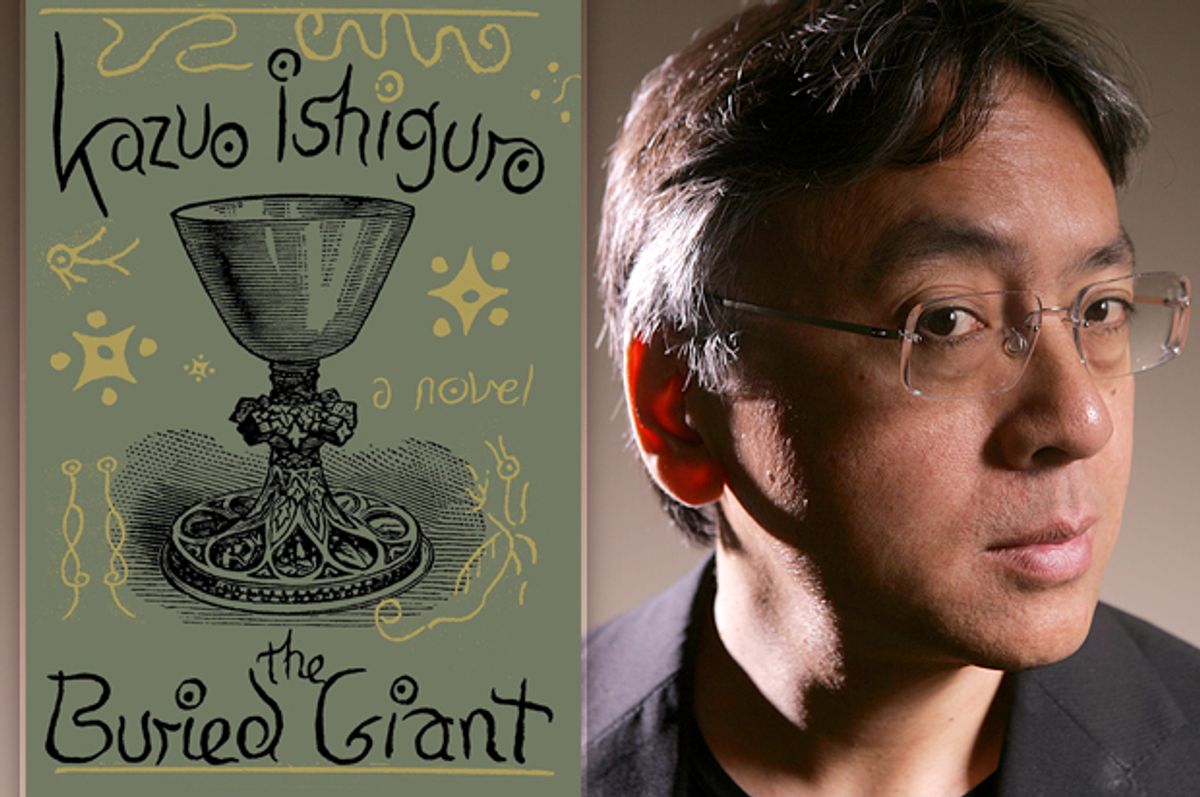

To understand why Kazuo Ishiguro’s ambitious new novel, “The Buried Giant,” doesn’t quite work, it helps to understand what it’s trying to do. Unlike his two best-known works, “The Remains of the Day” and “Never Let Me Go,” this book takes place not in a recognizably modern world, but in a quasi-historical Britain, a rugged, harsh landscape where villagers dig their primitive homes out of hillsides and regard a nighttime candle as a luxury. Set sometime in the Dark Ages, after the withdrawal of the Roman Empire from the island and before the rise of the seven kingdoms known as the Anglo-Saxon heptarchy, “The Buried Giant” is historical in the way that history is preserved by people who cannot write: as legend, story, rumor and myth.

Despite what you might read elsewhere, however, this is not a fantasy novel. It has very little of substance in common with “Game of Thrones” or “The Lord of the Rings.” Yes, creatures like ogres and dragons stalk its landscapes and some of the characters knew King Arthur personally, but “fantasy” is a contemporary genre that uses the form of the novel to deal with the material of pre-novelistic storytelling. “The Buried Giant” reverses that formula, using the structure of a medieval romance to explore the moral and psychological themes we’re used to seeing addressed by the realistic novel. This may seem like an obscure and technical distinction, but it makes all the difference between savoring the riches of this peculiar book and being blindly flummoxed by what it lacks.

The central characters are an aging couple, Axl and Beatrice, who live in a warren-like settlement, “on the edge of a vast bog, in the shadow of some jagged hills.” Their neighbors patronize and dominate them, and the pair, utterly devoted to each other, decide to pursue a much-postponed plan to visit their son in another village. They don’t remember where the village is or why they haven’t seen their son in years, but this isn’t so unusual. Everybody’s memory is fragmented and ephemeral, and Axl’s is actually better than most; he notices that the local medicine woman has simply disappeared and that most of his neighbors don’t seem to recall that she ever existed. (Missing women, presumably abducted, become a theme in the novel, although who exactly has taken them remains unclear.)

The pair set out and in their travels learn that these problems are pervasive; eventually they discover that the breath of an ancient she-dragon living up on a mountain has covered the landscape in an insidious mist that robs both Britons (the Celtic natives) and Saxons (Germanic newcomers) of their memories. This Beatrice finds unbearable. She and Axl know they love each other, but what does that really mean if they can’t remember the life they’ve shared? Along the way they meet a wandering Saxon warrior, a fierce boy afflicted with a mysterious animal bite, many superstitious villagers, an abbey full of dodgy monks, and Gawain, the nephew of King Arthur. His uncle long dead, Gawain has become an aged knight roaming the countryside in a protracted search for the she-dragon, like a less-comic version of Sir Pellinore in T.H. White’s “The Once and Future King.”

Ishiguro has described the Middle English romance “Sir Gawain and the Green Knight” (by an unknown author) as a major inspiration for “The Buried Giant.” That poem itself was a kind of historical fiction, written in the 14th century, 900 years after the events it purports to describe. Ishiguro’s Arthur is closer to the historical one (even if his actual existence is the subject of much debate): a tribal chieftain of the Britons who for a while managed to impose peace with the Saxons. The author of “Sir Gawain” lived in an age of turreted palaces, jousting tournaments and ladies with brilliant scarves fluttering from their tall pointed hats — basically, what most of us associate with Arthurian legends and Camelot. Ishiguro’s Arthurians, like the actual denizens of the Dark Ages, could count themselves rich if they lived in a house with more than one room.

The critic Northrop Frye described the romance as “the mythos of summer.” Its characters, typically questing knights, are in the prime of life and determined to prove themselves. Like superheroes, their modern-day equivalent, they charge through a series of adventures in a landscape spangled with supernatural marvels and harried by wicked enchanters (AKA supervillains). Although human, these heroes often possess special powers or magical weapons. Romance is also a form in which, Frye wrote, “subtlety and complexity are not much favored. Characters tend to be either for or against the quest.” While “The Buried Giant” has some of the furniture of a romance — including the tendency of characters to speak in a deliberate, declamatory fashion that sounds stilted to ears accustomed to modern diction — Ishiguro has bent these tropes to entirely alien themes. The characters are (mostly) old, and what they search for is (mostly) locked up inside their own heads. Killing the dragon will not win anyone a princess bride, but it will literally free the characters to know the lives they have already led.

It’s a weird and daring project, this hybrid of modern psychology and medieval storytelling devices. In romances, as is often the case in contemporary fantasy novels, the setting and its marvels manifest elements of the main characters’ inner lives. Instead of being divided within himself — such as Hamlet, an essentially modern character — the hero of a chivalric romance will often accept orders from a virtuous authority figure and fend off the blandishments of an evil tempter, like a cartoon character with a little angel on one shoulder and a devil on the other. Ishiguro’s characters, on the other hand, are preoccupied with modern moral dilemmas — Can good ends justify evil deeds? Are self-knowledge and happiness compatible? What do we owe the past? — while moving through a world ruled by the romance’s archetypal figures of fairy tale and myth.

As I mentioned above, this fusion doesn’t always work, but when it does the results are fascinating and moving. Throughout the story, as Axl begins to recall a past that he fears will drive him and Beatrice apart, the old lovers discuss the ferryman they meet early in their adventures. This man takes people to a beautiful island, but most of them have to travel alone. Every so often, a couple responds to his questions about their past in such a way that they are allowed to travel together. Beatrice wants herself and Axl to be one such couple, but how can they answer the ferryman’s questions adequately when they don’t have any memories to share?

Much of “The Buried Giant” has to do with the communal cost of memory and grievance, whether it’s possible for people to live together in peace without a willful forgetting of each other’s transgressions. In that, despite its British setting, the novel feels like the secret twin of Haruki Murakami’s “Wind-Up Bird Chronicle,” with its storytime language and wary circling of Japanese wartime atrocities. At one point, early on, Axl and Beatrice cross an ill-favored plain where the buried giant of the title, a huge earthen mound, is avoided by every prudent traveler. Revelations later in the story suggest that something else might be buried there instead and that it won’t lie covered up for long. But these are the least effective passages in the novel, and when Ishiguro presses on such themes, the book can feel aimless and atomized.

The true backbone of “The Buried Giant” is the love between Axl and Beatrice: very tender, gentle and simple, but in the end capable of invoking the emotional resonance of Ishiguro’s best fiction. If much of the rest of the novel registers as an intriguing experiment imperfectly realized, he shows he still has the ability to bring home moments of serene and transcendent sorrow mixed with an inexplicable joy.

Shares