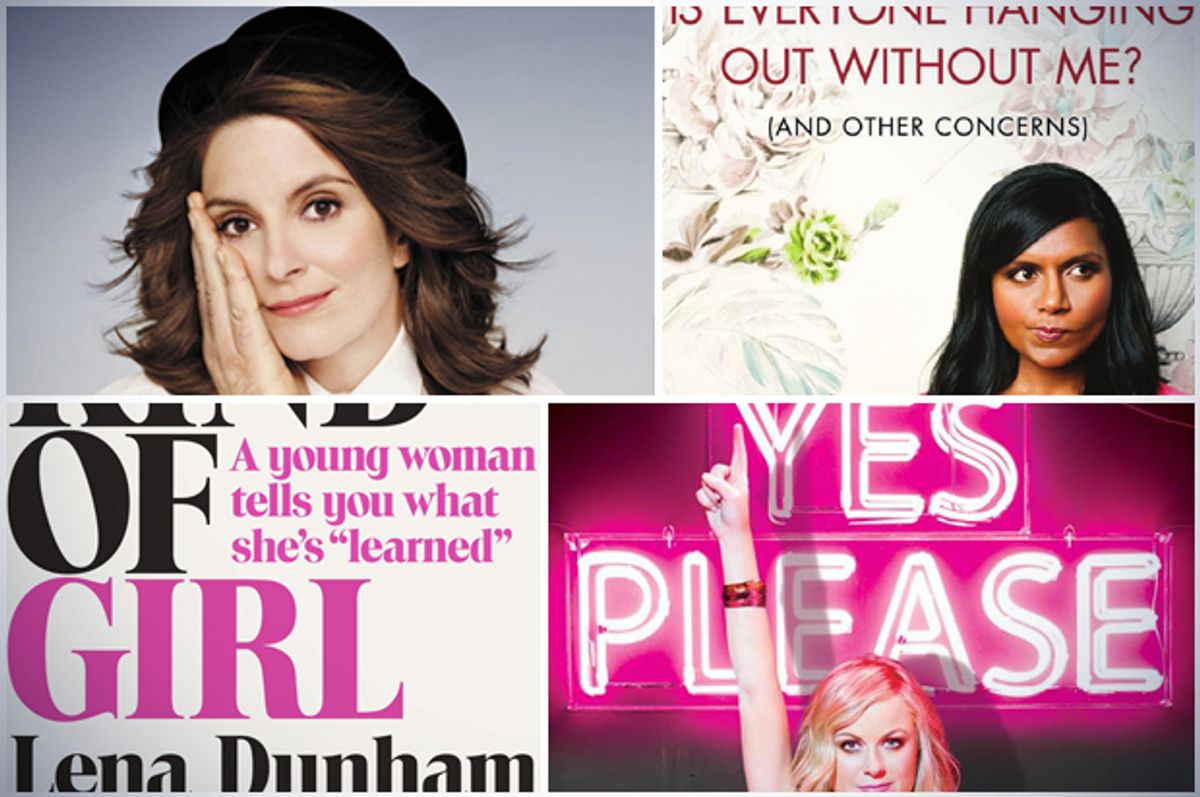

In a New York Times profile a few years ago, Mindy Kaling expressed her irritation at the “media’s tendency to define funny women in relation to one another, as if they’re all competing in a game of musical chairs.” So when I sat down to my pile of celebrity memoirs or pseudo-memoirs--Kaling’s, Fey’s, and Lena Dunham’s, topped by Amy Poehler’s forthcoming contribution to the genre--I was anxious not to put a group of talented women into one narrow bracket. Even calling the female celebrity memoir a genre felt unjust (Kaling’s introduction, a facetious FAQ, includes “Why isn’t this more like Tina Fey’s book?”). In addition, I began the reading on the offense against my worst instincts. If you want to conduct a sociological experience with a sample size of one, pull out a NYT bestseller by a female celebrity on the bus and see how it makes you feel. If you’re me, it might make you feel a little bit “basic,” and that doesn’t make you feel great, either about yourself, or about society.

While I think there was a noble instinct behind my early wariness, I have to laugh at it now that I’ve a) tallied the advances received by each of these women for their work and b) read the books. When the preface to Amy Poehler’s “Yes Please” explicitly reveals that her writing process involved rereading “wonderful books by wonderful women,” including Mindy Kaling’s “Is Everyone Hanging Out Without Me,” Lena Dunham’s “Not That Kind of Girl” and Tina Fey’s “Bossypants,” these books can fairly be considered part of one artistic inheritance. This is an inheritance over which, for better or worse, the ghost of Nora Ephron confidently presides.

Poehler puts this legacy front and center: “While writing this book...I kept a copy of Nora Ephron’s ‘Heartburn’ next to me as a reminder of how to be funny and truthful.” Lena Dunham thanks Ephron, whom she eulogized in The New Yorker, in the credits to her collection of essays. Kaling’s love of Ephron, particularly her romantic comedies, is all over her book, her Twitter, her public interviews. There were almost no reviews of Fey’s “Bossypants” that didn’t evoke Ephron. Since I had never read anything by Nora Ephron, and since she seems to be a critical component of understanding not only these books, but the American female experience, I got some very well-thumbed, obviously cherished titles from the library.

I read “I feel Bad about my Neck”; I read “Heartburn;” I read the prodigious memorials to Ephron that appeared after her death. And I had that weird experience that goes beyond suddenly getting a joke or catchphrase that everyone’s been going around saying, and gets into something fundamental to the self, where you realize that a thing you’ve been doing your whole life is no more a product of your own invention than Christianity, or the unique baby name you were certain you came up with. I hear Ephron in all the female-targeted blogs I read, in the humorous deployment of all-caps comments, in my own writing. My own Ephron was Bridget Jones--who it is now clear traveled from Nora Ephron’s mouth to Helen Fielding’s ears--whose “Diary” I first read when I was 15 and which seemed to represent a female experience so immediately grasped and relatable that it’s actually alarming, when you consider that Bridget Jones herself was meant to be well into her thirties.

There’s a wry, self-deprecating female writerly voice that seems a standard of American popular culture, a voice the comes from Erma Bombeck to Ephron by way of, I don’t know, Erica Jong. According to the gospel of Ephron, one of the central and necessary topics of comedic writing by women is your appearance, something all of these recent authors address with varying degrees of earnestness. Poehler has a chapter called “The Plain Girl vs. the Demon”; Kaling has “When You’re Not Skinny, This is What People Want You to Wear;” Fey has “Remembrances of Being a Little Bit Fat” and “Remembrances of Being Very, Very Skinny”; Dunham has “‘Diet’ Is a Four-Letter Word: How to Remain 10 Lbs. Overweight Eating Only Health Food.” Reading all of these pieces, I thought how one day it would be nice if a book by a famous woman didn’t need to include any extended riffing on appearance and weight, either because it was something the author hadn’t really thought about, or because the market didn’t demand it, or both. But I guess as long as people spend their days writing comments like “Tina Fey is an ugly, pear-shaped, bitchy, overrated troll” and god-knows-what about Lena Dunham, this is what we are going to get. A woman’s appearance is the mute siamese twin she carries around with her whole life, and I suppose it would be awkward not to mention it in a piece of memoiristic writing.

Other rules from Ephron: keep it short, breezy, and include humorous lists. These books are rife with lists (Dunham: “15 Things I’ve Learned from my Mother”; Kaling: “Best Friends Rights and Responsibilities”; Poehler: “My World-Famous Sex Advice”; Fey: “The Secrets of Mommy’s Beauty”). Don’t get me wrong--I chortled on the bus over all of these lists, in Ephron’s work and all the others. And truly, there is something eternally comforting in reading about the gnarly skin on someone’s feet, or their disgusting purse. Ephron helped to usher the humanity of women into the mainstream, not only the maintenance they perform on themselves, but the things they deal with as lovers and parents and employees. I have written about the need for pointed, humane writing on women’s issues, on seeing the value of the personal as a topic for writing and reading consumption, particular in fiction. But what all of these books seemed to have in common, and what they take from Ephron, is that they are about serious women who are expressing themselves in sometimes unserious ways.

Let me be very clear: I don’t think that comedy is unserious. It’s an art form, and all of these women are artists; comedic writing is part of their craft. And in every case, the best and most interesting parts of these books are those parts that really address these women’s work as artists. I loved reading about their respective artistic processes and the hard work they have done--the editorial decisions they made at their jobs, how they got their jobs, the people they’ve worked with, the jokes they like and why, the way they were, in Poehler and Fey’s cases, working insane hours with buns in the oven and/or babies at home. (Interestingly, both Fey and Poehler go out of their respective ways to downplay and/or appease on this front--Fey’s book includes a chart that compares the amount of stress involved in writing for “SNL” and “30 Rock” as much less than that of “coal mining,” “active military service,” “managing a Chili’s on a Friday night,” and “Business Guys.” Poehler begins a chapter saying, “I had no plans of being a full-time stay-at-home mother. This is not to say I think being a stay-at-home mother is not a job. It certainly is. It’s just not for me.”) I went and saw Lena Dunham’s book appearance in San Francisco, and what fascinated me was not the somewhat meandering piece on not-being-a-lesbian she read from her book--one of the weaker essays in the collection, in fact--but the Q&A, which featured her passing mention of the shot composition and color sensibility she inherited from her mother, and how she uses it in her work.

A retrospective of Ephron the Paris Review (by a man, it’s worth noting) lamented Ephron’s swoops between the sublime art and “sub-bimbo daffiness,” and pointed to the things left unexpressed in her work: In 2006, he wrote, “Ephron said that romantic comedies were ‘almost all I’ve been able to get made. I’ve written other things, sad scripts that are on the shelf that are unbelievably serious, hard-hitting political things.’”

Even though comedy is best when it deals with the darkest topics, there is something about the deployment of jokes that can also be obfuscating, even mitigating. In Poehler’s book, as in Fey’s and Kaling’s, there is a dual say-everything quality and reticence, like, I’m going to give you my embarrassing childhood photos and tell you about my gross feet, but don’t ask me about my divorce, or my early childhood traumas. Dunham’s project, which stylistically owes the most to Ephron as an essayist, seems to be fumbling more toward revelation, although she uses the obscuring comedic syntax of Ephron, sometimes with great success (“I have uttered the words ‘I love you’ to precisely four men, not including my father, uncle, and assorted platonic neurotics I go to the movies with.”) Her essay about a college rape is zinger-free, and her writing about sex generally would have been out of place in the other books in my pile.

But even so, humor creates somewhat of an oblique line of attack for addressing the real issues that face women, whether in regard to their sex lives, their home lives, or their work lives. Dunham’s chapter on “Diet,” with diary entries like “a positive goal would be to be 139 pounds by the November 12th premiere of Tiny Furniture” describes an obsessive monitoring of her eating that many women will recognize as being right on that familiar knife-edge of disordered thinking about food. But then this is followed by a chapter on public nudity that dismisses all back-handed plaudits of “bravery” which are firmly tied to people’s perceptions of her body. “It’s not brave to do something that doesn’t scare you. I’d be brave to...argue a case in the United States Supreme Court or to go to a CrossFit gym.”

I saw Lena Dunham with a friend and after the event we talked about the genre of celebrity “lady books.” My friend said that behind Fey’s book, though, she felt more of the gentle prodding of an agent who said, “It’s time to write a book.” There is a pastiche quality to all of these books, but particularly to Fey, Kaling, and Poehler’s--the lists, the childhood photos, the excerpted emails and notes--that hints at a large market forces and the need to make these books all things to all people: people who want funny jokes, people who want to see how the TV sausage gets made, people who want insights into the adolescent yearnings of their pop culture heroes, people who go to Barnes & Noble to buy a latte and cruise the fun-stuff section at the front of the store. It’s a testament to the talents of these women are that they can basically succeed at reaching so many types of readers, but it’s also telling that they (and their editors) feel pressure to make these books work on so many levels.

Were these books less alike, I would never lump them together this way. But the resemblance is at some moment truly uncanny. I’m torn on two fronts: I think about 14-year-old-girls, and how important it is for them to read things by accomplished women, things that let them know that even the most charmed people have moments of feeling ugly and worthless and embarrassed. There is an advice component to all of these books that is surely useful for any professional woman, even when some of it seems not-in-keeping with current feminist thought (Fey’s advice about keeping your head down and working around your sexist boss has a collaborationist ring, although I do like the moment where she spoofs a Hopkins-educated doctor speaking only in sentences ending with question marks). And I’m aware that I should be celebrating the fact that women are being paid millions of dollars for books that include writing about typically female experiences of childbirth, motherhood, and body image anxiety--topics that are seen as parochial precisely because they are perceived to be women’s, rather than universal, issues.

But it still seems odd to me that some of the things that delighted and comforted 15-year-old me about Bridget Jones in the late 1990s (because, yes, Bridget Jones’s Diary was published almost twenty years ago)--her food diaries, her struggles not to chug cigarettes and chocolate, her constant humiliations in front of boys she liked, things that have been popping up in a slightly more polished form in Ephron’s writing over the decades--are still front and center in the oeuvre of our newest batch of accomplished women.

Shares