On ______, a group of ______ heavily armed, black-clad men burst into a ______ in ______, opening fire and killing a total of ______ people.

The attackers were filmed shouting “Allahu akbar!”Speaking at a press conference, President ______ said: “We condemn this criminal act by extremists. Their attempt to justify their violent acts in the name of a religion of peace will not, however, succeed. We also condemn with equal force those who would use this atrocity as a pretext for Islamophobic hate crimes.”

As I revised the introduction to this book, four months before its publication, I could of course have written something more specific, like this:

On January 7, 2015, two heavily armed, black-clad attackers burst into the offices of Charlie Hebdo in Paris, opening fire and killing a total of ten people. The attackers were filmed shouting “Allahu akbar!”

But, on reflection, there seemed little reason to pick Paris. Just a few weeks earlier I could equally as well have written this:

In December 2014, a group of nine heavily armed, black-clad men burst into a school in Peshawar, opening fire and killing a total of 145 people.

Indeed, I could have written a similar sentence about any number of events, from Ottawa, Canada, to Sydney, Australia, to Baga, Nigeria. So instead I decided to leave the place blank and the number of killers and victims blank, too. You, the reader, can simply fill them in with the latest case that happens to be in the news. Or, if you prefer a more historical example, you can try this:

In September 2001, a group of 19 Islamic terrorists flew hijacked planes into buildings in New York and Washington, D.C., killing 2,996 people.

For more than thirteen years now, I have been making a simple argument in response to such acts of terrorism. My argument is that it is foolish to insist, as our leaders habitually do, that the violent acts of radical Islamists can be divorced from the religious ideals that inspire them. Instead we must acknowledge that they are driven by a political ideology, an ideology embedded in Islam itself, in the holy book of the Qur’an as well as the life and teachings of the Prophet Muhammad contained in the hadith.

Let me make my point in the simplest possible terms: Islam is not a religion of peace.

For expressing the idea that Islamic violence is rooted not in social, economic, or political conditions—or even in theological error—but rather in the foundational texts of Islam itself, I have been denounced as a bigot and an “Islamophobe.” I have been silenced, shunned, and shamed. In effect, I have been deemed to be a heretic, not just by Muslims—for whom I am already an apostate—but by some Western liberals as well, whose multicultural sensibilities are offended by such “insensitive” pronouncements.

My uncompromising statements on this topic have incited such vehement denunciations that one would think I had committed an act of violence myself. For today, it seems, speaking the truth about Islam is a crime. “Hate speech” is the modern term for heresy. And in the present atmosphere, anything that makes Muslims feel uncomfortable is branded as “hate.”

In these pages, it is my intention to make many people—not only Muslims but also Western apologists for Islam—uncomfortable. I am not going to do this by drawing cartoons. Rather, I intend to challenge centuries of religious orthodoxy with ideas and arguments that I am certain will be denounced as heretical. My argument is for nothing less than a Muslim Reformation. Without fundamental alterations to some of Islam’s core concepts, I believe, we shall not solve the burning and increasingly global problem of political violence carried out in the name of religion. I intend to speak freely, in the hope that others will debate equally freely with me on what needs to change in Islamic doctrine, rather than seeking to stifle discussion.

Let me illustrate with an anecdote why I believe this book is necessary.

In September 2013, I was flattered to be called by the then president of Brandeis University, Frederick Lawrence, and offered an honorary degree in social justice, to be conferred at the university’s commencement ceremony in May 2014. All seemed well until six months later, when I received another phone call from President Lawrence, this time to inform me that Brandeis was revoking my invitation. I was stunned. I soon learned that an online petition, organized initially by the Council on American Islamic Relations (CAIR) and located at the website change.org, had been circulated by some students and faculty who were offended by my selection.

Accusing me of “hate speech,” the change.org petition began by saying that it had “come as a shock to our community due to her extreme Islamophobic beliefs, that Ayaan Hirsi Ali would be receiving an Honorary Degree in Social Justice this year. The selection of Hirsi Ali to receive an honorary degree is a blatant and callous disregard by the administration of not only the Muslim students, but of any student who has experienced pure hate speech. It is a direct violation of Brandeis University’s own moral code as well as the rights of Brandeis students.” In closing, the petitioners asked: “How can an Administration of a University that prides itself on social justice and acceptance of all make a decision that targets and disrespects it’s [sic] own students?” My nomination to receive an honorary degree was “hurtful to the Muslim students and the Brandeis community who stand for social justice.”

No fewer than eighty-seven members of the Brandeis faculty had also written to express their “shock and dismay” at a few brief snippets of my public statements, mostly drawn from interviews I had given seven years before. I was, they said, a “divisive individual.” In particular, I was guilty of suggesting that:

violence toward girls and women is particular to Islam or the Two-Thirds World, thereby obscuring such violence in our midst among non-Muslims, including on our own campus [and] . . . the hard work on the ground by committed Muslim feminist and other progressive Muslim activists and scholars, who find support for gender and other equality within the Muslim tradition and are effective at achieving it.

On scrolling down the list of faculty signatories, I was struck by the strange bedfellows I had inadvertently brought together. Professors of “Women’s, Gender and Sexuality Studies” lining up with CAIR, an organization subsequently blacklisted as a terrorist organization by the United Arab Emirates? An authority on “Queer/Feminist Narrative Theory” siding with the openly homophobic Islamists?

It is quite true that in February 2007, when I still resided in Holland, I told the London Evening Standard: “Violence is inherent in Islam.” This was one of three brief, selectively edited quotations to which the Brandeis faculty took exception. What they omitted to mention in their letter was that, less than three years before, my collaborator on a short documentary film, Theo van Gogh, had been murdered in the street in Amsterdam by a young man of Moroccan parentage named Mohammed Bouyeri. First he shot Theo eight times with a handgun. Then he shot him again as Theo, still clinging to life, pleaded for mercy. Then he cut his throat and attempted to decapitate him with a large knife. Finally, using a smaller knife, he stuck a long note to Theo’s body.

I wonder how many of my campus critics have read this letter, which was structured in the style of a fatwa, or religious verdict. It began, “In the name of Allah—the Beneficent—the Merciful” and included, along with numerous quotations from the Qur’an, an explicit threat on my life:

My Rabb [master] give us death to give us happiness with martyrdom. Allahumma Amen [Oh, Allah, please accept]. Mrs. Hirshi [sic] Ali and the rest of you extremist unbelievers. Islam has withstood many enemies and persecutions throughout History. . . . AYAAN HIRSI ALI YOU WILL SELF-DESTRUCT ON ISLAM!

On and on it went in the same ranting vein. “Islam will be victorious through the blood of the martyrs. They will spread its light in every dark corner of this earth and it will drive evil with the sword if necessary back into its dark hole. . . . There will be no mercy shown to the purveyors of injustice, only the sword will be lifted against them. No discussions, no demonstrations, no petitions.” The note also included this passage, copied directly from the Qur’an: “Be warned that the death that you are trying to prevent will surely find you, afterwards you will be taken back to the All Knowing and He will tell you what you attempted to do” (62:8).

Perhaps those who have risen to the rarefied heights of the Brandeis faculty can devise a way of arguing that no connection exists between Bouyeri’s actions and Islam. I can certainly remember Dutch academics claiming that, behind his religious language, Bouyeri’s real motivation in wanting to kill me was socioeconomic deprivation or postmodern alienation. To me, however, when a murderer quotes the Qur’an in justification of his crime, we should at least discuss the possibility that he means what he says.

Now, when I assert that Islam is not a religion of peace I do not mean that Islamic belief makes Muslims naturally violent. This is manifestly not the case: there are many millions of peaceful Muslims in the world. What I do say is that the call to violence and the justification for it are explicitly stated in the sacred texts of Islam. Moreover, this theologically sanctioned violence is there to be activated by any number of offenses, including but not limited to apostasy, adultery, blasphemy, and even something as vague as threats to family honor or to the honor of Islam itself.

Yet from the moment I first began to argue that there was an unavoidable connection between the religion I was raised in and the violence of organizations such as Al-Qaeda and the self-styled Islamic State (henceforth IS, though others prefer the acronyms ISIS or ISIL), I have been subjected to a sustained effort to silence my voice.

Death threats are obviously the most troubling form of intimidation. But there have also been other, less violent methods. Muslim organizations such as CAIR have tried to prevent me from speaking freely, particularly on university campuses. Some have argued that because I am not a scholar of Islamic religion, or even a practicing Muslim, I am not a competent authority on the subject. In other venues, select Muslims and Western liberals have accused me of “Islamophobia,” a word designed to be equated with anti-Semitism, homophobia, or other prejudices that Western societies have learned to abhor and condemn.

Why are these people impelled to try to silence me, to protest against my public appearances, to stigmatize my views and drive me off the stage with threats of violence and death? It is not because I am ignorant or ill-informed. On the contrary, my views on Islam are based on my knowledge and experience of being a Muslim, of living in Muslim societies—including Mecca itself, the very center of Islamic belief—and on my years of study of Islam as a practitioner, student, and teacher. The real explanation is clear. It is because they cannot actually refute what I am saying. And I am not alone. Shortly after the attack on Charlie Hebdo, Asra Nomani, a Muslim reformer, spoke out against what she calls the “honor brigade”—an organized international cabal hell-bent on silencing debate on Islam.

The shameful thing is that this campaign is effective in the West. Western liberals now seem to collude against critical thought and debate. I never cease to be amazed by the fact that non-Muslims who consider themselves liberals—including feminists and advocates of gay rights—are so readily persuaded by these crass means to take the Islamists’ side against Muslim and non-Muslim critics.

*

In the weeks and months that followed, Islam was repeatedly in the news—and not as a religion of peace. On April 14, six days after Brandeis’s disinvitation, the violent Islamist group Boko Haram kidnapped 276 schoolgirls in Nigeria. On May 15, in Sudan, a pregnant woman, Meriam Ibrahim, was sentenced to death for the crime of apostasy. On June 29, IS proclaimed its new caliphate in Iraq and Syria. On August 19, the American journalist James Foley was beheaded on video. On September 2, Steven Sotloff, also an American journalist, shared this fate. The man presiding over their executions was clearly identifiable as being British educated, one of between 3,000 and 4,500 European Union citizens who have become jihadists in Iraq and Syria. On September 26, a recent convert to Islam, Alton Nolen, beheaded his co-worker Colleen Hufford at a food-processing plant in Moore, Oklahoma. On October 22, another criminal turned Muslim convert, named Michael Zehaf-Bibeau, ran amok in the Canadian capital, Ottawa, fatally shooting Corporal Nathan Cirillo, who was on sentry duty. And so it has gone on ever since. On December 15, a cleric named Man Haron Monis took eighteen people hostage in a Sydney café; two died in the resulting shoot-out. Finally, just as I was finishing this book, the staff of the satirical French weekly Charlie Hebdo were massacred in Paris. Masked and armed with AK-47 rifles, the Kouachi brothers forced their way into the offices of the magazine and killed the editor, Stéphane Charbonnier, along with nine other employees and a police officer. They killed another police officer in the street. Within hours, their associate Amedy Coulibaly killed four people, all of them Jewish, after seizing control of a kosher store in the east of the city.

In every case, the perpetrators used Islamic language or symbols as they carried out their crimes. To give a single example, during their attack on Charlie Hebdo, the Kouachis shouted “Allahu akbar” (“God is great”) and “the Prophet is avenged.” They told a female member of the staff in the offices they would spare her “because you are a woman. We do not kill women. But think about what you are doing. What you are doing is bad. I spare you, and because I spare you, you will read the Qur’an.”

If I had needed fresh evidence that violence in the name of Islam was spreading not only across the Middle East and North Africa but also through Western Europe, across the Atlantic and beyond, here it was in lamentable abundance.

After Steven Sotloff’s decapitation, Vice President Joe Biden pledged to pursue his killers to the “gates of hell.” So outraged was President Barack Obama that he chose to reverse his policy of ending American military intervention in Iraq, ordering air strikes and deploying military personnel as part of an effort to “degrade and ultimately destroy the terrorist group known as ISIL.” But the president’s statement of September 10, 2014, is worth reading closely for its critical evasions and distortions:

Now let’s make two things clear: ISIL is not “Islamic.” No religion condones the killing of innocents. And the vast majority of ISIL’s victims have been Muslim. And ISIL is certainly not a state. . . . ISIL is a terrorist organization, pure and simple. And it has no vision other than the slaughter of all who stand in its way.

In short, Islamic State was neither a state nor Islamic. It was “evil.” Its members were “unique in their brutality.” The campaign against it was like an effort to eradicate “cancer.”

After the Charlie Hebdo massacre, the White House press secretary went to great lengths to distinguish between “the violent extremist messaging that ISIL and other extremist organizations are using to try to radicalize individuals around the globe” and a “peaceful religion.” The administration, he said, had “enjoyed significant success in enlisting leaders in the Muslim community . . . to be clear about what the tenets of Islam actually are.” The very phrase “radical Islam” was no longer to be uttered.

But what if this entire premise is wrong? For it is not just Al-Qaeda and IS that show the violent face of Islamic faith and practice. It is Pakistan, where any statement critical of the Prophet or Islam is labeled as blasphemy and punishable by death. It is Saudi Arabia, where churches and synagogues are outlawed, and where beheadings are a legitimate form of punishment, so much so that there was almost a beheading a day in August 2014. It is Iran, where stoning is an acceptable punishment and homosexuals are hanged for their “crime.” It is Brunei, where the sultan is reinstituting Islamic sharia law, again making homosexuality punishable by death.

We have now had almost a decade and a half of policies and pronouncements based on the assumption that terrorism or extremism can and must be differentiated from Islam. Again and again in the wake of terrorist attacks around the globe, Western leaders have hastened to declare that the problem has nothing to do with Islam itself. For Islam is a religion of peace.

These efforts are well meaning, but they arise from a misguided conviction, held by many Western liberals, that retaliation against Muslims is more to be feared than Islamist violence itself. Thus, those responsible for the 9/11 attacks were represented not as Muslims but as terrorists; we focused on their tactics rather than on the ideology that justified their horrific acts. In the process, we embraced those “moderate” Muslims who blandly told us Islam was a religion of peace and marginalized dissident Muslims who were attempting to pursue real reform.

Today, we are still trying to argue that the violence is the work of a lunatic fringe of extremists. We employ medical metaphors, trying to define the phenomenon as some kind of foreign body alien to the religious milieu in which it flourishes. And we make believe that there are extremists just as bad as the jihadists in our own midst. The president of the United States even went so far as to declare, in a speech to the United Nations General Assembly in 2012: “The future must not belong to those who slander the Prophet of Islam”—as opposed, presumably, to those who go around killing the slanderers.

Some people will doubtless complain that this book slanders Muhammad. But its aim is not to give gratuitous offense, but to show that this kind of approach wholly—not just partly, but wholly—misunderstands the problem of Islam in the twenty-first century. Indeed, this approach also misunderstands the nature and meaning of liberalism.

For the fundamental problem is that the majority of otherwise peaceful and law-abiding Muslims are unwilling to acknowledge, much less to repudiate, the theological warrant for intolerance and violence embedded in their own religious texts.

It simply will not do for Muslims to claim that their religion has been “hijacked” by extremists. The killers of IS and Boko Haram cite the same religious texts that every other Muslim in the world considers sacrosanct. And instead of letting them off the hook with bland clichés about Islam as a religion of peace, we in the West need to challenge and debate the very substance of Islamic thought and practice. We need to hold Islam accountable for the acts of its most violent adherents

and demand that it reform or disavow the key beliefs that are used to justify those acts.

At the same time, we need to stand up for our own principles as liberals. Specifically, we need to say to offended Western Muslims (and their liberal supporters) that it is not we who must accommodate their beliefs and sensitivities. Rather, it is they who must learn to live with our commitment to free speech.

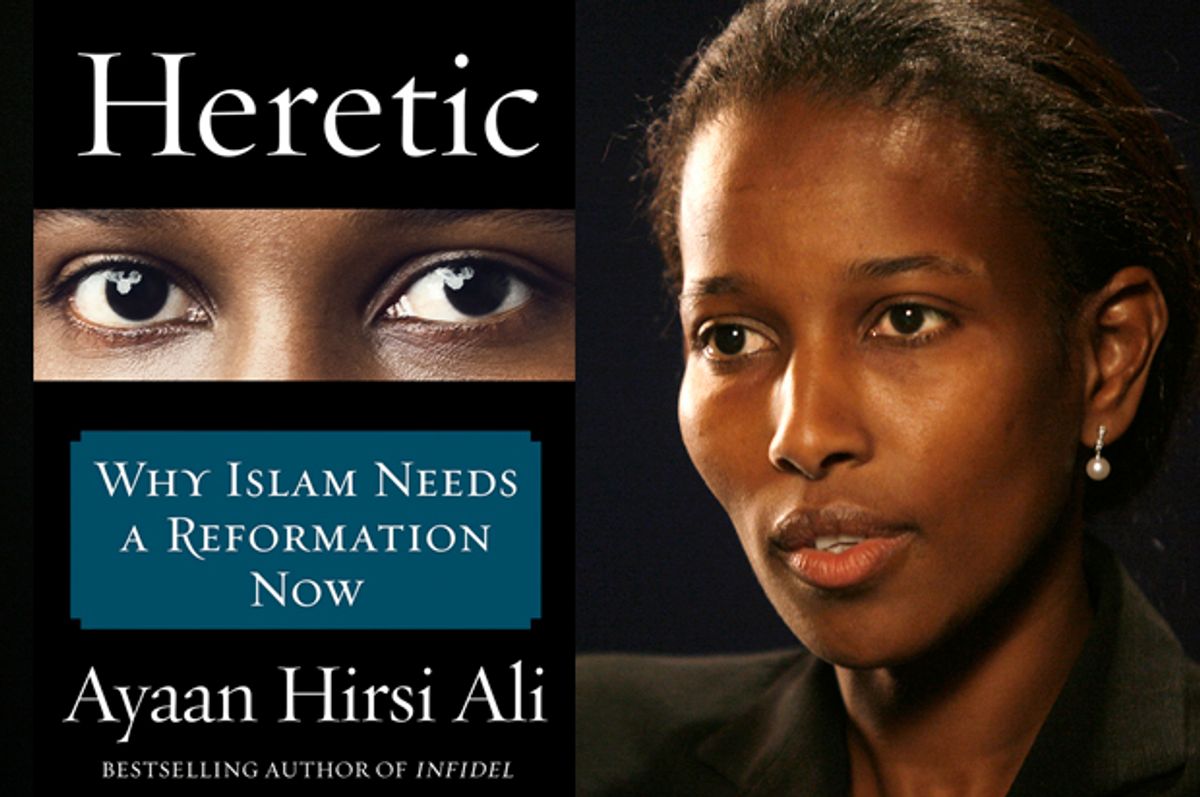

Excerpted from "Heretic: Why Islam Needs a Reformation Now" by Ayaan Hirsi Ali. Published by Harper, an imprint of Harper Collins Publishers. Copyright © 2015 by Ayaan Hirsi Ali. Reprinted with permission of the publisher. All rights reserved.

Shares