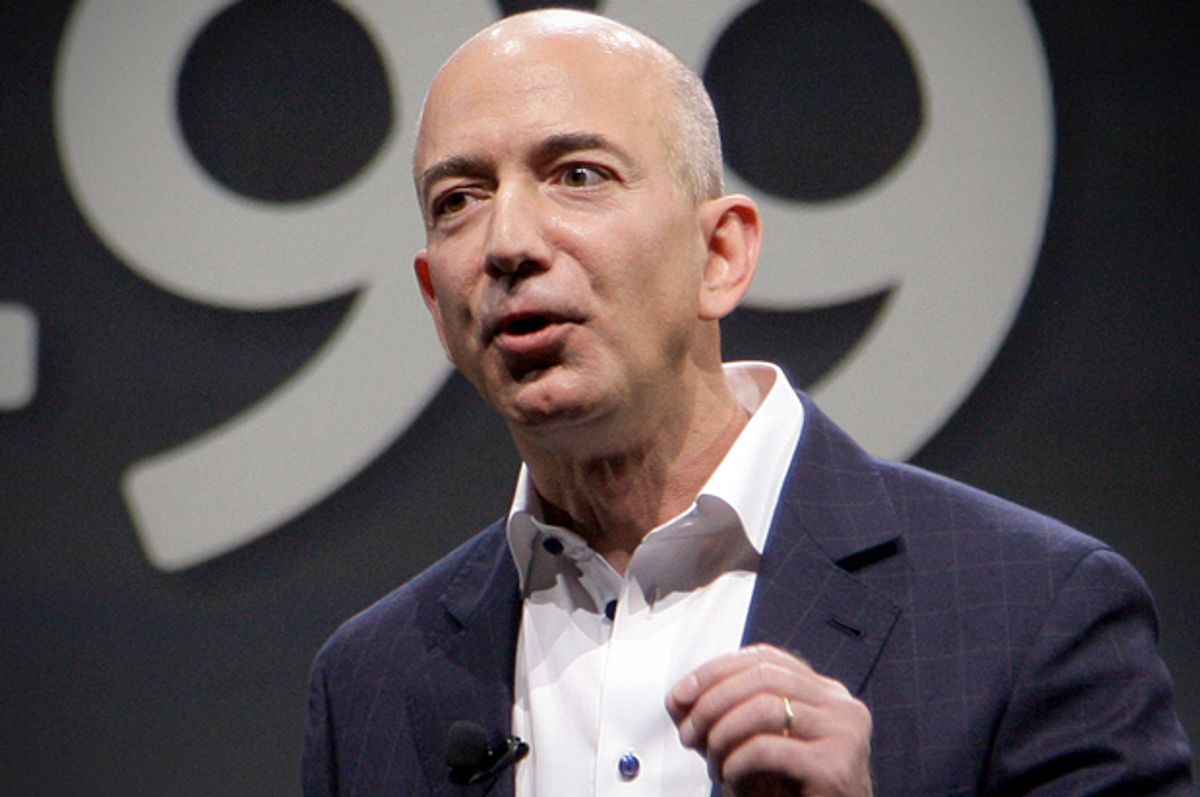

Jeff Bezos, the billionaire founder and CEO of Amazon, is well-known for his almost spiritual belief in the benevolent powers of innovation (the word the 1 percent likes to use when the hostile implications of Silicon Valley's preferred term, "disruption," risk alienating them from their audience). And it's indeed the case that Bezos' creation has been a leader in the corporate world when it comes to doing things like no one before. Amazon Prime, the Kindle, 2-day delivery; the list goes on.

There's an addendum to that list, however, and it's one that, shareholder updates excluded, Bezos and fellow Amazon higher-ups are considerably less vocal in promoting: The company's longstanding habit of finding creative new ways to exploit and insult its workers. And that's the version of Amazon-the-Innovator that will stand before the Supreme Court today as it hears oral arguments for Integrity Staffing Solutions, Inc. v. Busk, one of the biggest labor rights cases of the term.

To get a sense of the specifics of the case, as well as its potentially far-reaching implications, Salon spoke on Tuesday with Catherine Ruckelshaus, general counsel and program director for the National Employment Law Project. Our conversation is below and has been edited for clarity and length.

We tend not to hear much about Supreme Court cases until there's an imminent ruling, much less before oral arguments have begun. So could you give me a quick overview of the case?

Sure. This is a case that's been brought by Amazon warehouse workers who were working in a warehouse in Nevada and who at the end of their shift every day were required to go through an anti-theft screening in the warehouse that took workers as much as 25 or more minutes to get through.

So the workers brought a lawsuit against the staffing company that Amazon has [contracted] to recruit and hire the workers, it's called Integrity Staffing [Solutions], and sued to try to get paid for the time they stood in line at the end of their shifts.

The [United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit] said the workers should get paid for that time, and the employer appealed and the Supreme Court has now taken the case.

The argument for the workers seems pretty intuitive to me; if you're doing something because of your employer's demand, you should, within reason, be compensated for your time. What's Integrity's argument in response?

The employer and, surprisingly, the government are saying that because the duties are not "integral and indispensable" to the regular duties that the workers are performing, the work isn't compensable. So they're trying to carve out of any duties that workers would perform whether or not it's at the direction of the employer — or for the benefit of the employer — if they're not "integral and indispensable" then you don't have to get paid for it.

When news broke that the Obama administration was siding with the employers in this case, was that your expectation? Or was it a surprise to you and others in the field?

Yes, we were very surprised. The position that the government's taking is directly contrary to some of the Department of Labor rulings and regulations, so it's very confusing and surprising to us. And it certainly doesn't square with what the administration has been saying, and taking steps on, around minimum wage and trying to advocate for ... more money in the pockets of low-wage workers, in particular.

And what Amazon did here — contracting out hiring to another company and then having that company enforce Amazon mandates — is becoming increasingly common, right?

Yes, the practice of outsourcing (or using a temp or staffing firm) to [hire] employees is increasingly common. More and more employers are using it either to evade labor standards or just to avoid the headaches they perceive as attendant to having a large workforce. So the fact that Amazon is using a staffing firm like Integrity Staffing isn't unusual.

I think it's telling that Amazon has basically instructed staffing companies that they have to do these anti-theft screenings, and then the staffing companies do that and don't pay their workers. So that's the part that's a little disturbing — that [the screening] is required by Amazon but the workers aren't getting paid for it.

Given the makeup of the current Court, I can probably guess, but how are people expecting the Court to come down on this case, barring something extraordinary happening during oral arguments?

I think what the Supreme Court is actually being presented with are two almost "ships passing in the night"-kind of arguments.

The government and the employer, as I said, are focusing on this "integral and indispensable" [language], so if you play out that argument, your employer could ask you to mow their lawn — and that might not be related to your work, but if your employer asks you to do it, you have to do it and it's not compensable. So there are some pretty outrageous things that could flow from their purported test.

The workers' attorneys are arguing that we [shouldn't] even get to the "integral and indispensable" piece of the argument because the case raises the question of what is work — and work is anything that's directed by the employer and benefits the employer, and that's compensable no matter what.

The Supreme Court could decide in favor of the workers, even though it looks like it might not, given that it's going to review the Ninth Circuit's reasoning, which went in favor of the workers. But I think it could go the way that the workers are arguing, which is that this is work because the employer ordered it and is benefitting from it.

I suppose this is nearly always true when it comes to cases that reach the Supreme Court, but it sounds like the potential implications of the Court's ruling — no matter which way it rules — could be pretty significant.

They could be, it's true. If the Court takes the government and employers' positions, there are going to be a lot of duties that employers are going to be permitted to require of their workers, who wouldn't have to get paid for [their time].

One thing that's striking to me in this case, too, is that it's about 25 minutes per-day, which is over 2 hours a week, but [Amazon/Integrity Staffing] could create more security screening positions in the workplace and it could be much quicker — it could be 5 minutes, 3 minutes... But because it's free in the eyes of the employers, they're not paying attention to it, they're taking it for granted, and they're not trying to make it more efficient....

If the Court ends up ruling that this kind of time spent [by workers] isn't compensable, then I think we're going to see a lot of other employer practices requiring workers to work off the clock and not get paid for it.

Amazon and Integrity Staffing may think of it as free, but it sounds like what they're basically doing is having their workers pay for it instead by sacrificing their own time and energy.

Right, and if it's something de minimis, like 2 or 3 or even 5 minutes a day, no one's going to complain and this wouldn't even be an issue before the Court. ... And there are other lawsuits around the country challenging this same practice by Amazon, in Pennsylvania and other states, and they're all complaining of these really long wait times.

Now, is the potential precedent the Court could establish here allowing employer's to decide what's compensable or not — is this something that white-collar and professional workers should be concerned about? Or is this something that's only pertinent to those who work in the corners of our economy where many of us would rather not look?

I think if you played out the rationale of the government's position and the employer's position, you could [imagine] nurses who at the end or beginning of their shift have to clean up the trash cans in hospital rooms.

Or you could think of even white collar workers who might be financial analysts on Wall Street but whose bosses say, "I really need you to go pick up my dry cleaning at noon..." or "Can you take my daughter to my violin class..." That's not "integral and indispensable" to a financial analyst's job, but they could still be required to do it and it could take up a lot of time [and] not be compensable under this [potential] ruling.

You could play it out in a lot of different scenarios where workers who are actually pretty high-paid could be required to do duties that aren't part of their job description and for which they still wouldn't be paid.

And that really gets to part of the larger significance of the case, which is that in a fundamental way it's about the balance of power between employers and workers.

That's right. And again: If we don't have to pay for things, we take them for granted, and we don't care about them, and that's what's happening here. It's a relatively easy fix for an employer like Amazon to put in a couple of other anti-theft metal detectors (or whatever they're using) and they just haven't done it. Because they don't care.

UPDATE (10/08/2014, 11:57 a.m.)

In response to the interview above, Amazon has provided Salon with the following statement: "We have a longstanding practice of not commenting on pending litigation, but data shows that employees walk through post shift security screening with little or no wait."

Shares