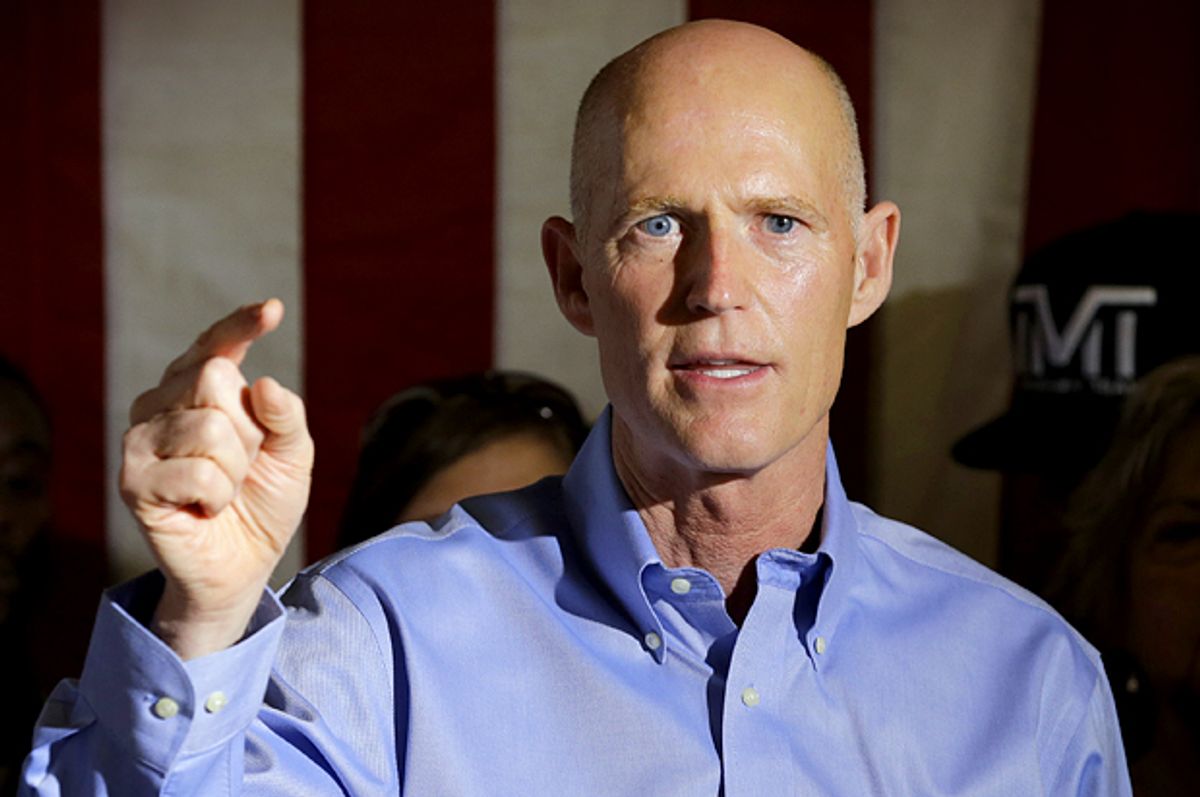

Rick Scott has never made a secret of his distaste for talk of climate change. But the full extent of his willful denial was revealed earlier this week, when former employees of the Florida Department of Environmental Protection accused the governor of banning the terms "climate change" and "global warming." While the waves of Twitter ridicule have come and mostly gone — how does Scott have the audacity to think he can wish a planet-size problem away? — the wide-ranging, terrifying implications of his alleged policy are still continuing to emerge.

Since the Florida Center for Investigative Reporting first published its exposé of the state's unwritten policy, even more whistle-blowers have come forward, alleging that the ban extends beyond the DEP to the Departments of Health and Transportation. Some say they were told flat-out never to use the words in official communications; others that they were forced to delete them from their scientific research articles.

The extreme, Orwellian nature of the ban certainly struck a nerve. It's rare, after all, to see climate denial take such a literal form. The news also reveals just how thoroughly Florida's leader has rejected science -- and how far the state is falling behind in preparing for the threats already lapping at its shores.

Scott, for his part, denied that a ban exists -- an assertion belied by a reported "steep decline" in the terms' use in DEP documents since he took office. But in the course of defending himself, the governor made clear that even if his officials aren't forbidden from speaking the words themselves, his administration is nonetheless hell-bent on avoiding the issue. As in the past, Scott repeatedly dodged questions about whether he accepts the scientific consensus on man-made climate change, refusing to say whether he sees it as a threat and, most pertinently, whether the DEP is in any way preparing for it.

“I’m into solutions, and that’s what we’re going to continue to do,” Scott insisted Monday, apparently under the impression that talking about climate change is somehow a distraction from that goal.

Last year, a group of Florida scientists tried their hardest to explain the science to Scott and they in fact came back to him a few months later with an itemized list of "real, effective, timely, market-based and cost-effective solutions" to climate-related problems facing Florida. These solutions ranged from things that could help mitigate climate change as a whole, such as increasing energy efficiency and promoting renewable energy, to local actions like planning for sea level rise and supporting climate education in schools -- none of which Scott mentioned in his defense of the state's policies on Monday.

Those who have been watching say the governor's actions speak for themselves.

"Under Rick Scott, the DEP has had the crap kicked out of it," Jeff Ruch, the executive director of the nonprofit Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility (PEER), told Salon. Under the Scott administration, funding for the agency has declined, as has enforcement of anti-pollution laws; according to a staff editorial in the Tampa Bay Times, the governor "triggered a brain drain among regulators, sided with polluters and developers over public health...and stalled any serious attempt to address water quality, land conservation or growth management."

"It's almost like the failure to address climate change is the least of their worries," said Ruch.

But without acknowledging the elephant in the room, scientists studying climate change in Florida say, the necessary work of protecting the state and preparing it for future threats is going to be difficult, if not impossible.

"The governor can set the tone for the entire state, and he has the power to initiate planning activities," Chris Langdon, who chairs the Department of Marine Biology and Ecology at the University of Miami, told Salon. "When the officials deny that it's even happening, it just paralyzes the entire process."

For researchers employed by the government, of course, the ban impacts their ability to do research at all. "For the most part, I think agency scientists just trying to keep doing what they're doing and not get killed for it," said Ruch. If the government wants to interfere with their work, he explained, whether by softening their conclusions or removing the words "climate change," they have little legal recourse. Government employees who speak out don't fall neatly under a whistle-blower model, which protects those who disclose either a violation of the law, gross mismanagement or imminent danger to public health and safety. (Ignoring climate change could arguably fit under that third requirement, but it'd be a difficult case to make.) Meanwhile, so-called scientific integrity rules, which aim to prevent officials from altering scientific research for "non-science" (read: political) reasons, are unevenly applied at the state level.

For scientists working outside the DEP, of course, the government can't interfere with their work -- but they don't have to pay attention to it, either.

"We do research and we're trying to tell people what's going to happen," said Langdon, who studies the impact of climate change on Florida's coral reefs, "but no one's acting on it."

Ben Kirtman, a professor of atmospheric sciences at the University of Miami who was among those who attempted last year to convince Scott of the urgency to act, described what he calls the "nuisance factor" in dealing with the state government. "Any time I go to a science meeting and the state agency representatives are there, we always have to dance around the climate change problem," he said. "That happens all the time."

But the policy really starts to cause trouble when it comes to pragmatic plans for adapting to the effects of climate change that are already being felt, Kirtman said: "It creates a perception problem that could make it difficult for municipalities to actually deal with the realities on the ground." In South Florida, for example, it can be hard for local officials to convince the public that they need to raise taxes to fund the infrastructure projects, like installing pump stations or raising roads, that are needed to address floods caused by rising sea levels -- a focus of Kirtman's research -- when the message coming from the top is that there's no reason to believe the problem is real.

The ultimate irony, said Kirtman, is that South Florida can be seen as the "epicenter" of climate change, at least within the continental U.S. "At first, that's sort of a negative, right? We're at the leading edge of the problem," he said. But viewed another way, he added, it can be seen as an opportunity: As the first to be confronted with warming's impacts, the state's in a position to be a trailblazer in developing strategies and technologies needed to address them.

"I think we're making an economic mistake in not saying, 'Yes, we're going to deal with climate change, because it's a real problem here, and we're going to lead the nation, if not the world, in how to adapt," Kirtman said.

Instead, Florida has chosen a path that could lead it to becoming the first state taken down by a force that, officially, never even existed.

Shares