Nazanin Boniadi is a television actress with a few huge hits in her résumé: “How I Met Your Mother,” “Scandal,” and most famously, “Homeland,” where she played Fara, an Iranian-American CIA agent who was also a practicing Muslim. In 2013 we wrote that “Homeland”’s treatment of her character was a significant part of the show’s general difficulty with not demonizing Islam, and after Fara debuted, Boniadi went on to play a Muslim terrorist (!) in “Scandal” before being murdered at the end of the third season.

Earlier that year, Interview Magazine did a short Q&A with Boniadi, mostly for the opportunity to run a few sultry photographs of her (hard to blame them: Boniadi is stunning). The interviewer asks Boniadi about her preparations for playing a Muslim character, her interests in international affairs, and how the Iranian revolution affected her family. Boniadi responds with some pretty basic actor-platitudes: “three-dimensional,” “documentaries,” “organizations.” Like many young women, she is passionate about justice and human rights; she is an activist for Amnesty International. She tells the magazine things like: “I believe a lot of artists become activists because we rely on and value the freedom of expression and so we want to protect it.”

Boniadi might be good at depicting Muslim characters, but she’s not Muslim. She was a Scientologist for most of her life, by her own admission; it is a period of her life she now refuses to discuss. And if what writers about the Church of Scientology have posited about Boniadi’s time in the church is true—if even a fraction of it is true—Boniadi could be coming to her sense of justice not from her ties to Iran, but from the manipulation she dealt with at the hands of Scientology. The story is so outsize and absurd as to sound like science fiction—but then again, literal science fiction comprises the backbone of Scientology’s belief system.

As Maureen Orth reported in 2012 in a cover story for Vanity Fair, Boniadi, as a young medical student, was selected and made over by the church before being flown to New York for a private audience with Tom Cruise, who was at the time looking for a girlfriend. As Orth's story reports, the Church had interfered with Cruise’s marriage to Nicole Kidman to the point of its dissolution; now, they were looking for a Scientology-friendly replacement, so as to protect Cruise’s involvement in the church (a partnership that brings Scientology legitimacy, notoriety, and cold hard cash). Boniadi and Cruise dated for a month or two before the relationship went south, and that’s when the story gets weirder. It was bad enough that the church had essentially pimped Boniadi out for an elite congregant; but after she failed to keep the relationship going, she was reportedly punished with menial labor, like being made to scrub toilets with a toothbrush.

The Interview interview, through that lens, reads like an attempt for Boniadi to reclaim her own narrative—and to distance herself from the church as much as possible. It has that effect, to be frank. Partly because the Vanity Fair story is so outlandish, it’s hard to believe; and partly because Boniadi then and Boniadi now sound like two completely different people.

That seems to be kind of what Scientology does to you, though.

*

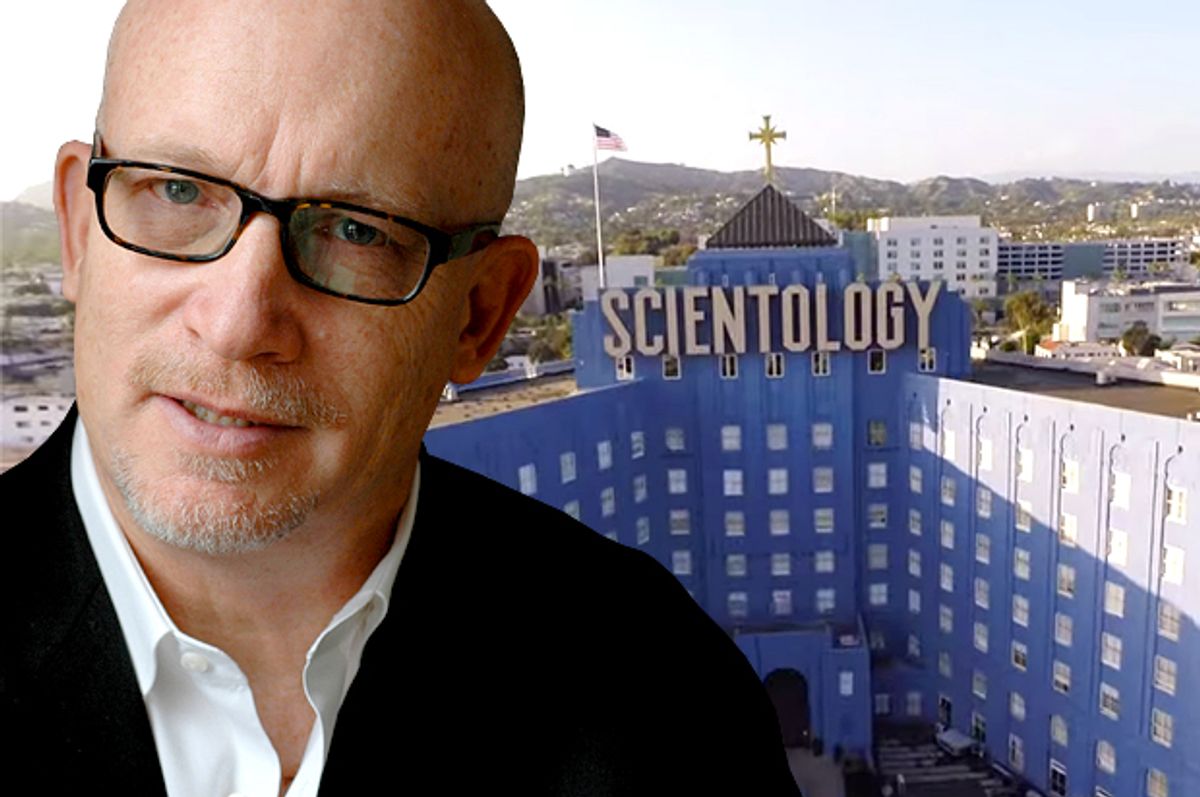

“Going Clear: Scientology And The Prison Of Belief” is not the first attempt to tell the real story of L. Ron Hubbard’s church. The documentary follows not just Orth’s Vanity Fair story and multiple exposés in the Tampa Bay Times (formerly the St. Petersburg Times) but also the book of the same name, by Pulitzer Prize-winner Lawrence Wright.

But the HBO doc may end up being the most wide-reaching. On HBO, the story reaches millions of premium-paying customers in just two hours—more than a book or a cover story could do in that time. And it’s fantastically made—a clearly written, beautifully rendered story of misdirected energy, bad science, megalomaniacs, and the many good intentions on the way to hell. The two hours of the documentary are gripping, as each of the documentary’s eight ex-Scientologists share more and more details about their time in the organization. The church has made much of how the film is smearing Scientology, but if anything, the documentary could stand to be more gruesome. “Going Clear” the film is very careful about presenting just the most verifiable, most comprehensible facts—even though Scientology itself often defies comprehension. So, for example, deaths connected to the church are left out, as are potentially confusing details like exactly how and where church members lived within the organization (it seems that churchgoers disappearing for days at a time would not have raised significant alarm).

Still, it’s odd: In many ways, “Going Clear” is a collection of alleged abuses that have been reported on many times in the past; it’s revealing little to no new information on the church. Instead, it’s really an exercise in effective packaging. The focus is less on the human capital lost in service to Scientology and more on its finances. Hubbard managed to work his anti-tax rhetoric into not just his private conversations with fellow believers but also his handwritten scripture of Xenu, the overlord that froze people and sent them into space some 75 million years ago. How did Xenu lure his subjects into the chambers where they were then cryogenically frozen? Oh, by making them come in to pay their taxes.

What’s particularly galling about Scientology is that it lives at the intersection of two billion-dollar industries—the industry of self-serving “religion,” dominated by the church, and the equally self-serving industry of Hollywood. This is the real test of “Going Clear”—not the general public, which seems at least vaguely skeptical of Scientology; not journalists, who have long been critical; not even the government, who would have preferred to collected on those billion dollars in unpaid back taxes. It’s Hollywood, where the church has a significant foothold and continues to draw new members. “Going Clear” hones in on the stories of John Travolta and Tom Cruise, the two most public faces of the church of Scientology, and makes the case for not just why actors like these two might have joined, but then the mechanics through which they ended up staying.

In the years between the first rumors of abuses within the church and “Going Clear,” though, it’s not like either Cruise or Travolta have found themselves out of jobs. Nor have any of the people on this lengthy list, including Elisabeth Moss, Juliette Lewis and Laura Prepon. We have all been living in and contributing to a world where Scientology is normalized, even as mounting evidence suggests that it might routinely destroy people’s lives. There’s far too much money to be made—for Scientologists and Hollywood insiders alike—to be distracted by something as inconvenient as the truth. Unlike the Scientologists, though, we do not have a readily available set of preprogrammed beliefs to assuage our doubts.

*

There’s one particularly sordid tale from the annals of Scientology that sounds ripped from pulp fiction—the story of church president David Miscavige bringing a cadre of 75 or so high-ranking Scientologists to two crappy trailers with bars on the windows in the California desert for the purpose of breaking their collective spirit. Various mostly minor horrors ensued: one man was made to clean the floor with his tongue, another was drenched with water and put under the A/C until his skin turned blue. At one point, drunk with power, Miscavige literally makes them all play musical chairs, saying that whoever loses will be out of the church.

But what caught my attention was what the church members called these two prison-trailers—“The Hole.” In “Scandal,” Shonda Rhimes’ hit show, a shadowy organization with limitless power and ties to the government has its own “The Hole,” except in this case, it’s a literal hole. Otherwise, though, the operatically named “B6-13” and the church of Scientology have a lot in common. Both brainwash their people, and then use them to do bad things against other people, in the name of a higher power; both are run by narcissistic men with delusions of grandeur. Both operate under a blanket of secrecy that evades the reach of the rule of law. Both destroy people—their people, and other people, too. And both can only be stopped through the individual choices of people who have the opportunity to act. In “Scandal,” that’s Olivia Pope, and Huck, and David Rosen (if he gets his act together). With Scientology, “Going Clear” doesn’t offer any clear answers. There are the people who left—and they’re still being followed, harassed and denounced, even years and years later. Then there’s the rest of us, who have to do something with all of this information. I wonder if Rhimes heard about their hole and thought to create her own, and then write about dismantling that organization. And then brainstormed who to cast for an upcoming role, and made up her mind to reach out to Nazanin Boniadi, because someone should.

Shares