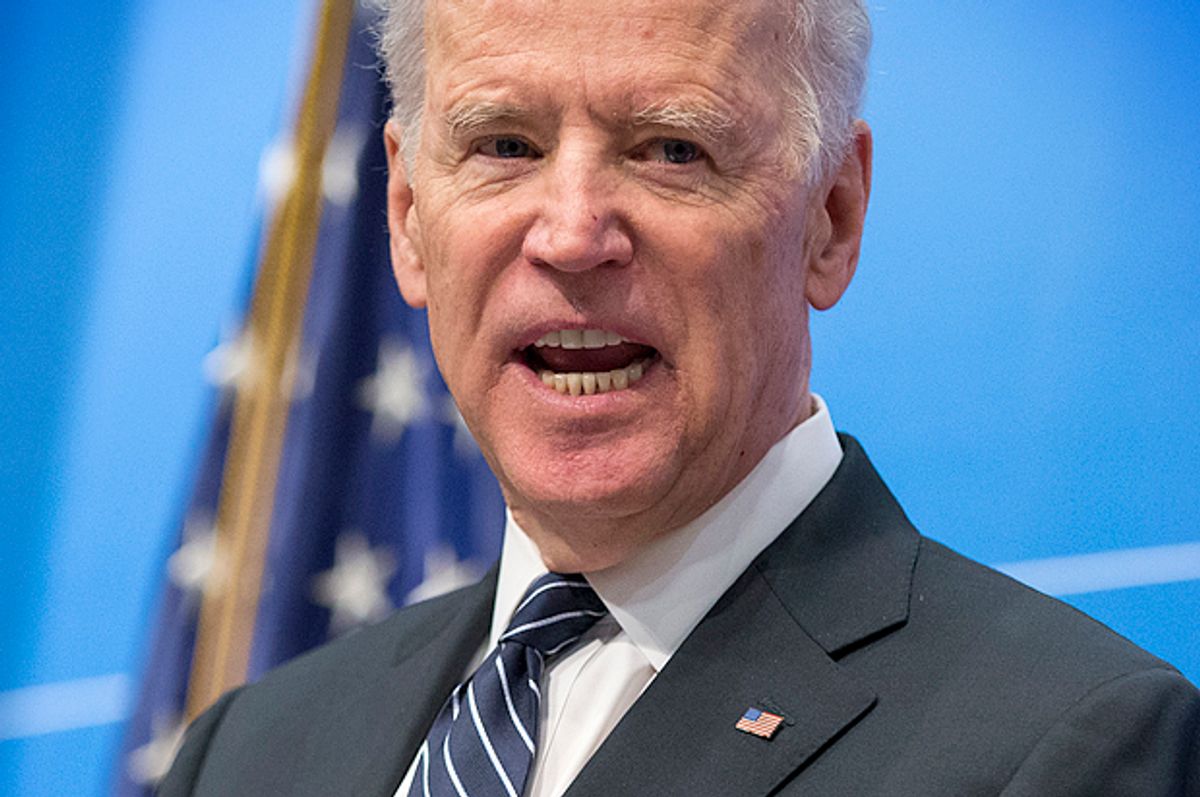

In the April issue of The Atlantic, Jeffrey Goldberg reports on a remarkable incident last fall at the residence of Vice President Joseph Biden. Speaking before guests—including leaders of Jewish organizations and Jewish officials in the Obama administration—invited to celebrate Rosh Hashanah, Biden recalled meeting Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir when he was a young man in the Senate:

“I’ll never forget talking to her in her office with her assistant—a guy named Rabin—about the Six-Day War,” he said. “The end of the meeting, we get up and walk out, the doors are open, and … the press is taking photos … She looked straight ahead and said, ‘Senator, don’t look so sad … Don’t worry. We Jews have a secret weapon.’”

He said he asked her what that secret weapon was.

“I thought she was going to tell me something about a nuclear program,” Biden continued. “She looked straight ahead and she said, ‘We have no place else to go.’” He paused, and repeated: “‘We have no place else to go.’”

“Folks,” he continued, “there is no place else to go, and you understand that in your bones. You understand in your bones that no matter how hospitable, no matter how consequential, no matter how engaged, no matter how deeply involved you are in the United States … there’s only one guarantee. There is really only one absolute guarantee, and that’s the state of Israel.”

When Biden was finished, Goldberg reports, “There was applause, and then photos, and then kosher canapés.”

Biden’s comments have attracted a fair amount of attention, not least from Goldberg, who was struck by their alarmist tone: “The vice president, it seemed to me, was trafficking in antiquated notions about Jewish anxiety.” Washington Post columnist Dana Milbank agrees with Goldberg “that Jews are safe and happy in the United States today.” But, he insists, “that could change.”

Yet no one has remarked upon the fact of a sitting vice president telling a portion of the American citizenry that they cannot count on the United States government as the ultimate guarantor of their freedom and safety. The Constitution, which the vice president is sworn to uphold, guarantees to American citizens the “Blessings of Liberty” and equal protection of the law. Despite that, despite “how deeply involved” Jews “are in the United States,” the occupant of the second-highest office in the land believes that American Jews should look to a foreign government as the foundation of their rights and security.

A country that once offered itself as a haven to persecuted Jews across the world now tells its Jews that in the event of some terrible outbreak of anti-Semitism they should… what? Plan on boarding the next plane to Tel Aviv? It’s like some crazy fiction from Philip Roth, except that when Roth contemplated an exodus in "Operation Shylock," it was to imagine the Jews fleeing Israel for Poland. Even in Roth’s "The Plot Against America," which does describe the triumph of European-style anti-Semitism in the U.S., it is not a foreign government but America itself that ultimately saves America’s Jews.

Imagine a vice president or president saying something similar to any other American ethnic group. To the Irish, say, long the victim of subjugation in their homeland and persecution and discrimination in the United States. Imagine a president telling the Irish that they shouldn’t consider the U.S. their real home, that they should keep their bags backed, a ticket to Dublin in the drawer, just in case.

In fact, when John F. Kennedy addressed the Irish Parliament in 1963, he said almost exactly the opposite of what Biden said. Like Biden, Kennedy affirmed his country’s commitment to the self-determination and sovereignty of a long oppressed people: “No people ever believed more deeply in the cause of Irish freedom than the people of the United States.” Like Biden, Kennedy was mindful that this long-oppressed people had not always been welcome in the U.S.:

They came to our shores in a mixture of hope and agony, and I would not underrate the difficulties of their course once they arrived in the United States…. It is no wonder that James Joyce described the Atlantic as a bowl of bitter tears.

Unlike Biden, however, Kennedy never envisioned Ireland as a refuge of last resort for the Irish of America; instead, Kennedy celebrated a continuing migration and return of the two peoples, a back and forth signifying the coming of age of freedom in the two nations. Ireland was no “longer a country of persecution, political or religious. It is a free country, and that is why any American feels at home” there. Likewise, the Irish in the U.S.

I am deeply honored to be your guest in a free Parliament in a free Ireland. If this nation had achieved its present political and economic stature a century or so ago, my great grandfather might never have left New Ross, and I might, if fortunate, be sitting down there with you. Of course if your own president had never left Brooklyn, he might be standing up here instead of me.

Both countries, in other words, offered liberty, security and opportunity to the Irish: that was their connection, their glue.

Perhaps the reason Biden’s recommendation has gone so unnoticed—despite Goldberg’s article being discussed in Commentary and Slate and on NPR—is that it speaks to a sentiment widely if privately shared in the Jewish community. As Milbank explains:

Eleven years ago, I carried my infant daughter into a synagogue basement and plunged her tiny body, head to toe, underwater.

She emerged sputtering and coughing, then wailing. The procedure, immersion in a Jewish ritual bath called a mikvah, felt barbaric. But it was for an important reason: Her mother isn’t Jewish, and by Jewish custom — and Israeli law — the faith is passed on by matrilineal descent, so I converted my daughter. Making sure she is Jewish in the eyes of the Jewish state gives me peace of mind. If the Gestapo ever comes again, she and her descendants will have a place to go. Just in case.

Even so, and even if Biden is just playing to his audience, it’s a stunning admission for a government official to make. Not just from the point of view of the Jewish citizens it hangs out to dry, but from the point of view of the government itself.

At the dawn of the modern era, the English political philosopher Thomas Hobbes wrote in "Leviathan" that “the obligation of subjects to the sovereign” should “last as long, and no longer, than the power lasteth by which he is able to protect them.” The ultimate reason for our submission to government is to ensure our protection; government secures our lives better than we, as individuals, can. “The end of obedience is protection.” If the government is not able to protect us—because it’s been toppled by a domestic insurrection or foreign power or because it’s simply too weak—or if the government actively seeks our destruction, we’re under no obligation to submit to it. We’re free to seek our protection elsewhere.

The late philosopher Bernard Williams called this Hobbesian principle “the ‘first’ political question.” It is “a necessary condition of legitimacy,” Williams explained, “that the state solve the first question,” that before justice or freedom or equality, the state secure “order, protection, safety, trust, and the conditions of cooperation.”

For reasons I’ve explored elsewhere, I don’t quite agree with Hobbes or Williams, but their formulation does reflect an influential, even dominant, strain in modern politics. It’s in the interest of each government to protect its citizens or at least to pretend that it is doing so. Once a government forsakes that principle, it loses its claim to legitimacy. It can’t expect its citizens to obey.

Just ask the FBI.

In the last year of his life, Malcolm X publicly broached an idea that had long been discussed in and occasionally aired by the Black Freedom movement. Instead of making demands on the U.S. government or passing civil rights legislation, why not, as he said in a May 30, 1964 interview, take “the case of the American Negro before the United Nations?” Having long abandoned African-Americans—indeed, having made war on African-Americans, whether in the form of slavery or the “slavery by another name” that was Jim Crow—the United States government should now expect to find itself abandoned by African-Americans. To protect their basic rights and security, African-Americans should look elsewhere, abroad, to seek some kind of intervention from an international body. At the UN, Malcolm announced a month later, “we can indict Uncle Sam for the continued criminal injustices that our people experience in this government.”

According to the late scholar Manning Marable, after Malcolm floated his proposal at a secret meeting of civil rights leaders convened at Sidney Poitier’s home in upstate New York, the FBI’s New York office immediately alerted the entire Bureau—as well as the Justice Department, the State Department, the CIA and other military agencies—that Malcolm wanted “to internationalize the civil rights movement by taking it to the United Nations.” Traveling in Africa that summer and fall, hoping to raise support for his plan from foreign leaders, Malcolm was subject to intense surveillance. If he “succeeded in convincing just one African Government to bring up the charge at the United Nations,” U.S. officials admitted, “the United States Government would be faced with a touchy problem.” The FBI and CIA followed his every move; Acting Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach asked J. Edgar Hoover to see whether Malcolm hadn’t violated the Logan Act while he was in Cairo. In Nairobi, Malcolm was personally dressed down by the U.S. Ambassador to Kenya.

Malcolm X was hardly the first American to denounce the racism and crimes of the U.S. government. And he was hardly the first American to make common cause with governments abroad or international bodies like the UN. What made his statements so incendiary and threatening to the U.S. government was his willingness to call into question, outside the confines of the nation, that nexus of obedience and protection that political philosophers have located at the foundation of the modern state.

Which brings us back to Joe Biden and his stunning remark last September. Often known to put his foot in his mouth, Biden may have simply been making some a version of a Kinsley gaffe, inadvertently revealing a widely shared conviction that most officials, if they thought about it for a second, would never dare to publicly admit.

The reason no one has been ruffled by his statement, I suspect, has less to do with any special sensitivity to Jewish experience than with an ancient, not altogether wholesome, notion that the Jews are somehow different. Historically, Jews were thought to be indigestible, never fully a part of the polity, exotic, other, with divided loyalties, not deserving or even worthy of the same respect or treatment accorded to other peoples.

Personally, I don’t have a problem with Jews wanting to be separate and apart, or even with their having divided loyalties (my problem with the State of Israel is of a different order). But it’s that issue of respect and equal treatment that bothers me, of the Jew being marked by the state for special handling, even when—especially when—it’s framed as an expression of compassion and sensitivity. I’m as leery of philosemitism as I am of anti-Semitism. While intended to demonstrate his intuitive knowledge of Jewish anxieties and empathy for Jewish concerns, Biden’s comment betrays, in its Bideneseque way, an almost blasé conviction that, in the end, the Jew doesn’t really belong here, that his real home lies elsewhere.

When it comes to Israel, it’s often said, the normal rules don’t apply. When compared to the experience of Malcolm X or the statements of JFK, Biden’s remarks suggest that that’s true. But it’s not just Israel that’s being treated as an exception here. It’s the Jews. And that’s not something that should be applauded. Least of all by Jews.

Shares