Like many, many people who were lucky enough to call Lisa Bonchek Adams a friend, I never met her. But like thousands of readers who followed her story, I knew her. Because Lisa Bonchek Adams had the courage to be known.

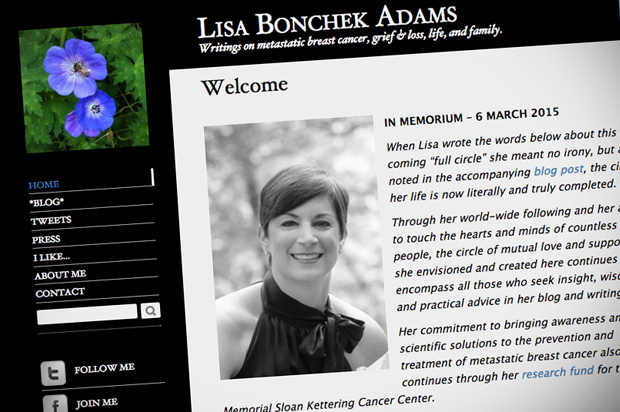

Over the past several years, the Connecticut mother of three had developed a devoted following for her writing about her breast cancer experience – on her blog, on Facebook and via her conversational and deeply engaged Twitter presence. When she was rediagnosed – at Stage 4 – in 2012, her condition ignited in her a deeper passion to demystify the cancer experience, and to be an active voice for honesty in a world of insultingly sexualized and infantilizing breast cancer cheerleading. She was an enemy of ignorance and bright siding. Or as she put it, “If it were as easy to defeat cancer as mindset, people would not die of it by the thousands every day.”

I first interviewed Lisa two years ago, when I was wrestling my own then-recent experience of Stage 4 melanoma. I had found inspiration and validation in her ferocious refusal to become invisible in the face of a form of cancer for which there is no known cure – and certainly not to do so for the sake of some comforting, pink-ribboned fiction. She told me then, “I don’t need to be told to fight the good fight to beat it or the key is to just stay strong or that it’s mind over matter. You force me to assert my knowledge, insist upon my diagnosis, explain the desperate nature of my disease, spend my time defending my sentence.”

Of her writing she said, “What I try to focus on are the emotions that accompany these hardships: fear, anger, despair, hope, grief, love.” And she did that with exuberance and grace. Yet for her frank and frequent discussion of metastatic breast cancer, her own in particular, Lisa found herself last year the subject of a one-two punch of concern trolling over the way in which Lisa chose to document her experience, first from Emma Keller in the Guardian, and her husband, Bill Keller, in the New York Times. “Is there such a thing as TMI? Are her tweets a grim equivalent of deathbed selfies, one step further than funeral selfies?” asked Mrs. Keller, whose morbid Op-Ed so mortified readers the Guardian soon deleted it. Her husband, meanwhile, followed up with a Times piece that suggested writers like Lisa “shouldn’t be unduly praised.” Yet even in the face of a public questioning of her behavior from two very high-profile platforms, even when she was regularly approached online by purveyors of misinformation and flat-out quackery, she was classy. Even in the face of occasional full-on trolls, she was firm but polite.

She was so gracious. I can’t think of a single time I communicated with her, in public or in private, that she didn’t come back promptly with a thoughtful response. And if you look across her public timeline – or the outpouring of profound sorrow and respect her death has inspired across social media — you’ll see, more than updates about her health or even reminders about what living with late stage cancer is really like, her devoted engagement with others. Her sincere encouragement of other people living with breast cancer. Her sympathy for those who’ve experienced loss. Her constant and generous willingness to inform and educate and wrest breast cancer away from its infuriating, dangerously cute image and to illuminate it as it truly is. She made a community, and her legacy is that it continues.

In a post nearly three years ago, Lisa commanded, “When I die don’t say I ‘fought a battle.’ Or ‘lost a battle.’ Or ‘succumbed.’ Don’t make it sound like I didn’t try hard enough, or have the right attitude, or that I simply gave up … When I die tell the world what happened. Plain and simple. No euphemisms, no flowery language, no metaphors.” It’s great advice. And I hope more people now get to consider it and practice it. To have a disease, to die of a disease, these are not shameful things and they are not failures. Lisa Bonchek Adams was a wife, mother, friend, writer and advocate. She died on March 6 of metastatic breast cancer. She was 45. And she is missed.