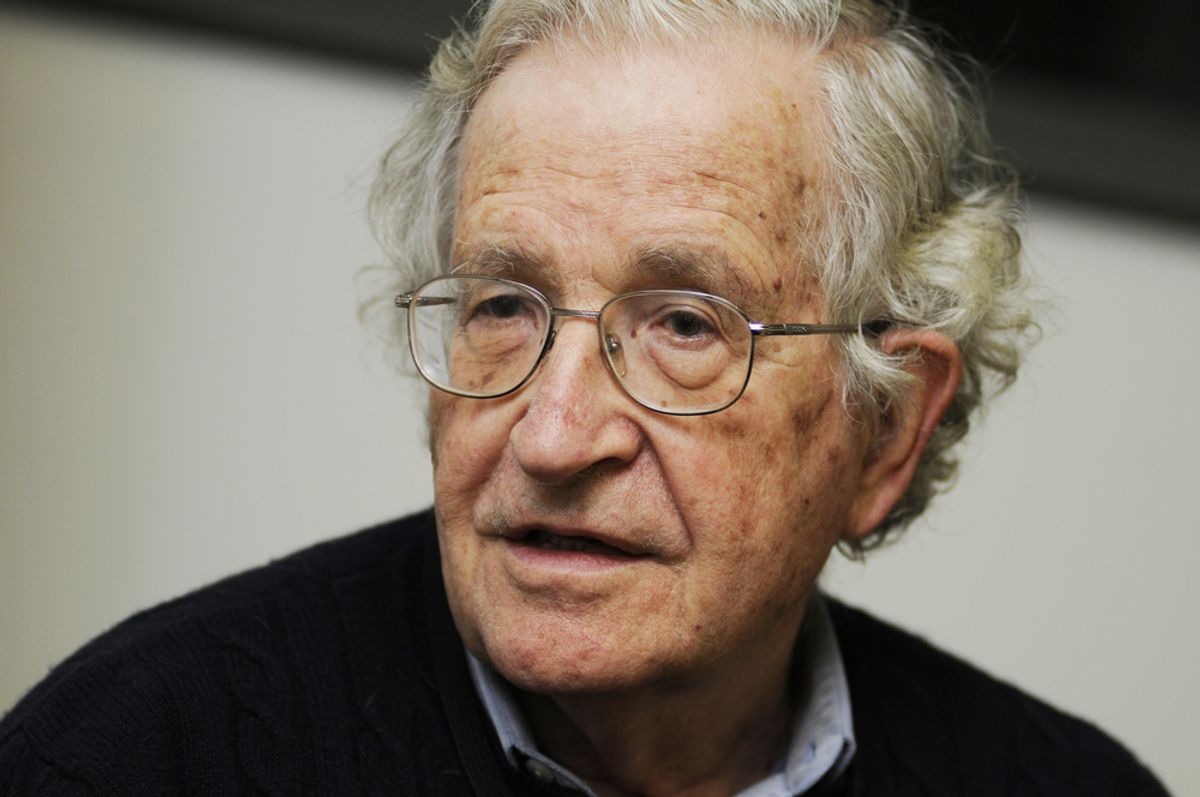

Noam Chomsky, to rehearse a cliché, is among the world’s greatest living radical intellectuals. It is no less trite or true to add that he is also a broadly controversial figure: accused from various corners of a variety of failings ranging from “genocide denial” to rigid, “amoral quietism” in the face of mass atrocities. Most recently, critics of dissimilar political hues claim to have identified a range of follies in his statements on Syria.

Noam Chomsky, to rehearse a cliché, is among the world’s greatest living radical intellectuals. It is no less trite or true to add that he is also a broadly controversial figure: accused from various corners of a variety of failings ranging from “genocide denial” to rigid, “amoral quietism” in the face of mass atrocities. Most recently, critics of dissimilar political hues claim to have identified a range of follies in his statements on Syria.

In the following interview, freelance journalist Emanuel Stoakes puts some of these criticisms to Chomsky.

While reasserting his opposition to full-scale military intervention, Chomsky says he does not in principle oppose the idea of a no-fly zone established alongside a humanitarian corridor (though Putin’s recent interventions have all but killed the possibility of the former option). Chomsky also clarifies his positions on the 1995 Srebrenica massacre and NATO’s 1999 intervention in Kosovo.

In addition to answering his critics, Chomsky gives his thoughts on a wide range of other topics: what should be done to combat ISIS, the significance of popular struggles in South America, and the future of socialism.

As always, his underlying belief in our capacity to build a better society shines through.

What’s your reaction to the attacks in Paris earlier this month, and what do you think of the current Western strategy of bombing ISIS?

The current strategy plainly is not working. The ISIS statements, both for this and the Russian airliner, were very explicit: you bomb us and you will suffer. They are a monstrosity, and these are terrible crimes, but it doesn’t help to hide our heads in the sand.

The best outcome would be if ISIS were destroyed by local forces, which could happen, but it will require that Turkey agree. And the outcome could be just as bad if the jihadi elements supported by Turkey, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia are the victors.

The optimal outcome would be a negotiated settlement of the kind being inched towards in Vienna, combined with the above. Long shots.

Like it or not, ISIS seems to have established itself pretty firmly in Sunni areas of Iraq and Syria. They seem to be engaged in a process of state building that is extremely brutal but fairly successful, and attracts the support of Sunni communities who may despise ISIS but see it as the only defense against alternatives that are even worse. The one major regional power that is opposing it is Iran, but the Iran-backed Shiite militias are reputed to be as brutal as ISIS and probably mobilize support for ISIS.

The sectarian conflicts that are tearing the region to shreds are substantially a consequence of the Iraq invasion. That’s what Middle East specialist Graham Fuller, a former CIA analyst, means when he says that “I think the United States is one of the key creators of this organization.”

Destruction of ISIS by any means that can be imagined might lay the basis for something worse, as has been happening quite regularly with military intervention. The state system in the region imposed by French and British imperial might after World War I, with little concern for the populations under their control, is unraveling.

The future looks bleak, though there are some patches of light, as in the Kurdish areas. Steps can be taken to reduce many of the tensions in the region and to constrain and reduce the outlandishly high level of armament, but it is not clear what more outside powers can do apart from fanning the flames, as they have been doing for years.

Earlier this year, we saw the Greek government struggling with its creditors to work out a deal. It’s tempting to view this showdown, as well as the crisis as a whole, as less a case of the EU trying to manage a debt crisis in the common interests of the union and more as a battle between Greek society and those who benefit from austerity. Would you agree? How do you view the situation?

There has been no serious effort to manage a debt crisis. The policies imposed on Greece by the troika sharply exacerbated the crisis by undermining the economy and blocking hopeful chances for growth. The debt-to-GDP ratio is now far higher than it was before these policies were instituted, and there’s been a terrible toll on the people of Greece — though the German and French banks that bear a large part of responsibility for the crisis are doing fine.

The so-called “bailouts” for Greece mostly went into the pockets of the creditors, as much as 90 percent by some estimates. Former Bundesbank chief Karl Otto Pöhl observed very plausibly that the whole affair “was about protecting German banks, but especially the French banks, from debt write-offs.”

Commenting in the leading US establishment journal Foreign Affairs, Mark Blyth, one of the most cogent critics of the destructive austerity-under-depression programs, writes, “We’ve never understood Greece because we have refused to see the crisis for what it was — a continuation of a series of bailouts for the financial sector that started in 2008 and that rumbles on today.”

It is recognized on all sides that the debt cannot be paid. It should have been radically restructured long ago, when the crisis could have easily been managed, or simply declared “odious” and cancelled.

The ugly face of contemporary Europe is presented by German Finance Minister Schäuble, apparently the most popular political figure in Germany. As reported by Reuters news service, he explained that “a write-off of some of Europe’s loans to Greece might be needed to get the country’s debt to a manageable level,” while he “in the same breath ruled out such a step.” In brief, we’ve milked you about as dry as we can, so get lost. And much of the population is literally getting lost, with hopes for decent survival smashed.

Actually Greeks are not yet quite milked dry. The shameful settlement imposed by the banks and bureaucracy includes measures to ensure that Greek assets will be taken over by the right greedy hands.

Germany’s role is particularly shameful, not just because Nazi Germany devastated Greece, but also because, as Thomas Pikettypointed out in Die Zeit, “Germany is really the single best example of a country that, throughout its history, has never repaid its external debt. Neither after the First nor the Second World War.”

The London Agreement of 1953 wiped out over half of Germany’s debt, laying the basis for its economic recovery, and currently, Piketty added, far from being “generous,” these days “Germany is profiting from Greece as it extends loans at comparatively high interest rates.” The whole business is sordid.

The policies of austerity that have been imposed on Greece (and on Europe generally) were always absurd from an economic point of view, and have been a complete disaster for Greece. As weapons of class war, however, they have been rather effective in undermining welfare systems, enriching the northern banks and the investor class, and driving democracy to the margins.

The behavior of the troika today is a disgrace. One can scarcely doubt that their goal is to establish firmly the principle that the masters must be obeyed: defiance of the northern banks and the Brussels bureaucracy will not be tolerated, and thoughts of democracy and popular will in Europe must be abandoned.

Do you think the struggle taking place over Greece’s future is representative of a lot of what is happening in the world at the moment — i.e., a struggle between the needs of society and the demands of capitalism? If so, do you see much hope for decent human outcomes when the trump cards all seem to be held by a small number of people linked to private power?

In Greece, and in Europe more generally in varying degrees, some of the most admirable achievements of the postwar years are being reversed under a destructive version of the neoliberal assault on the global population of the past generation.

But it can be reversed. Among the most obedient students of the neoliberal orthodoxy were the countries of Latin America, and not surprisingly, they were also among those who suffered the worst harm. But in recent years they have led the way towards rejecting the orthodoxy, and more generally, for the first time in five hundred years are taking significant steps towards unification, freeing themselves from imperial (in the past century US) domination, and confronting the shocking internal problems of potentially rich societies that had been traditionally governed by wealthy foreign-oriented (mostly white) elites in a sea of misery.

Syriza in Greece might have signaled a similar development, which is why it had to be smashed so savagely. There are other reactions in Europe and elsewhere that could turn the tide and lead to a much better future.

The twentieth anniversary of the Srebrenica massacre passed this year. It has emerged that the US watched the killing take place in real time from satellites, and that many of the world’s great powers were negligent or worse when it came to making efforts to prevent predictable slaughter there. What do you think should have been done at the time? Do you think, for example, that the Bosnian Muslims should have been given a greater chance to defend themselves far earlier, for example?

Srebrenica was a barely protected safe area — and we should not forget that thanks to that status, it was as a base for Nasir Oric’s murderous Bosnian militias to attack surrounding Serb villages, taking a brutal toll and boasting of the achievement. That there would sooner or later be a Serb response was not too surprising, and measures should have been taken to “prevent predictable slaughter,” to borrow your words.

The best approach, which might have been feasible, would have been to reduce and maybe end the hostilities in the region rather than allowing them to escalate.

You’ve come in for a lot of criticism for your position on the Kosovo intervention. My (perhaps mistaken) understanding is that you believe there were alternatives to the bombing, and that the violence could have been stopped if there had been greater political will to find a diplomatic solution. Is that right? Can you outline what could have been done as an alternative?

I haven’t seen criticisms of my position on the intervention, and there are unlikely to be any, for the simple reason that I scarcely took a position. As I made explicit in what I wrote on the topic (The New Military Humanism), I hardly even discussed the propriety of the NATO intervention. That’s clearly stated in the early pages.

The topic is indeed brought up, three pages from the end, noting that what precedes — the entire book — leaves the question of what should have been done in Kosovo “unanswered,” though it seems a “reasonable judgment” that the US was selecting one of the more harmful of several options available.

As explained clearly and unambiguously from the outset, even from the title, the book is about a wholly different topic: the import of the Kosovo events for the “new era” of “principles and values” led by the “enlightened states” whose foreign policy has entered a “noble phase” with a “saintly glow” (to quote some of the celebratory rhetoric reviewed).

That very important topics must be sharply distinguished from the question of what should have been done, which I scarcely addressed. An important topic, and evidently an unpopular one, best avoided. I don’t recall even seeing a mention of the subject of the entire book in the critical commentary on it.

I did review the diplomatic options available, pointing out that the settlement after seventy-eight days of bombing was a compromise between the NATO and Serbian pre-bombing positions.

A year later, after the war ended, in my book A New Generation Draws the Line, I reviewed in extensive detail the rich Western documentary record on the immediate background to the bombing. It reveals that there was a steady level of violence divided between KLA guerrillas attacking from Albania and a brutal Serb response, and that the atrocities were very sharply escalated after the bombing, exactly as was predicted publicly, and to US authorities privately, by commanding Gen. Mark Clark.

If there has been criticism of what I actually wrote, I haven’t seen it, though you’re right that there has been a great deal of furious condemnation — namely, of what I didn’t write.

As to a possible alternative, there were what seemed to be fairly promising diplomatic options. Whether they could have worked, we don’t know, since they were ignored in favor of bombing.

The usual interpretation, which I’ve reviewed elsewhere, is that the bombing was motivated by a sharp upsurge of atrocities. This reversal of the chronology is quite standard, and useful to establish the legitimacy of NATO violence. The upsurge of atrocities was the consequence of the bombing, not its cause — and as noted, was predicted quite publicly and authoritatively.

What do you think was the real objective of NATO’s Balkan intervention?

If we can believe the US-UK leadership, the real objective was to establish the “credibility of NATO” (there were other pretexts, but they quickly collapse). As Tony Blair summarized the official reason, failure to bomb “would have dealt a devastating blow to the credibility of NATO,” and “the world would have been less safe as a result of that” — though, as I reviewed in some detail, the “world” overwhelmingly disagreed, often very sharply.

“Establishing credibility” — basically, the Mafia principle — is a significant feature of great power policy. A deeper look suggests motives beyond those officially stressed.

Do you oppose military intervention under any circumstances during dire humanitarian disasters? What are the conditions that would make it acceptable from your point of view?

Pure pacifists would always oppose military intervention. I am not one, but I think that like any resort to violence, it carries a heavy burden of proof. It’s impossible to give a general answer as to when it is justified, apart from some useless formulas.

It is not easy to find genuine cases where intervention has been justified. I’ve reviewed the historical and scholarly record. It’s very thin. Two possible examples stand out in the post–World War II period: the Vietnamese invasion of Cambodia, terminating Khmer Rouge crimes as they were peaking; and the Indian invasion of Pakistan that ended the hideous atrocities in the former East Pakistan.

These two cases do not enter the standard canon, however, because of the fallacy of “wrong agency” and because they were both bitterly opposed by Washington, which reacted in quite ugly ways.

Moving on to Syria, we see an appalling humanitarian situation and no end in sight in terms of the internecine warfare taking place. I know some Syrian activists who are furious at what they perceive to be your tolerance of the immense misery being experienced by people living with barrel bombs and so on; they say this because they think you are opposed to any kind of intervention against Assad, however limited, on ideological grounds.

Is this accurate or fair? Would you support the idea of a no-fly zone, with an enforced humanitarian corridor? Can you clarify your position on Syria?

If intervention against Assad would mitigate or end the appalling situation, it would be justified. But would it? Intervention is not advocated by careful observers on the scene with close knowledge of Syria and the current situation — Patrick Cockburn, Charles Glass, quite a few others who are bitter critics of Assad. They warn, with no little plausibility I think, that it might well exacerbate the crisis.

The record of military intervention in the region has been awful with very rare exceptions, a fact that can hardly be overlooked. No-fly zones, humanitarian corridors, support for the Kurds, and some other measures would be likely to be helpful. But while it is easy to call for military intervention, it is no simple matter to provide reasoned and well-thought-out plans, taking into account likely consequences. I haven’t seen any.

One can imagine a world in which intervention is undertaken by some benign force dedicated to the interests of people who are suffering. But if we care about victims, we cannot make proposals for imaginary worlds. Only for this world, in which intervention, with rare consistency, is undertaken by powers dedicated to their own interests, where the victims and their fate is incidental, despite lofty professions.

The historical record is painfully clear, and there have been no miraculous conversions. That does not mean that intervention can never be justified, but these considerations cannot be ignored — at least, if we care about the victims.

Looking back at your long life of activism and scholarship, what cause or issue are you most glad to have supported? Conversely, what are your greatest regrets — do you wish that you had done more on certain fronts?

I can’t really say. There are many that I’m glad to have supported, to a greater or lesser degree. The cause that I pursued most intensely, from the early 1960s, was the US wars in Indochina, the most severe international crime in the post–World War II era. That included speaking, writing, organizing, demonstrations, civil disobedience, direct resistance, and the expectation, barely averted more or less by accident, of a possible long prison sentence.

Some other engagements were similar, but not at that level of intensity. And each case has regrets, always the same ones: too little, too late, too ineffective, even when there were some real achievements of the dedicated struggles of many people in which I was privileged to be able to participate in some way.

What gives you the most hope about the future? Do you feel that young people in the US that you have interacted with are different from some of those you dealt with decades before? Have social attitudes changed for the better?

Hopes for the future are always about the same: courageous people, often under severe duress, refusing to bow to illegitimate authority and persecution, others devoting themselves to support and to combatting injustice and violence, young people who sincerely want to change the world. And the record of successes, always limited, sometimes reversed, but over time bending the arc of history towards justice, to borrow the words that Martin Luther King made famous in word and deed.

How do you view the future of socialism? Are you inspired by developments in South America? Are there lessons for the Left in North America?

Like other terms of political discourse, “socialism” can mean many different things. I think one can trace an intellectual and practical trajectory from the Enlightenment to classical liberalism, and (after its wreckage on the shoals of capitalism, in Rudolf Rocker’s evocative phrase) on to the libertarian version of socialism that converges with leading anarchist tendencies.

My feeling is that the basic ideas of this tradition are never far below the surface, rather like Marx’s old mole, always about to break through when the right circumstances arise, and the right flames are lit by engaged activists.

What has taken place in recent years in South America is of historic significance, I think. For the first time since the conquistadors, the societies have taken steps of the kind I outlined earlier. Halting steps, but very significant ones.

The basic lesson is that if this can be achieved under harsh and brutal circumstances, we should be able to do much better enjoying a legacy of relative freedom and prosperity, thanks to the struggles of those who came before us.

Do you agree with Marx’s prognosis that capitalism will eventually destroy itself? Do you think that an alternative way of life and system of economics can take hold before such an implosion occurs, with potentially chaotic consequences? What should ordinary people concerned with the survival of their family, and that of the world, do?

Marx studied an abstract system that has some of the central features of really-existing capitalism, but not others, including the crucial state role in development and in sustaining predatory institutions. Like much of the financial sector, which in the US depends for most of its profits on the implicit government insurance program, according to a recent IMF study — over $80 billion, a year according to the business press.

Large-scale state intervention has been a leading feature of the developed societies from England to the US to Europe and to Japan and its former colonies, up to the present moment. The technology that we are now using, to take one example. Many mechanisms have been developed that might preserve existing forms of state capitalism.

The existing system may well destroy itself for different reasons, which Marx also discussed. We are now heading, eyes open, towards an environmental catastrophe that might end the human experiment just as it is wiping out species at a rate not seen since 65 million years ago when a huge asteroid hit the earth – and now we are the asteroid.

There is more than enough for “ordinary people” (and we’re all ordinary people) to do to fend off disasters that are not remote and to construct a far more free and just society.

Shares