The first time I traveled to Georgia’s Montgomery County, in 2002, it felt like a very familiar and friendly American suburb. Kids were cheering at the local high school’s homecoming parade. The community appeared to be very mixed and well integrated. So it was a big shock to see, on the school ballot for homecoming queens, two columns: one for a white queen and another for a black queen. Though it was integrated in 1971, Montgomery County High School held on to a tradition of segregating proms and homecoming activities by race.

The disconnect between the friendliness I saw among Montgomery County’s neighbors and the overt segregation I discovered in its community fascinated and haunted me. It hinted at dark communal secrets and painful, untold individual stories. When I began photographing Montgomery County High School students in 2002, the cultural conversation about racism in America felt like a distant history lecture. This was, in the here and now, injustice and painful humiliation endured by kids I knew.

When I began this project, racism in America seemed like a taboo subject. That’s why I was determined to get underneath the surface as I returned to South Georgia again and again. And that’s why institutional racism—not just in the Deep South but across the country as well—is so pernicious. In our courts, plaintiffs are not even allowed to bring up race unless the defendant utters an explicit racial slur while committing the crime. The simple fact that our legal institutions don’t acknowledge that race plays a major role in our sense of justice shows the depth of the problem. There aren’t “Colored Only” entrances anymore, but it’s almost as bad when there is official silence on racism and segregation.

After Montgomery County High School proms were finally integrated in 2010, I returned to Georgia to document a hopeful story. I believe it’s important to convey how far we’ve come in the last several decades, just as it’s important to explain how much work we still have left to do when it comes to racial justice. I intended to show how a small town was going through slow and sometimes painful changes, and I followed Keyke Burns, an astounding young woman who weaves together the three narratives of my film Southern Rites.

Around the time that the prom became integrated, Keyke’s father, Calvin, found major support across color lines in his bid to become Montgomery County’s first African American sheriff, an especially historic feat given that he had received death threats when he announced his intention to run years prior. His campaign added another optimistic thread to my film. But then tragedy struck, and a third, far more troubling story emerged as the central narrative of Southern Rites. In January 2011 Justin Patterson, a 22-year-old black man whom Keyke described as her “first love,” was shot dead by Norman Neesmith, a 64-year-old white man whose adopted daughter, Danielle, had invited Patterson into his home without his knowing. The case, which received scarce media attention, began with seven charges against Neesmith, including murder, but ended in a plea bargain.

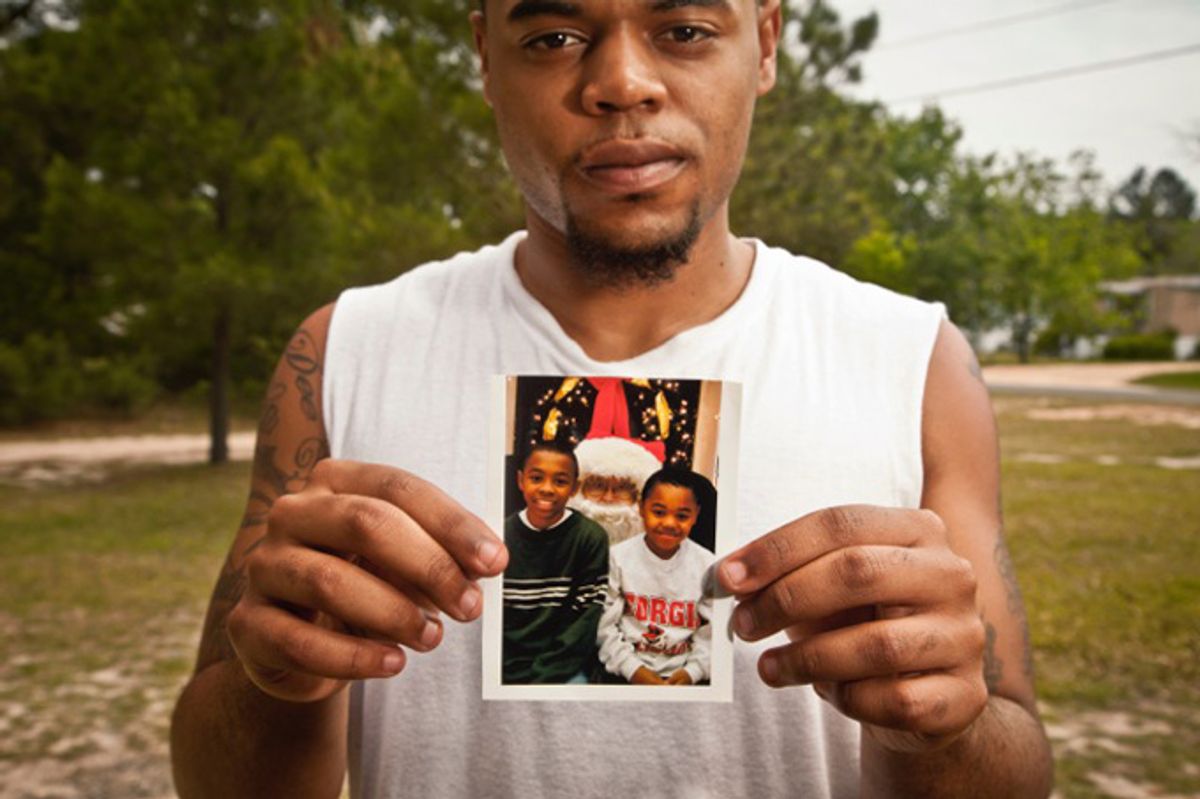

Niesha Bell, the black prom queen of 2009, said that Montgomery County was taking one step forward and two steps back with the integration of the prom followed by Patterson’s killing. Patterson’s death divided the community once again. Many people were firmly convinced that it was a racially motivated murder, while others thought that what Neesmith did was justified. For me, it was very difficult to be in court for this case. It seemed as if the Pattersons were invisible to most of the room, and the district attorney was not representing them. The family certainly did not believe that justice was served, and much of the community was devastated, if unsurprised. Justin’s father, Julius Patterson, complained that his son was the one put on trial, not Neesmith. Then there were those in the community, including Neesmith’s lawyer, who thought the mere fact that a white man was held accountable for a black man’s death was progress enough.

Today there are many signs that we are finally waking up to the depths of racial prejudice, despite the seemingly endless bad news. Since Trayvon Martin’s death, and especially in the past year, the media have thankfully been paying more attention to the many stories of unarmed African Americans shot dead—whether it’s because our consciousness is changing or because people have camera phones to record what’s long been happening. I believe it’s a mixture of both. When Justin Patterson was killed and it wasn’t reported, that was part of a pattern of ignoring a massive, persistent problem. I believe that we are breaking this pattern, thanks in part to new technologies but especially thanks to committed activists and everyday people who are raising awareness of racial injustice.

Making change at the local level matters. I learned about Montgomery County’s segregated proms because of one brave high school student. Many students and their parents were afraid to talk to me because, they said, keeping their mouths shut meant keeping their friends, their jobs, their livelihoods. But in 2000 Anna Rich, a student at Montgomery County High School, risked all that when she couldn’t take her boyfriend to the prom because he was black and she was white. A subscriber to SPIN magazine, Rich wrote a letter to the editor asking that someone cover what was happening in her town—and that’s how I was first commissioned to follow this story. People wouldn’t know that segregated proms still existed in the United States in the 21st century if Anna Rich hadn’t written that letter. All it took was one courageous teenager to change the course of an entire community. That gives me so much hope that the next generation will continue to make real progress, even as it pains us to hear of the racial injustice unfolding all around us. It is important to hold on to that optimism, as this next generation knows. Earlier this month, several students from Montgomery County High School sent me pictures of their most recent prom king and queen, a mixed couple, with a short note: See it’s really happening.

Shares