In a day in late August 1966, my little village woke to the fading edge of summer and the beginning of a new school year. A quiet dawn betrayed scarcely any sign of agitation within the placid houses, grouped under pecan or oak or elm trees, taking comfort in the shade even at that early hour, already touched with the beginnings of heat. On the main highway through town a single stoplight shuttered through its changes from red to yellow to green. The lone restaurant opened a bit past dawn to serve country breakfast to truckers and travelers and locals. Post-office workers arrived to sort mail, one or two storekeepers opened their doors, and the owner of the Trent Motel shuffled check-in forms at the front desk while the neon vacancy sign glowed in the window.

Beyond main street under the ranks of trees wakened the rest of the village, black residents in the rows of houses we called Back Streets, white residents in the houses we thought of as Pollocksville proper, the real place, the real world. Outside the town limits, scattered among the fields and forests of Jones County, farmers were already abroad in the early morning, continuing the tobacco harvest, readying the cured, golden leaves for market. A couple of miles from town, a clerk opened the local Alcoholic Beverage Control store, collapsing the iron security barrier against the walls, stepping behind his long counter, shelves of liquor bunched behind him in the small space. In North Carolina, liquor could be sold legally only in ABC stores, and ours was located outside of the village, decently separate from our homes and churches.

Down the highway, closer to the old Methodist church, Mrs. Willa Romley opened her fish market. At another busy intersection, Mr. Paul Arnett unlocked his thriving store on the route to the beaches. Across the county, school bus drivers, all of them students at the high school, swept their buses and started their engines. The first of the teachers arrived to inspect the classrooms.

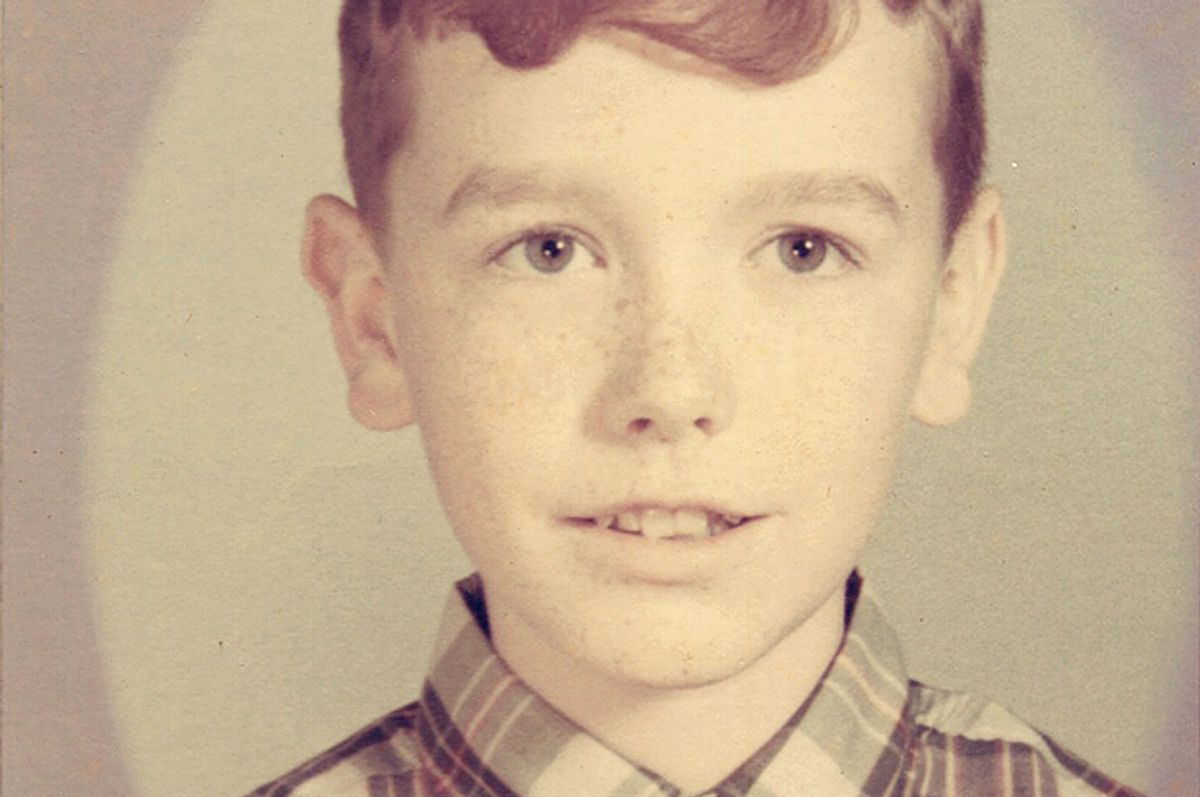

I had begun my morning, too, slipping out of bed, skinny and pale, my white jockey shorts, my hairless body, all of me destined to begin sixth grade that morning. What I felt was mostly sadness that the free days of summer break were over. I dressed in stiff new clothes in the bedroom I shared with my brothers, new jeans and a short-sleeved shirt, a plaid that I liked, the starchy smell like a perfume in my nostrils. The night before I had carefully removed the tags, pins, and excess labels from my jeans and shirt, from my new socks and belt. New shoes made a bit of a squeaking sound as I stepped to the window to look out at the side yard. At eleven, I was in a brooding state, in my third year as a baptized Christian and member of the Pollocksville Baptist Church, attempting to resolve a belief in God with the world as I understood it from the novels of Robert A. Heinlein, P. L. Travers, Madeleine L’Engle, and Edgar Rice Burroughs. My life for the summer had revolved around Vacation Bible School, reruns of Batman, and walks to the public library to borrow more books. I had saved my allowance for trips to the local drugstore, where I purchased DC and Marvel comic books and read them while sipping a vanilla Coke. I wandered and daydreamed in a patch of woods on the other side of the old Jenkins Gas Company building, and read the Bible and prayed. A couple of times a week I talked to my best friend, Marianne.

On my mind that morning was the coming of the fall broadcast television season, now only a few days away, when shows like The Monkees and Star Trek were advertised to premiere. That was my consolation for the end of summer. I would be entering a new grade at school, and would have my first male teacher. I would also be going to school with black children for the first time.

On the phone with Marianne, I must have mentioned this last subject to her at some point, or she must have mentioned it to me, and we shared some opinion about it. We had been talking regularly that summer, which made her practically my girlfriend, a thought that gave me a certain pleasure and a certain discomfort. Most of the time we discussed Prince Charles of England, Herman’s Hermits, Paul Revere & the Raiders, other pop bands whose music we heard that summer on American Bandstand. She had told me about her family, her brother who was really her half brother, her mother who had divorced her first husband, her family that counted the King of England in its ancestry. I told her about books I was reading and the work I was doing in the family’s vegetable garden. My family had no famous ancestors, as far as I knew.

Somewhere in all of that, we must have mentioned the fact that we would be going to school with black children in the fall.

I can no longer recall what it was like to be endlessly fascinated with Marianne’s accounts of what she had read in Tiger Beat, or with speculation about the coming television season, or the next rocket launch, or whether people could read each other’s minds if they tried really hard. What I can remember is that these were the important issues in general, whereas the news that our school classroom would include three colored girls was harder to digest. We knew what it meant to like a song or think a singer was pretty or cute. We had no idea what it meant that this change called integration was coming. If we spoke of it at all, it would have been to speculate about how many black kids we would get in our sixth-grade class, or to reassure ourselves that there would still be mostly white people in our school.

Marianne and I had been in the same class with the same children for all five years of our education, Pollocksville being so small that there were only enough white children to fill one classroom for each grade, one through eight. At the time, I thought all schools operated in this tidy way and was appalled to learn that in New Bern, close to us, there were two or three sections of first graders and they went to school in different classrooms. All my life I had lived in a community where whites and blacks were legally separated from one another. To the degree that I knew anything about this situation, I thought it was the natural shape of the world. Now, suddenly, there was a law that said any child could choose to attend either the white or the black school system.

The thought that I would have to sit next to black children had made me fearful when I first heard it. The fear came from what I had already learned about race, though if asked, I would likely have denied that I had been taught anything at all. To the degree that I understood the fear, I knew it came from a feeling that the world was rearranging itself, the shift being bigger than I could take in. I had a quiet conviction that change was unfair in some way, because I had hardly gotten to know the old world, when, suddenly, here was the new.

I felt the same fear when I saw news stories about demonstrations against the war in Vietnam, race riots in the inner cities, and the possibility of nuclear war. The world was burning before I had even had a chance to grow up and enjoy it. A hollow settled into my middle at such times, and I found another Heinlein novel, maybe The Star Beast or Have Space Suit —Will Travel, and escaped into the future.

Exactly what had happened to bring about the new world I was not sure. Outside of school or church, adults rarely explained history or taught about how things worked, leaving us children to figure things out as best we could. Nobody ever told me why blacks and whites had to go to separate schools, use separate restrooms, and keep a distance from one another. No one ever pointed out a black person to me and said, “You cannot drink water out of the same glass as that person, or call him ‘sir,’ or sit next to him in a public place.” Yet the knowledge of those truths had come into me in spite of the silence.

At church, Mr. Russell sometimes declared that God did not intend for the races to mix. He owned the only restaurant in Pollocksville, so the issue concerned him, since he had recently been forced by law to serve colored customers. According to his worldview, black people had their place just like white people had theirs. They did not want to associate with us any more than we wanted to associate with them. This was a statement I would hear echoed in other voices at other times. At church, Mr. Russell would not have used the word "n***er," but in his restaurant he would have. His was a voice I remember, and some people in the small congregation agreed with what he said. Others did not. So the uncomfortable subject never took the center of our discussions, which were largely concerned with choir practice, the building fund for the new church, and the fact that too many of the girls were wearing those new miniskirts to Sunday service.

Likely at church I had heard the term “Freedom of Choice,” the name of the new law that maintained separate school systems for blacks and whites while allowing for a certain degree of race-mixing. After service, having been reminded of their salvation during the preacher’s sermon, adults stood in front of the sanctuary and talked a bit, especially in the warm months, which in eastern North Carolina comprised most of the year. I wandered among them sometimes and listened to their deep voices, their serious tones, watching as the men adjusted their ties and the women fondled their purses. Church was one of the rare places where I heard adults talk, and where they discussed the government, the war in Vietnam, and politics.

As I dressed for school that morning, I combed my hair carefully in the way that my mother had taught me, parted on the side, with a little flip at the front that she called a rabbit hill. My mother inspected it and approved. There were four children to get ready for school, and Mother herself also worked there, in the cafeteria, so she would be driving the few blocks. But I had decided to walk to school. We had lived in the village proper only a few months, and I was still delighted with the novelty. The town was huge to my eyes, and I felt immeasurably more important now that we lived in it. On leaving the house with my new notebook and pencil case, I listened to the starched sound of my new jeans with each step. I had rolled up the cuffs of the jeans over my new black shoes. The clothes felt like a kind of carapace, my shirt collar so stiff it poked at my neck. As soon as I was out of sight of the house, I rubbed the rabbit hill out of my hair. It had become important to me, lately, to take some control of the way I looked.

My thoughts were on the trivialities of the day, or my family’s troubles, or the fact that I would see Marianne again. I was thinking about the fact that I would have Mr. Roger Vaughn as my teacher this year, when my first five teachers had all been women. In the same fashion, my conversations with my mother that morning were about what cereal I would eat for breakfast; that I should eat even if I wasn’t hungry, because I would be hungry later; and that she thought I could wear my shirts to school twice before they needed to be washed. As in so many other cases, the biggest issue, the biggest change, went unspoken and unmarked. Never once did any adult give me any advice about how to treat the new black students in our school. On the rare occasions when I heard adults discuss integration, they spoke to one another in the coded, guarded manner typical of adults, presuming a knowledge I had yet to gain.

So I walked into the classroom and took a seat in a desk at the head of a row. The room was quiet, as best I can recall, more so than normal for a first day of school, with Mr. Vaughn sitting at his desk, droopy-eyed, nose covered with veins twining this way and that, tanned like leather from a summer at Bogue Sound. None of the school buses had arrived yet.

The three black girls walked into the classroom together, each holding a notebook and a purse. They had a wary air to them, faces stiff and frozen. As I recall, they were escorted into the room by the principal, Miss Julia Whitty, who introduced them to Mr. Vaughn and, in saying their names, spread the introduction to the rest of us as well. Violet, Ursula, and Rhonda. Miss Whitty was smiling, speaking in her confident voice, fingering the glasses she wore on a chain around her neck. She treated the girls as if they were simply new students who had moved to Pollocksville, though she knew as well as anyone that new students hardly ever moved to Pollocksville, and certainly not three at a time. In the way of beginnings, this was all. The girls took their seats.

One of them, Violet, sat in the desk behind mine. Ursula sat behind her, and Rhonda sat across the aisle. Violet’s last name was Strahan. Both Rhonda and Ursula were named Doleman. They were sisters. I remember being mildly surprised at two sisters in the same grade of school. By that age I knew where babies came from and how long it took for them to arrive.

The girls talked to those of us sitting nearby that first day, but I have no recollection of what we said to one another. The three girls were very different from each other, and I stared at them a good bit. Violet was large, almost barrel-shaped, with very small breasts tucked up high on her ribs. She wore her hair short. I don’t recall whether she straightened her hair that first day or whether she wore it natural, in the style that was called an Afro. Her skin was polished and smooth. Given the heat, she often wore sleeveless dresses, and in my recollection that is what she wore the first day of school, her arms perfectly smooth, a bit thin compared to the density of her torso. She spoke in a powerful voice, so much so that it was hard for her to whisper. She had fierce, hard eyes. Whenever she moved in her desk, it rocked against mine.

Ursula was younger in affect, with a pretty, rounded face and a softly curved body. She looked ample and plump, her movements betraying a certain shyness, her eyes gentle. She had the look of someone who could be friendly, who could be trusted. When she spoke, her voice was easy and lilting. She tugged at her dress from time to time, as if she were self-conscious about it, or as if it were too tight.

Rhonda had big brown eyes, long, straight hair, and a face that was lovely to watch. She carried herself with a liveliness, a sense of herself, that was complete, and she had an air of confidence that verged on defiance. She wore a pleated skirt and blouse that first day, or, at least, that is the way I will draw her. What she wore drew stylishness from her way of carrying herself, the fact that she knew who she was. Her pride was unshakable.

They sat among us thirty-odd white children, composed and prepared for whatever might come. The rest of us, who knew each other so well from five long years in classroom and on playground, who had grown so used to each other, who had established our social order, suddenly found our world was much different than before. We had dealt with few newcomers to our group.

A bell rang. Mr. Vaughn gave the clock over the door a bleary, yellow-eyed look. School began.

Marianne had come to school in her mother’s car, as she always did, wearing her brown hair tied behind her head with a girlish ribbon, her blouse with a sort of sailor’s bib, her pale legs under a modest skirt. She had a mouth full of braces that made her talk a bit moist at times. I can’t recollect where she sat that first day of school, though she, Virginia, and I would contrive to sit close to one another for most of that year.

I don’t recall much in the way of conversation, though we must have chattered as we always did, not simply Marianne and me but all the rest of us. The boys snickered in the back of the room, told dirty jokes, had farting contests, and talked about their weekend at Catfish Lake. Friends in adjacent desks whispered to one another, girls sharing chewing gum, which they were not supposed to chew, sliding the gum into their mouths in secret.

Marianne and I talked about Batman, maybe, or about the new show Star Trek that would premiere in a few days. She might have brought an issue of Tiger Beat to school that day, in which case she showed me a picture of her secret crush, the guitarist for Herman’s Hermits, Derek Leckenby, who rivaled Prince Charles for her affections. I can hardly remember what I contributed to these conversations.

At my back was Violet Strahan, the black girl, sitting in the desk behind me.

I had an impulse to say something to her, to call her a name. Of my memories of that day, this moment comes to me the most clearly. I had a feeling it would be funny to call Violet a name, and I knew I was daring enough to do it. The feeling of that thought in my head is far more vivid than any other detail of the beginning of school. I am fairly certain that this happened either on the first day of school or soon after. I knew that calling Violet a name would make the boys at the back of the room laugh. That moment inside my head rings down through the years so clearly. I was eleven years old, filled with a vague sense of purpose, and ready to do my part, though for what, I could not have said.

The moment was clear, sunny. Mr. Vaughn had left us unattended for some reason, maybe to smoke a cigarette in the teachers’ lounge. Our schoolroom had fifteen-foot ceilings that made the sound of our chatter ring, and windows that nearly reached to the top of the ceiling. The windows would have been open, maybe a breeze coming through to stir the heat. I had the impulse to speak again, and I turned to Violet, and a moment of silence fell over the classroom, into which I said the words I had been planning. “You black bitch,” I said, and some of the white boys looked at me and grinned. People giggled nervously.

Violet hardly even blinked. “You white cracker bitch,” she said back to me, without hesitation, and cocked an eyebrow and clamped her jaw together.

I sat dumbfounded. There had been no likelihood, in my fantasy, that she could speak back. A flush came to my face.

“You didn’t think I’d say that, did you?” Her voice was even louder than before, and her eyes flashed with a kind of angry light. Everybody was listening. The laughter had stopped. “Black is beautiful. I love my black skin. What do you think about that?”

“You are a black bitch,” I said again, stupidly, blushing. Some of the white students continued to snicker and I could tell they thought I was really brave. But the moment did not make me feel the way I had thought it would.

“And you a white one,” she said, folding her arms across her chest.

Pretty soon after that Mr. Vaughn returned. The moment came to an abrupt end. Violet said nothing further about what I called her. All the rest of the day, I could feel her gaze boring into my back.

She had reacted to my declaration in an unexpected way. When I called her that name, she was supposed to be ashamed, she was supposed to duck her head or cringe or admit that I was right, that she had no business being in our white classroom. If I had followed my thought far enough, this is what I would have found. But she took my insult as a matter of course and returned it. In her sharp eyes and fearlessness were evidence of a spirit tough as flint, a person unlike any of the milder beings around me.

She had a voice so big it pushed me back into my desk. To make such a sound come out of herself caused her no self-consciousness. I could sing loud in the choir but otherwise I spoke quietly. She was very different from me, but not in the ways I expected.

She was real. Her voice was big and it reached inside me. That moment lingered in my head for the rest of the day. It had ended abruptly. She had not told the teacher what I had said. We were two children, having an odd kind of fight. She had not tattled. Why had I called her that name? I used cuss words so rarely the other kids usually giggled when I did.

If I was superior to her, as I had always been told I was, why didn’t she feel it, too?

Excerpted from “How I Shed My Skin: Unlearning the Racist Lessons of a Southern Childhood” by Jim Grimsley. Copyright © 2015 by Jim Grimsley. Reprinted by arrangement with Algonquin Books. All rights reserved.

Shares