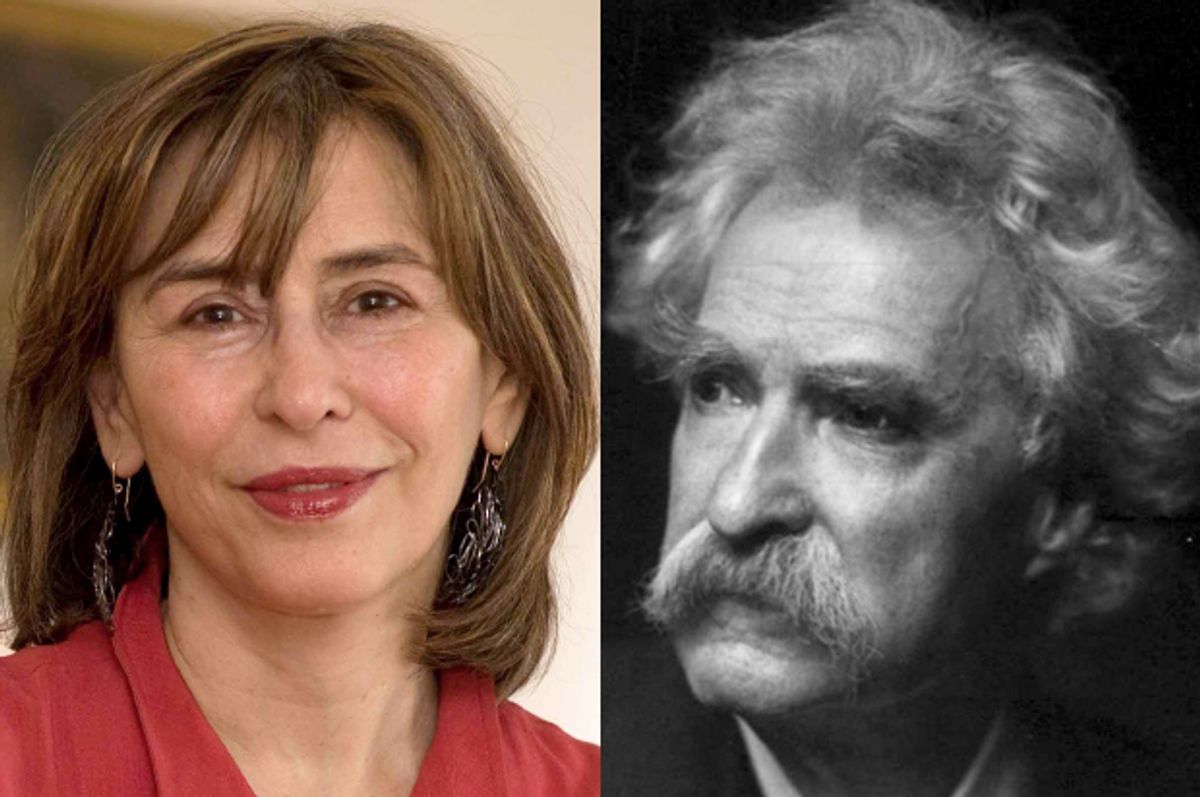

Sometimes it takes an outsider to see us plain. This holds true even when the "us" crying out to be brought into focus already thinks of itself as a nation of outsiders. That's the premise of Azar Nafisi's new book, "The Republic of Imagination: America in Three Books," a series of linked essays that explores the U.S. through its literature. Nafisi -- an Iranian who attended college in Oklahoma in the 1970s, then returned to her homeland to teach English literature in Tehran after the Shah was deposed -- eventually had to flee as the Islamic regime became increasingly oppressive.

Nafisi's account of her years of teaching in Iran, "Reading Lolita in Tehran," was a runaway bestseller in 2003. She became an American citizen five years ago, but her passion for American culture began when she was just a child and her English tutor read aloud to her from Frank L. Baum's "The Wonderful Wizard of Oz." America was, for her and many Iranians of her generation, a land of phantasmagorical and perilous freedom.

Now, in "The Republic of Imagination," Nafisi argues that the best aspects of that America are being allowed to wither away. Her first book offered an often-flattering juxtaposition of the Western literary ethos of personal liberty against the totalitarian fundamentalism of the Islamic Republic of Iran. Here, however, is where Nafisi calls Americans -- left and right -- to account for abandoning a glorious cultural legacy to wallow in materialism, narcissism and groupthink.

That said, while parts of "The Republic of Imagination" are polemical, much of it is personal and evocative. Nafisi is a master essayist who sinuously weaves together elements of memoir, criticism, biography and history; you don't realize how completely these topics interpenetrate each other until you come to the end of a chapter or section, often (at least in my case) with eyes stung by tears. No one writes better or more stirringly about the way books shape a reader's identity, and about the way that talking books with good friends becomes integral to how we understand the books, our friends and ourselves.

Huck Finn embodies the first of three aspects of the American character Nafisi addresses in "The Republic of Imagination." For her, Twain's wandering, runaway boy hero represents "America's vagrant nature ... our vagabond self." Her unfurling case for Huck as the moral exemplar of a nation comes twined with an account of her friendship with Farah, a woman she knew from childhood. At one point, the two friends laugh over what Huck himself would make of two middle-aged Iranian-American women spending so much time talking and thinking about him. When Farah learns that the cancer she's been battling is terminal, she even talks her husband into getting a dog that she promptly names Huck.

It's only later in this section, when Nafisi recounts Farah's harrowing departure from Iran, that the connection becomes obvious. Farah's husband -- involved with an activist group that had first agitated for the ouster of the Shah, then resisted the burgeoning authoritarianism of the Islamic Republic -- had been arrested and imprisoned. Farah herself was seven months pregnant. With a small group of friends, she made a desperate journey through mountains and deserts on horseback and (when their hired guides abandoned them) on foot to the Turkish border. Like Huck, both Nafisi and Farah fled a society that had become -- as Huck would describe the respectable households of St. Petersburg, Missouri -- "smothery." (Literally, in fact: Nafisi was fired from the University of Tehran for refusing to wear the veil.)

Huck personifies what Nafisi loves most in American culture: principled independence. When Farah grew ill, "Huck was our guide, our inspiration, the thorn in our side who reminded us to be true to ourselves and who goaded us when we became too complacent, too conventional in our preoccupations, whenever we seemed too comfortable with our lot." For Nafisi, the quintessentially American moment when Huck decides that he will do what he has been taught is "wrong" -- that is, help his enslaved friend, Jim, to freedom -- is the instant when "the authority of the outside world is replaced with an inner authority." Huck chooses to act out of the instincts of his heart rather than according to a received code. It is also the point where the responsibility to correct a great wrong shifts off of society and "onto us, ordinary people, who can so unwittingly participate in the implementation of unspeakable crimes."

It isn't hard to see how this humanist impulse would speak to a refugee from a totalitarian state. Nafizi believes an aversion to this type of independence also underlies the Iranian regime's crackdown on detective fiction. A Raymond Chandler fan, she notes that the government is "so uncomfortable with scrappy gumshoes like [Philip] Marlowe. How could such a character be permitted in a dictatorship -- someone who stands witness to police stupidity and (in the case of the American detective story) corruption in high places?" Marlowe is a skeptic, and although at first glance the lineage may not be the most obvious, Nafisi sees him as one of Huck Finn's "progeny."

Tom Sawyer, on the other hand, she does not like at all. Behind his trickster antics, Nafisi identifies a fundamentally conventional personality. Tom, she believes, is the antecedent -- in another of her daring but persuasive linkages -- to Sinclair Lewis' George Babbitt. In the middle section of "The Republic of Imagination," that upstanding, go-getting, bootstrapping early 20th century Rotarian businessman becomes the emblem of all that is misguided, venal, selfish and blinkered about Americans. Lewis' novel also provides Nafisi with the occasion for a splendid, oratorial denunciation of all that is utilitarian in American education, from the cutting of art and music courses at the elementary school level to the declining support for the liberal arts at universities.

Nafisi's stormy condemnation coalesces around one David Coleman, who headed the nonprofit organization that formulated the Common Core State Standard for K-12 education under the Obama administration. It's almost possible to feel sorry for Coleman, as Nafisi goes on to paint him as an unqualified, feckless and quite possibly soulless philistine intent on turning American schoolchildren into a nation of mini-Babbitts designed to serve as docile "workers in the global economy." (Almost, but not quite!) Under Coleman's ethos of "data-driven instruction," even the study of such seminal texts as the Gettysburg Address have been stripped of social and historical context, as well as the potential for subjective interpretation.

The villains in this section of "The Republic of Imagination" are mostly Republican lawmakers, like Florida Gov. Rick Scott, who views education as a strictly vocational enterprise that ought to focus exclusively on STEM (science, technology, engineering and math) training. (Bill Gates comes in for a drubbing as well.) By contrast, even within the fields of tech and science, Nafisi points out, the most influential figures -- ranging from Einstein to Steve Jobs -- understand that the root of genuine creativity is a love of knowledge for its own sake. No one put it better than Robert Wilson, the founding director of the Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, who when asked by Congress to explain how a new particle accelerator would contribute to national defense, said, "It has nothing to do directly with defending our country, except to make it worth defending."

As Nafisi observes, even Babbitt, that crass, materialistic striver, harbors a stifled but never entirely suppressed hankering after meaning. Poets, writers and artists, as she argues, speak to and for this element of the human spirit, the part that enables Huck to defy damnation to do what he knows in his heart, if not his head, is right. That's why totalitarian dictatorships lock them up. The kinds of citizens produced by Coleman's program would most likely be biddable, diligent cogs in the massive machine of global capitalism, but they'd also be defective citizens. Such stunted souls would be unable to formulate a moral resistance to the bad deeds of their employers or government because their inner lives -- the gardens where morality, discernment and empathy grow -- would be largely uncultivated.

The third part of "The Republic of Imagination" considers Carson McCullers' "The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter," a novel about a collection of misfits who cluster around a deaf-mute man in a Southern town. The book reminds Nafisi of a college friend, a Southern artist, who also loved it, and who insistently reminded the young, exuberantly politicized Nafisi that fiction is as much about sensuality, atmosphere and aesthetics as it is about ideas. For Nafisi, their conversations about Edward Hopper's paintings and McCullers' novels led to an obsession "with the different forms of loneliness in American art and fiction and their relation to a certain idea of America." Her friend, on the other hand, pondered how she could paint the heavy Southern heat that McCullers so excelled at invoking.

Nafisi's friend always insisted that as a non-Southerner Nafisi could never truly understand McCullers' books. Nafisi herself is not so sure. She believes that one of the purposes of art and fiction is to transcend the boundaries of identity, and this becomes the theme of the remainder of "The Republic of Imagination." Nafisi challenges the academic thinkers who have tried to force her into a restrictive role defined by identity politics. The figure of James Baldwin presides over the book's epilogue, with his famous condemnation of "the protest novel" as a work whose failure lies "in its rejection of life, the human being, the denial of his beauty, dread, power, in its insistence that it is his categorization alone which is real and cannot be transcended."

Nafisi -- whose previous book was attacked by other Iranian-American academics for holding up Western literature as a source of enlightenment for benighted Middle Easterners -- sees the same reductive impulse at work in both universities and cable media outlets like Fox News. "Ideology eliminates paradox and seeks to destroy contradiction and ambiguity," she writes. "While it is generally ruthless to outsiders, it can be consoling when you are in the group that always wears the white hat no matter what. Hatred and ideology, contrary to all appearances, are comforting and safe for those who practice them. They tend to be accompanied by an odious self-righteousness." (And, it must be said, a penchant for hyperbole. One of Nafisi's critics likened her to Lynndie England, the Army reserve soldier who was sentenced to three years in prison for her role in the abuse of prisoners at Abu Ghraib.)

Nevertheless, even her critics' recondite outbursts point to a problem built into Nafisi's idea of the American character. If we're all independent, free to form our own ideas about how to behave and how the world should work, then what holds us together?

Good question. Nafisi wants to be freed from pressures to "talk, teach and write as a woman from Iran, with a particular position on the 'West' and 'the rest,'" freed from the directive that someone like her "could not love Emily Bronte or Herman Melville." To the contrary, she argues: Great fiction actually shows us how to overcome the divisions of race, creed, gender, class and national origin by guiding us to a fuller understanding of our shared humanity. When you look at it in that light, it's not only American literature that has the power to make a nation out of a miscellaneous conglomeration of outcasts, oddballs, exiles and vagabonds. Literature itself, by its very nature, unites us. Nothing could be more American than reading it, and nothing more dangerous than forgetting its power.

Shares