For such a larger-than-life figure, Edwin Edwards’ campaign headquarters is surprisingly low-key. Nestled away in a tidy, middle-class subdivision near Baton Rouge’s Mid City district, the Edwards for Congress headquarters looks just like any of the other white-walled townhouses in the area, one frequented by soccer moms and semi-prosperous young professionals.

A walk through the building’s solid wooden door, though, proves that things inside are very much different from how they initially appear. Only days away from the Nov. 4 election for Louisiana’s 6th Congressional District, the building is a hive of activity. Four young badge-wearing Edwards supporters cheerfully sit at desks taking and making calls on behalf of the candidate; phones ring, directions are issued, people rush in and out of the room. Edwards’ wife, Trina, a tenacious woman 51 years his junior, scurries about with messages to and from her husband. And down a corridor, away from the commotion and sitting behind a large wooden desk is the man himself, the candidate, the crook, the comeback kid. “Hi,” he says with an outstretched hand and an emotionless face. “I’m Edwin Edwards.”

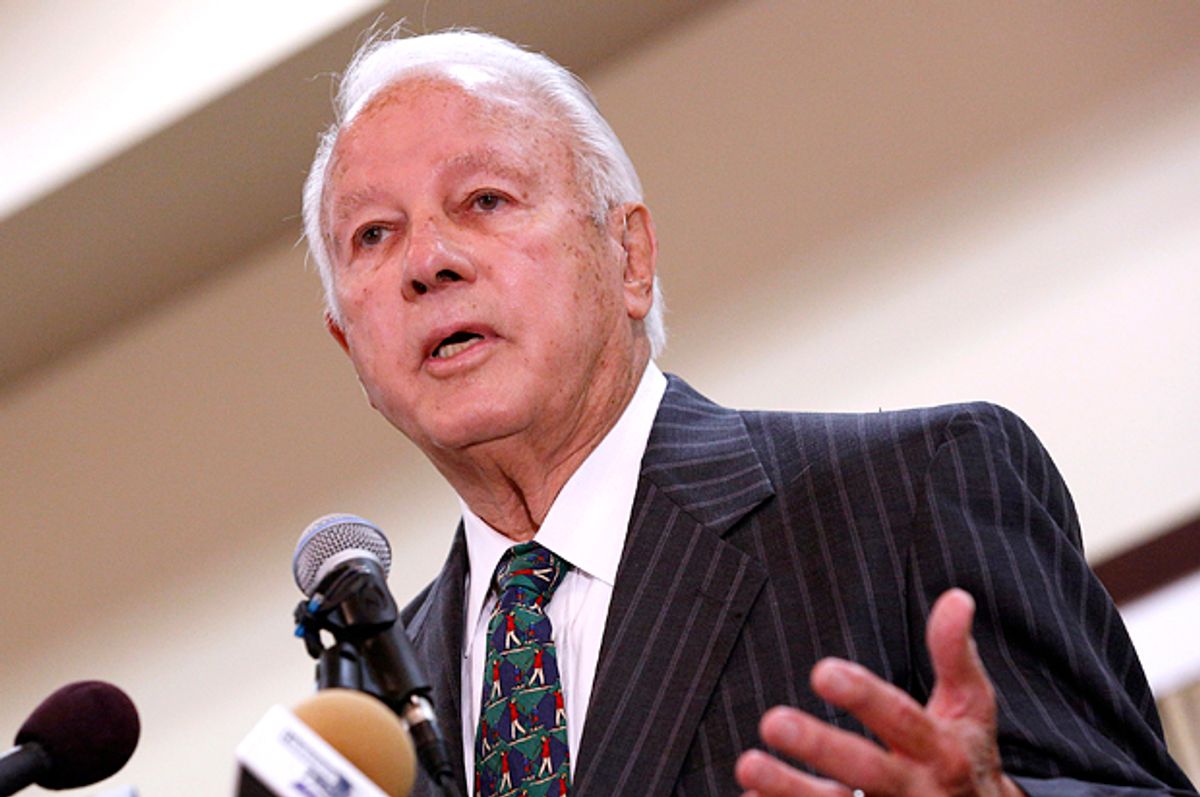

In a state with a long history of outsize political characters, Edwards is one of the giants. A former U.S. congressman and, between 1972 and 1996, four-time governor of Louisiana, Edwards has formed a reputation as a skilled politician with dubious morals and a razor-sharp wit. He’s one of a few former politicians whose name is instantly recognizable to Louisianans of all ages, due to his long history in politics and larger-than-life notoriety. Long dogged by allegations of corruption, Edwards’ career looked to be over in 2001 when he was finally found guilty of racketeering charges and sentenced to 10 years in federal prison.

It wasn’t. Following his 2011 release he jumped straight back into the public eye, marrying former prison pen pal Trina Grimes Scott – who was born during Edwards’ second term as governor – and taking part in a reality television series titled "The Governor’s Wife." “I’m only as old as the woman I feel,” he quipped at the time. In March 2014, after rumors had been swirling for several months, he formally announced a run for Congress in Louisiana’s 6th District. At the astonishing age of 86, the governor was back.

Edwards, canny political operator that he is, isn’t one to be drawn into a battle he’s completely certain to lose. Although Louisiana’s 6th District is staunchly Republican – a result of the contentious practice of gerrymandering, which nobody seems to like but nobody tries very hard to stop, either – early polls put Edwards well ahead of his Republican challengers when it came to November’s open primary. One poll in June put him at 32 percent, double that of his two nearest rivals, while a July poll gave him 35 percent, well ahead of the 13 percent obtained by conservative businessman Paul Dietzel. Strong numbers for the only Democrat in the race.

The primary is one thing; the runoff is quite another. If nobody gains 50 percent of the vote the election will come down to a Dec. 6 runoff between the primary’s top two finishers. Edwards will almost certainly be one, but here his numbers are lower; most polls show him trailing by around 15 points.

“It will be touch and go,” he admits. “But I’ll just have to face the opponent I have in the runoff, and hope in the debates and other methods I can get my message across. I feel confident it’ll be all right, although I wouldn’t tell you it’s an absolute cinch. I think it’s an absolute cinch I’ll get in the runoff because I’m the leading candidate [in the primary]. After that it’ll be close, but I’m up for it.”

Edwards is no stranger to comebacks. His most famous came in 1991 where, weakened by corruption allegations and a coming off a rare loss in the 1987 governor race, he ran against former KKK grand wizard and neo-Nazi David Duke. Bumper stickers reading “Vote for the Lizard, not the Wizard” and “Vote for the crook” began circulating as Edwards embraced his dubious standing in the public eye as he went on the offensive. At the end of the day, and to nearly everybody’s relief, Edwards walloped Duke by nearly 400,000 votes. “We do have one thing in common,” he said at the time. “We are both wizards under the sheets.”

He has also never shied away from his public reputation as a somewhat seedy politician. “To do opposition research on someone like Edwards would be a complete waste of time and money,” Garret Graves, one of his challengers in this year’s election, told the Wall Street Journal in early October. “He admits to everything.” Still, even Edwards himself has expressed surprise at the level of support he received after his recent prison stint. For a while, he says, another run for political office seemed beyond even him.

“I never even considered it,” he says, “because even I was not aware of how understanding and sympathetic the people of Louisiana would be. But after I got out I went to 53 or 54 cities and towns and villages selling books and making speeches, and I marveled at the reception and the encouragement I got from people. And I just became convinced for many reasons that people in this state want me in office because they know I can get things done. They know I answer the phone, I’m here when things happen, I make things work. I may have a strange way of doing it, but I do make things work.”

For all his faults, Edwards was an organized and highly skilled governor. “He’s popular because he actually did a lot of work,” Edwards’ biographer Leo Honeycutt says. “He did a lot of personal things for people, which is kind of what a governor’s supposed to do.

“Everywhere we go, somebody comes up to Edwards and they say, ‘You got my son into the military, you got my son out of the military. You got my son into medical school, you got my daughter into college, you got my aunt into a hospital.’ I mean, it just goes on and on and on. Even when we were in prison people would come up to him and say, ‘Governor, you really helped my family 18 years ago.’

“He’s a huge delegator. He’s one of the most efficient administrators of government this state has ever had.” Edwards, Honeycutt points out, was one of the last governors to maintain a consistently balanced budget.

He’s also something of a populist. Having had a long-standing reputation as working for minority groups and the poor, he spent much of his time in prison working on behalf of some of the most disadvantaged of all.

“Prison made me more sensitive to the needs of people less advantaged than we are,” he says. “It made me more aware of the fact that some people have no friends, no family … so I did what I could to help my fellow prisoners. People couldn’t read or write, so I did basic legal work for them.

“I made myself busy because I thought I wasn’t going to waste my time and wail and cry and feel sorry for myself. I just made myself useful.”

It’s his combination of charm, political ability and concern for the underrepresented that goes a long way toward explaining why he’s still so popular, and not just with older voters who have supported him in the past. Indeed, Edwards had already been involved in high-level politics for 20 years by the time many of his current fans were born. “My dad used to tell me stories about ‘the legendary Edwin Edwards’ when I was a kid,” says one of the new generation of supporters, 25-year-old Edwards campaign intern Joshua Fini. “He’s always had such a large reputation for helping the underprivileged and the poor. He commands an amount of loyalty that I’ve never really seen before. He’s one of those polarizing candidates, but people who do adore him treat him like he’s the last hope we have. It’s almost unquestionable. People say, you know, why would we vote for anyone else?”

It’s Fini, along with Edwards’ wife, Trina, and a couple of campaign advisers, who flanks a sharply dressed Edwards as he arrives at a candidates debate in Baton Rouge on a stiflingly hot late October morning. Just like Honeycutt recounted, before the Edwards team even makes it through the door it’s stopped by an older man who thanks Edwards for a favor given to a friend years, probably decades, ago. “He told me that if I see you to say hi,” he says, with a grateful look. Edwards, expressionless as ever, shakes the man’s hand before heading inside.

The debate, hosted by Leaders With Vision – an unaffiliated offshoot of the League of Women Voters – proves to be a typical political luncheon, with a who’s-who of local political figures in the audience and a panel of four journalists asking the candidates mostly standard, occasionally left-field, questions. Once everyone sits down and the debate begins it quickly becomes clear who the star is. Sitting at the end of the table and looking decidedly serene, it’s obvious that Edwards is in his element.

While it would be unfair to say Edwards runs rings around his competitors – possibly save his potential runoff rival Paul Dietzel who, on this occasion at least, frequently appears flustered and somewhat out of his depth – he appears to be the most at-ease person on the podium. Whenever he stands up to speak he gains the fixed attention of the entire audience. He’s also the only candidate to receive applause after a majority of his answers, despite organizers' attempting to ban such outbursts until the end of the debate. His wit, sharp as ever, is on full display; when asked whom he would support in the race other than himself, he demurs. “I wouldn’t want to hurt anybody’s chances by naming them,” he says, to widespread laughter. He trots out a couple of his favorite one-liners, too, noting that smoking marijuana is “one of the few sins I’ve never been accused of,” and claiming that if he was elected to Congress “at least I can’t make it any worse.” After one comment sends the room into uproarious laughter, Leo Honeycutt, sitting in the audience, leans across the table. “The Rodney Dangerfield of politics,” he whispers, with a shake of the head and a smile.

When the debate finishes Edwards doesn’t stick around, spirited out by his team for, presumably, another engagement. It’s been classic Edwards: assured, confident and charming. It’s also very easy to forget that he’s not far off 90 years old. “We all have something to strive for,” someone says in awe. “I don’t think I’ll even make it to 87, let alone be like that.” Even for his detractors in the audience – and there are many, given the number of old-time journalists and Republican Party members in attendance – it’s clear that he still commands an awful lot of respect. Maybe even more than ever.

Whether he’ll win the runoff on Dec. 6 is up in the air. He’s fighting an uphill battle; Honeycutt says it’s the toughest race of Edwards’ career and even the candidate himself acknowledges it won’t be easy. “I haven’t thought about [losing] because not winning is not in my history, nor is it in my thoughts, nor is it even in the possibilities. Even though,” he adds, cracking a slight smile, “it is possible.” Carl Redman, former editor of Baton Rouge daily the Advocate, is more blunt, noting that Democrats can only count on around 20 percent support in the 6th District. “He’ll get all those, but [an Edwards victory is] almost outside the realm of possibility,” he says.

Then he pauses. “But,” he says with a knowing smile, “don’t count him out.”

Shares